(Press-News.org) This press release is available in German.

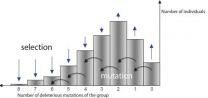

From protozoans to mammals, evolution has created more and more complex structures and better-adapted organisms. This is all the more astonishing as most genetic mutations are deleterious. Especially in small asexual populations that do not recombine their genes, unfavourable mutations can accumulate. This process is known as Muller's ratchet in evolutionary biology. The ratchet, proposed by the American geneticist Hermann Joseph Muller, predicts that the genome deteriorates irreversibly, leaving populations on a one-way street to extinction. In collaboration with colleagues from the US, Richard Neher from the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology has shown mathematically how Muller's ratchet operates and he has investigated why populations are not inevitably doomed to extinction despite the continuous influx of deleterious mutations.

The great majority of mutations are deleterious. "Due to selection individuals with more favourable genes reproduce more successfully and deleterious mutations disappear again," explains the population geneticist Richard Neher, leader of an independent Max Planck research group at the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen, Germany. However, in small populations such as an asexually reproducing virus early during infection, the situation is not so clear-cut. "It can then happen by chance, by stochastic processes alone, that deleterious mutations in the viruses accumulate and the mutation-free group of individuals goes extinct," says Richard Neher. This is known as a click of Muller's ratchet, which is irreversible – at least in Muller's model.

Muller published his model on the evolutionary significance of deleterious mutations in 1964. Yet to date a quantitative understanding of the ratchet's processes was lacking. Richard Neher and Boris Shraiman from the University of California in Santa Barbara have now published a new theoretical study on Muller's ratchet. They chose a comparably simple model with only deleterious mutations all having the same effect on fitness. The scientists assumed selection against those mutations and analysed how fluctuations in the group of the fittest individuals affected the less fit ones and the whole population. Richard Neher and Boris Shraiman discovered that the key to the understanding of Muller's ratchet lies in a slow response: If the number of the fittest individuals is reduced, the mean fitness decreases only after a delay. "This delayed feedback accelerates Muller's ratchet," Richard Neher comments on the results. It clicks more and more frequently.

"Our results are valid for a broad range of conditions and parameter values – for a population of viruses as well as a population of tigers." However, he does not expect to find the model's conditions one-to-one in nature. "Models are made to understand the essential aspects, to identify the critical processes," he explains.

In a second study Richard Neher, Boris Shraiman and several other US-scientists from the University of California in Santa Barbara and Harvard University in Cambridge investigated how a small asexual population could escape Muller's ratchet. "Such a population can only stay in a steady state for a long time when beneficial mutations continually compensate for the negative ones that accumulate via Muller's ratchet," says Richard Neher. For their model the scientists assumed a steady environment and suggest that there can be a mutation-selection balance in every population. They have calculated the rate of favourable mutations required to maintain the balance. The result was surprising: Even under unfavourable conditions, a comparably small proportion in the range of several percent of positive mutations is sufficient to sustain a population.

These findings could explain the long-term maintenance of mitochondria, the so-called power plants of the cell that have their own genome and divide asexually. By and large, evolution is driven by random events or as Richard Neher says: "Evolutionary dynamics are very stochastic."

INFORMATION:

Original publications:

Richard A. Neher, Boris I. Shraiman: Fluctuations of fitness distributions and the rate of Muller's ratchet. Genetics, Vol. 191, pp. 1283-1293, August 2012. doi:10.1534/genetics.112.141325

Sidhartha Goyal, Daniel J. Balick, Elizabeth R. Jerison, Richard A. Neher, Boris I. Shraiman and Michael M. Desai: Dynamic Mutation-Selection Balance as an Evolutionary Attractor. Genetics, Vol. 191, August 2012. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.141291

Populations survive despite many deleterious mutations

Max Planck scientist investigates the evolutionary model of Muller's ratchet

2012-08-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New approach of resistant tuberculosis

2012-08-10

Scientists of the Antwerp Institute of Tropical Medicine have breathed new life into a forgotten technique and so succeeded in detecting resistant tuberculosis in circumstances where so far this was hardly feasible. Tuberculosis bacilli that have become resistant against our major antibiotics are a serious threat to world health.

If we do not take efficient and fast action, 'multiresistant tuberculosis' may become a worldwide epidemic, wiping out all medical achievements of the last decades.

A century ago tuberculosis was a lugubrious word, more terrifying than 'cancer' ...

How much nitrogen is fixed in the ocean?

2012-08-10

Of course scientists like it when the results of measurements fit with each other. However, when they carry out measurements in nature and compare their values, the results are rarely "smooth". A contemporary example is the ocean's nitrogen budget. Here, the question is: how much nitrogen is being fixed in the ocean and how much is released? "The answer to this question is important to predicting future climate development. All organisms need fixed nitrogen in order to build genetic material and biomass", explains Professor Julie LaRoche from the GEOMAR | Helmholtz Centre ...

Stem cells may prevent post-injury arthritis

2012-08-10

DURHAM, N.C.-- Duke researchers may have found a promising stem cell therapy for preventing osteoarthritis after a joint injury.

Injuring a joint greatly raises the odds of getting a form of osteoarthritis called post-traumatic arthritis, or PTA. There are no therapies yet that modify or slow the progression of arthritis after injury.

Researchers at Duke University Health System have found a very promising therapeutic approach to PTA using a type of stem cell, called mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), in mice with fractures that typically would lead to them developing ...

Autonomous robotic plane flies indoors

2012-08-10

CAMBRDIGE, Mass. — For decades, academic and industry researchers have been working on control algorithms for autonomous helicopters — robotic helicopters that pilot themselves, rather than requiring remote human guidance. Dozens of research teams have competed in a series of autonomous-helicopter challenges posed by the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI); progress has been so rapid that the last two challenges have involved indoor navigation without the use of GPS.

But MIT's Robust Robotics Group — which fielded the team that won the last ...

Good news: Migraines hurt your head but not your brain

2012-08-10

Boston, MA—Migraines currently affect about 20 percent of the female population, and while these headaches are common, there are many unanswered questions surrounding this complex disease. Previous studies have linked this disorder to an increased risk of stroke and structural brain lesions, but it has remained unclear whether migraines had other negative consequences such as dementia or cognitive decline. According to new research from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH), migraines are not associated with cognitive decline.

This study is published online by the British ...

New regulatory mechanism discovered in cell system for eliminating unneeded proteins

2012-08-10

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – August 10, 2012) A faulty gene linked to a rare blood vessel disorder has led investigators to discover a mechanism involved in determining the fate of possibly thousands of proteins working inside cells.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital scientists directed the study, which provides insight into one of the body's most important regulatory systems, the ubiquitin system. Cells use it to get rid of unneeded proteins. Problems in this system have been tied to cancers, infections and other diseases. The work appears in today's print edition of the journal ...

Why do organisms build tissues they seemingly never use?

2012-08-10

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Why, after millions of years of evolution, do organisms build structures that seemingly serve no purpose?

A study conducted at Michigan State University and published in the current issue of The American Naturalist investigates the evolutionary reasons why organisms go through developmental stages that appear unnecessary.

"Many animals build tissues and structures they don't appear to use, and then they disappear," said Jeff Clune, lead author and former doctoral student at MSU's BEACON Center of Evolution in Action. "It's comparable to building ...

Individualized care best for lymphedema patients, MU researcher says

2012-08-10

COLUMBIA, Mo. – Millions of American cancer survivors experience chronic discomfort as a result of lymphedema, a common side effect of surgery and radiation therapy in which affected areas swell due to protein-rich fluid buildup. After reviewing published literature on lymphedema treatments, a University of Missouri researcher says emphasizing patients' quality of life rather than focusing solely on reducing swelling is critical to effectively managing the condition.

Jane Armer, professor in the MU Sinclair School of Nursing and director of nursing research at Ellis Fischel ...

Spending more on trauma care doesn't translate to higher survival rates

2012-08-10

A large-scale review of national patient records reveals that although survival rates are the same, the cost of treating trauma patients in the western United States is 33 percent higher than the bill for treating similarly injured patients in the Northeast. Overall, treatment costs were lower in the Northeast than anywhere in the United States.

The findings by Johns Hopkins researchers, published in The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, suggest that skyrocketing health care costs could be reined in if analysts focus on how caregivers in lower-cost regions manage ...

Stabilizing shell effects in heaviest elements directly measured

2012-08-10

This press release is available in German.

So-called "superheavy" elements owe their very existence exclusively to shell effects within the atomic nucleus. Without this stabilization they would disintegrate in a split second due to the strong repulsion between their many protons. The constituents of an atomic nucleus, the protons and neutrons, organize themselves in shells. Certain "magic" configurations with completely filled shells render the protons and neutrons to be more strongly bound together.

Long-standing theoretical predictions suggest that also in superheavy ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Wildfire smoke linked to rise in violent assaults, new 11-year study finds

New technology could use sunlight to break down ‘forever chemicals’

Green hydrogen without forever chemicals and iridium

Billion-DKK grant for research in green transformation of the built environment

For solar power to truly provide affordable energy access, we need to deploy it better

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

[Press-News.org] Populations survive despite many deleterious mutationsMax Planck scientist investigates the evolutionary model of Muller's ratchet