(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA -- The simple act of picking up a pencil requires the coordination of dozens of muscles: The eyes and head must turn toward the object as the hand reaches forward and the fingers grasp it. To make this job more manageable, the brain's motor cortex has implemented a system of shortcuts. Instead of controlling each muscle independently, the cortex is believed to activate muscles in groups, known as "muscle synergies." These synergies can be combined in different ways to achieve a wide range of movements.

A new study from MIT, Harvard Medical School and the San Camillo Hospital in Venice finds that after a stroke, these muscle synergies are activated in altered ways. Furthermore, those disruptions follow specific patterns depending on the severity of the stroke and the amount of time that has passed since the stroke.

The findings, published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could lead to improved rehabilitation for stroke patients, as well as a better understanding of how the motor cortex coordinates movements, says Emilio Bizzi, an Institute Professor at MIT and senior author of the paper.

"The cortex is responsible for motor learning and for controlling movement, so we want to understand what's going on there," says Bizzi, who is a member of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT. "How does the cortex translate an idea to move into a series of commands to accomplish a task?"

Coordinated control

One way to explore motor cortical functions is to study how motor patterns are disrupted in stroke patients who suffered damage to the motor areas.

In 2009, Bizzi and his colleagues first identified muscle synergies in the arms of people who had suffered mild strokes by measuring electrical activity in each muscle as the patients moved. Then, by utilizing a specially designed factorization algorithm, the researchers identified characteristic muscle synergies in both the stroke-affected and unaffected arms.

"To control, precisely, each muscle needed for the task would be very hard. What we have proven is that the central nervous system, when it programs the movement, makes use of these modules," Bizzi says. "Instead of activating simultaneously 50 muscles for a single action, you will combine a few synergies to achieve that goal."

In the 2009 study, and again in the new paper, the researchers showed that synergies in the affected arms of patients who suffered mild strokes in the cortex are very similar to those seen in their unaffected arms even though the muscle activation patterns are different. This shows that muscle synergies are structured within the spinal cord, and that cortical stroke alters the ability of the brain to activate these synergies in the appropriate combinations.

However, the new study found a much different pattern in patients who suffered more severe strokes. In those patients, synergies in the affected arm merged to form a smaller number of larger synergies. And in a third group of patients, who had suffered their stroke many years earlier, the muscle synergies of the affected arm split into fragments of the synergies seen in the unaffected arm.

This phenomenon, known as fractionation, does not restore the synergies to what they would have looked like before the stroke. "These fractionations appear to be something totally new," says Vincent Cheung, a research scientist at the McGovern Institute and lead author of the new PNAS paper. "The conjecture would be that these fragments could be a way that the nervous system tries to adapt to the injury, but we have to do further studies to confirm that."

Toward better rehabilitation

The researchers believe that these patterns of synergies, which are determined by both the severity of the deficit and the time since the stroke occurred, could be used as markers to more fully describe individual patients' impaired status. "In some of the patients, we see a mixture of these patterns. So you can have severe but chronic patients, for instance, who show both merging and fractionation," Cheung says.

The findings could also help doctors design better rehabilitation programs. The MIT team is now working with several hospitals to establish new therapeutic protocols based on the discovered markers.

About 700,000 people suffer strokes in the United States every year, and many different rehabilitation programs exist to treat them. Choosing one is currently more of an art than a science, Bizzi says. "There is a great deal of need to sharpen current procedures for rehabilitation by turning to principles derived from the most advanced brain research," he says. "It is very likely that different strategies of rehabilitation will have to be used in patients who have one type of marker versus another."

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Italian Ministry of Health.

Written by Anne Trafton, MIT News Office

END

Nanoparticles tailored to latch onto blood platelets rapidly create healthy clots and nearly double the survival rate in the vital first hour after injury, new research shows.

"We knew an injection of these nanoparticles stopped bleeding faster, but now we know the bleeding is stopped in time to increase survival following trauma," said Erin Lavik, a professor of biomedical engineering at Case Western Reserve University and leader of the effort.

The researchers are developing synthetic platelets that first responders and battlefield medics could carry with them to stabilize ...

The risk of dying from breast cancer was not related to high mammographic breast density in breast cancer patients, according to a study published August 20 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

One of the strongest risk factors for non-familial breast cancer is elevated mammographic breast density. While women with elevated mammographic breast density have a higher risk of developing breast cancer, it is not established whether a higher density indicates a lower chance of survival in breast cancer patients.

In order to determine if higher mammographic breast ...

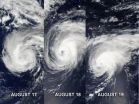

NASA's Terra and Aqua satellite have captured Hurricane Gordon over three days as it neared the Azores Islands in the eastern Atlantic Ocean. Gordon weakened to a tropical storm on August 20.

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, or MODIS, is an instrument that flies onboard NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites and provides high-resolution imagery to users. When NASA's Terra satellite flew over Gordon on August 17 at 9:30 a.m. EDT it was a tropical storm and did not have a visible eye. It was followed up by a fly over of NASA's Aqua satellite on August 18 at ...

The first evidence of a planet's destruction by its aging star has been discovered by an international team of astronomers. The evidence indicates that the missing planet was devoured as the star began expanding into a "red giant" -- the stellar equivalent of advanced age. "A similar fate may await the inner planets in our solar system, when the Sun becomes a red giant and expands all the way out to Earth's orbit some five-billion years from now," said Alexander Wolszczan, Evan Pugh Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics at Penn State University, who is one of the members ...

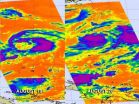

Tropical Storm Bolaven was born over the weekend of August 18-19 in the western North Pacific, and NASA captured infrared satellite imagery of its birth and growth.

NASA's Aqua satellite has been monitoring the birth and progress of Tropical Storm Bolaven in the western North Pacific from Aug 19-20, 2012. The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument has provided infrared satellite imagery that shows the development of colder thunderstorm cloud-top temperatures, that were indicative of strengthening storms. Tropical Storm Bolaven also took more of a rounded shape ...

Researchers have long studied infants' perceptions of safe and risky ground by observing their willingness to cross a visual cliff, a large drop-off covered with a solid glass surface. In crawling, infants grow more likely to avoid the apparent drop-off, leading researchers to conclude that they have a fear of heights. Now a new study has found that although infants learn to avoid the drop-off while crawling, this knowledge doesn't transfer to walking. This suggests that what infants learn is to perceive the limits of their ability to crawl or walk, not a generalized fear ...

Ethnic and political violence in the Middle East can increase violence in families, schools, and communities, which can in turn boost children's aggressiveness, especially among 8-year-olds. Those are the findings of a new study that examined children and their parents in the Middle East.

"The study has important implications for understanding how political struggles can spill over into the everyday lives of families and children, and suggests that intervention might be necessary in a number of different social areas to protect children from the adverse impacts of exposure ...

Young children in lower-income families who live in high-cost areas don't do as well academically as their counterparts in low-cost areas, according to a new study.

The study, by researchers at Child Trends and the University of California (UCLA), appears in the journal Child Development.

"Among families with incomes below 300 percent of the federal poverty threshold—that's below $66,339 for a family of four—living in a region with a higher cost of living was related to lower academic achievement in first grade," according to Nina Chien, a research scientist with Child ...

Regardless of how much a high school student generally studies each day, if that student sacrifices sleep in order to study more than usual, he or she is more likely to have academic problems the following day. Because students tend to increasingly sacrifice sleep time for studying in the latter years of high school, this negative dynamic becomes more and more prevalent over time.

Those are the findings of a new longitudinal study that focused on daily and yearly variations of students who sacrifice sleep to study. The research was conducted at the University of California, ...

It's thought that children grow increasingly distant and independent from their parents during their teen years. But a new longitudinal study has found that spending time with parents is important to teens' well-being.

The study, conducted at the Pennsylvania State University, appears in the journal Child Development.

Researchers studied whether the stereotype of teens growing apart from their parents and spending less time with them captured the everyday experiences of families by examining changes in the amount of time youths spent with their parents from early to ...