(Press-News.org) Turning the volume up too high on your headphones can damage the coating of nerve cells, leading to temporary deafness; scientists from the University of Leicester have shown for the first time.

Earphones or headphones on personal music players can reach noise levels similar to those of jet engines, the researchers said.

Noises louder than 110 decibels are known to cause hearing problems such as temporary deafness and tinnitus (ringing in the ears), but the University of Leicester study is the first time the underlying cell damage has been observed.

The study has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

University of Leicester researcher Dr Martine Hamann of the Department of Cell Physiology and Pharmacology, who led the study, said:

"The research allows us to understand the pathway from exposure to loud noises to hearing loss. Dissecting the cellular mechanisms underlying this condition is likely to bring a very significant healthcare benefit to a wide population. The work will help prevention as well as progression into finding appropriate cures for hearing loss."

Nerve cells that carry electrical signals from the ears to the brain have a coating called the myelin sheath, which helps the electrical signals travel along the cell. Exposure to loud noises - i.e. noise over 110 decibels - can strip the cells of this coating, disrupting the electrical signals. This means the nerves can no longer efficiently transmit information from the ears to the brain.

However, the coating surrounding the nerve cells can reform, letting the cells function again as normal. This means hearing loss can be temporary, and full hearing can return, the researchers said.

Dr Hamann explained: "We now understand why hearing loss can be reversible in certain cases. We showed that the sheath around the auditory nerve is lost in about half of the cells we looked at, a bit like stripping the electrical cable linking an amplifier to the loudspeaker. The effect is reversible and after three months, hearing has recovered and so has the sheath around the auditory nerve."

The findings are part of ongoing research into the effects of loud noises on a part of the brain called the dorsal cochlear nucleus, the relay that carries signals from nerve cells in the ear to the parts of the brain that decode and make sense of sounds. The team has already shown that damage to cells in this area can cause tinnitus - the sensation of 'phantom sounds' such as buzzing or ringing.

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the Wellcome Trust, Medisearch, GlaxoSmithkline and the Royal Society.

Notes for editors:

For more information contact: Martine Hamann, email: mh86@le.ac.uk

PNAS reference: Mechanisms contributing to central excitability changes during hearing loss. Pilati N, Ison MJ, Barker M, Mulheran M, Large CH, Forsythe ID, Matthias J, Hamann M.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 May 22;109(21):8292-7. Epub 2012 May 7

The research was funded by Wellcome Trust, Medisearch (running costs), GlaxoSmithkline (PhD studentship for Nadia Pilati), Royal Society (equipment grant).

Nadia Pilati (CPP Dept) performed all the electrophysiological experiments.

Matt Barker (CPP Dept) performed the electron microscopy experiments in collaboration with the electron microscopy suite here in Leicester.

Mike Mulheran (Medical Education Dept) helped us with the auditory brainstem response recordings (to assess hearing loss).

Matias Ison (Engineering Dept) performed the modelling using Matlab. His modelling guided us into exploring the possibility of the sheath being affected during hearing loss.

John Mathias (University of Plymouth) and Matias Ison generated the sound file that can be downloaded from the PNAS paper.

Earphones 'potentially as dangerous as noise from jet engines,' according to new study

University of Leicester research identifies for the first time how high volumes of sound damage nerve cell coating leading to temporary deafness

2012-08-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New research eclipses existing theories on moon formation

2012-08-29

Oxford, August 29, 2012 - The Moon is believed to have formed from a collision, 4.5 billion years ago, between Earth and an impactor the size of Mars, known as "Theia." Over the past decades scientists have simulated this process and reproduced many of the properties of the Earth-Moon system; however, these simulations have also given rise to a problem known as the Lunar Paradox: the Moon appears to be made up of material that would not be expected if the current collision theory is correct. A recent study published in Icarus proposes a new perspective on the theory in ...

Don't cut lifesaving ICDs during financial crisis, ESC warns

2012-08-29

Implantable devices for treating cardiac arrhythmias, which include ICDs, are already underused in parts of Eastern and Central Europe and there is a risk that the financial crisis could exacerbate the problem. The European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), a registered branch of the ESC, is tackling this issue through ICD for Life. The initiative aims to raise awareness about the importance of ICDs and sudden cardiac death in countries in Central and Eastern Europe.

ICD implantation rates in Europe vary widely, ranging from 1 ICD implantation per million inhabitants in ...

Gold standards of success defined for AF ablation

2012-08-29

The 2012 expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation was developed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), and the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society (ECAS) and published in their respective journals: Heart Rhythm, EP Europace (1) and the Journal of Interventional Cardiovascular Electrophysiology (JICE).

Since the previous consensus document was published in 2007 catheter and surgical ablation of AF have become standard treatments ...

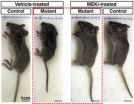

A CNIO team creates a unique mouse model for the study of aplastic anaemia

2012-08-29

Aplastic anaemia is characterised by a reduction in the number of the bone marrow cells that go on to form the different cell types present in blood (essentially red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets). In most cases, the causes of the disorder are hard to determine, but some patients have been found to have genetic alterations leading to a shortening of their telomeres (the end regions of chromosomes that protect and stabilise DNA).

A team at the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) led by María Blasco has successfully created a transgenic mouse model ...

Oversized fat droplets: Too much of a good thing

2012-08-29

KANSAS CITY, MO—As the national waistline expands, so do pools of intra-cellular fat known as lipid droplets. Although most of us wish our lipid droplets would vanish, they represent a cellular paradox: on the one hand droplets play beneficial roles by corralling fat into non-toxic organelles. On the other, oversized lipid droplets are associated with obesity and its associated health hazards.

Until recently researchers understood little about factors that regulate lipid droplet size. Now, a study from the Stowers Institute of Medical Research published in an upcoming ...

Climate change could increase levels of avian influenza in wild birds

2012-08-29

ANN ARBOR, Mich.—Rising sea levels, melting glaciers, more intense rainstorms and more frequent heat waves are among the planetary woes that may come to mind when climate change is mentioned. Now, two University of Michigan researchers say an increased risk of avian influenza transmission in wild birds can be added to the list.

Population ecologists Pejman Rohani and Victoria Brown used a mathematical model to explore the consequences of altered interactions between an important species of migratory shorebird and horseshoe crabs at Delaware Bay as a result of climate ...

ESC analysis reveals arrhythmia treatment gaps between Eastern and Western Europe

2012-08-29

The analysis was conducted using five editions of the EHRA White Book, which is produced by the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).

The EHRA White Book reports on the current status of arrhythmia treatments in the 54 ESC member countries and has been published every year since 2008. Data is primarily provided by the national cardiology societies and working groups of cardiac pacing and electrophysiology of each ESC country. Prospective data is collected on catheter ablation and on implantation of cardiovascular ...

TAVI restricted to very old or very sick patients

2012-08-29

The registry is part of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) EURObservational Research Programme (EORP) of surveys and registries.

Today's presentation reveals current usage of the most modern TAVI valves and catheters in Europe, and compares indications, techniques and outcomes between different countries. "TAVI is a new technology which has been introduced in Europe but many question marks remain on which patients are most suitable," said Professor Di Mario. "We set up this registry because it was important to have a clear picture of clinical practice in Europe. ...

Added benefit of fampridine is not proven

2012-08-29

Fampridine (trade name Fampyra®) has been approved in Germany since July 2011 for adult patients suffering from a higher grade walking disability (grades 4 to 7 on the EDSS disability status scale), as a result of multiple sclerosis (MS). The German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) has assessed the added benefit of the drug pursuant to the Act on the Reform of the Market for Medicinal Products (AMNOG). According to the findings, there is no proof of added benefit, as the manufacturer's dossier contains no evaluable study data for the comparison ...

Could a cancer drug potentially prevent learning disabilities in some kids?

2012-08-29

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — A drug originally developed to stop cancerous tumors may hold the potential to prevent abnormal brain cell growth and learning disabilities in some children, if they can be diagnosed early enough, a new animal study suggests.

The surprising finding sets the stage for more research on how anti-tumor medication might be used to protect the developing brains of young children with the genetic disease neurofibromatosis 1 -- and other diseases affecting the same cellular signaling pathway.

The findings, made in mice, are reported in the journal Cell ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

[Press-News.org] Earphones 'potentially as dangerous as noise from jet engines,' according to new studyUniversity of Leicester research identifies for the first time how high volumes of sound damage nerve cell coating leading to temporary deafness