(Press-News.org) This press release is available in German.

It had been thought that mothers delivering later in life have children that are less healthy as adults, because the body of the mother had already degenerated due to physiological effects like decreasing oocyte quality or a weakened placenta. In fact, what affects the health of the grown-up children is not the age of their mother but her education and the number of years she survives after giving birth and thus spends with her offspring. This is the conclusion of a new study by Mikko Myrskylä from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock, Germany carried out with data from 18,000 US children and their mothers.

According to Myrskylä's calculations, children born to mothers aged between 35 and 44 years are no less healthy later in life than those whose mothers delivered between ages 25 and 34. While it is still true that higher maternal age brings a greater risk of miscarriage and conditions like Trisomy 21, says demographer Myrskylä, "with respect to adult age early births appear to be more dangerous for children than late ones." Children born to mothers aged 24 and younger have a higher number of diagnosed conditions, die earlier, remain smaller in size and are more likely to be obese as adults.

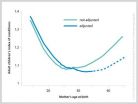

This is what Max Planck scientist Myrskylä discovered when he adjusted the US health data for the actual factors, the mother's education and date of death, which only simulates a negative effect of maternal age. When not correcting for these elements, adult offspring were in fact ill more often if they were born to older mothers. The adult children of women delivering between ages 35 and 44 appeared to have about ten percent higher incidence of health conditions than those born to mothers aged 25 to 34. However, in Myrskylä's corrected analysis the health effect shrank to under five percent and therefore lost its statistical significance. In other words, the negative effect of advanced maternal age up to 45 years vanishes into thin air. "The data suggests that what at first looks seems like a negative advanced maternal age effect is an illusion driven by the mother's education and the age at which the child loses the mother," says Mikko Myrskylä.

For younger mothers, the picture looks different: the earlier in life women give birth the more their children suffer from illnesses as adults. Children born to mothers between age 20 and 24 suffer from 5 percent more diseases than those born to mothers aged 25 to 34. The value is much higher, approximately 15 percent for those born to mothers aged 14 to 19 years. These results are statistically significant, and robust to correcting for the mother's education or other confounding factors.

The two crucial most crucial factors for offspring adult health turned out to be the mother's education and the number of years the mother and child were alive at the same time. The earlier a child lost her mother the worse her health was as an adult. This could be due to psychological effects accompanying the experience of losing a mother early, or because the time during which she could support her child economically and emotionally was shorter.

Most scientific studies analyzing how the age of the mother at birth influences the child's adult health (including Myrskylä's) survey children born in the early 20th century or even earlier. Data for children born more recently would not be suitable since their adult and old-age health could not yet be fully evaluated. In these earlier times, humans died much earlier and the risk of becoming an orphan at a young age was significantly higher. With increasing life expectancy, however, this has changed as generations can expect to spend many decades together, in particular in developed countries. Therefore the risk of losing a mother at a young age most probably is no longer critical for children born today.

Still relevant today is the educational background of the mother. Many studies prove that mothers with lower education level have adult offspring who have worse health. Notably, in the early 20th century when today's older people were born, parents with lower education continued to have children later in life, whereas better educated parents had less children at older ages. This led to the misinterpretation that high maternal age was harmful. In fact, it is the low parental education which is significant. This effect of advanced age no longer applies to children born today, as the relationship between maternal age and education is reversed. Today, the later in life a woman has a child the better their education. For modern health policy Mikko Myrskylä diffuses previous warnings: "At least with respect to children's adult health we don't need to worry about the currently increasing maternal age."

INFORMATION:

Original article:

Mikko Myrskylä

Maternal Age and Offspring Adult Health: Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study, Demography, OnlineFirst (DOI 10.1007/s13524-012-0132-x)

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0132-x

Advanced maternal age not harmful for adult children

Previously existing ideas on how advanced maternal age affects adult health of children have to be reconsidered

2012-09-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Multi-functional anti-inflammatory/anti-allergic developed by Hebrew University researcher

2012-09-06

Jerusalem, Sept. 6, 2012 – A synthetic, anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic family of drugs to combat a variety of illnesses while avoiding detrimental side effects has been developed by a Hebrew University of Jerusalem researcher.

The researcher is Saul Yedgar, who is the Walter and Greta Stiel Professor of Heart Studies at the Institute for Medical Research Israel-Canada at the Hebrew University Faculty of Medicine.

Inflammatory/allergic diseases affect billions of people worldwide, and treatments for these conditions are a major focus of the pharmaceutical industry. ...

Earlier treatment for young patients with chronic hepatitis B more effective in clearing virus

2012-09-06

Scientists from A*STAR's Singapore Institute for Clinical Sciences (SICS), together with clinical collaborators from London , discovered for the first time that children and young patients with chronic Hepatitis B Virus infection (HBV carriers) do have a protective immune response, contrary to current belief, and hence can be more suitable treatment candidates than previously considered.

This discovery by the team of scientists led by Professor Antonio Bertoletti, programme director and research director of the infection and immunity programme at SICS, could lead to ...

Mars's dramatic climate variations are driven by the Sun

2012-09-06

On Mars's poles there are ice caps of ice and dust with layers that reflect to past climate variations on Mars. Researchers from the Niels Bohr Institute have related the layers in the ice cap on Mars's north pole to variations in solar insolation on Mars, thus established the first dated climate history for Mars, where ice and dust accumulation has been driven by variations in insolation. The results are published in the scientific journal, Icarus.

The ice caps on Mars's poles are kilometres thick and composed of ice and dust. There are layers in the ice caps, which ...

A brain filter for clear information transmission

2012-09-06

This press release is available in German. Stefan Remy and colleagues at the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) and the University of Bonn have illuminated how this system works. "The system acts like a filter, only letting the most important impulses pass," explains Remy. "This produces the targeted neuronal patterns that are indispensible for long-term memory storage."

How does this refined control system work? How can inhibitory signals produce precise output signals? This was the question investigated by Remy and his colleagues. Scientists have known ...

Human genome far more active than thought

2012-09-06

The GENCODE Consortium expects the human genome has twice as many genes than previously thought, many of which might have a role in cellular control and could be important in human disease. This remarkable discovery comes from the GENCODE Consortium, which has done a painstaking and skilled review of available data on gene activity.

Among their discoveries, the team describe more than 10,000 novel genes, identify genes that have 'died' and others that are being resurrected. The GENCODE Consortium reference gene catalogue has been one of the underpinnings of the larger ...

Survival 'excellent' following living donor liver transplantation for acute liver failure

2012-09-06

Patients in Japan who underwent living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) for acute liver failure (ALF) were classified as having excellent outcomes, with ten-year survival at 73%. The findings, published in the September issue of Liver Transplantation, a journal of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), suggest that the type of liver disease or treatment plan does not affect long-term patient survival following LDLT. Donor and patient age, however, does impact long-term outcome post-transplant.

According to the AASLD, roughly 2,000 Americans ...

Destroyed coastal habitats produce significant greenhouse gas

2012-09-06

DURHAM, N.C. -- Destruction of coastal habitats may release as much as 1 billion tons of carbon emissions into the atmosphere each year, 10 times higher than previously reported, according to a new Duke led study.

Published online this week in PLOS ONE, the analysis provides the most comprehensive estimate of global carbon emissions from the loss of these coastal habitats to date: 0.15 to 1.2 billion tons. It suggests there is a high value associated with keeping these coastal-marine ecosystems intact as the release of their stored carbon costs roughly $6-$42 billion ...

Storm of 'awakened' transposons may cause brain-cell pathologies in ALS, other illnesses

2012-09-06

Cold Spring Harbor, NY – A team of neuroscientists and informatics experts at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) reports important progress in an effort to understand the relationship between transposons – sequences of DNA that can jump around within the genome, potentially causing great damage – and mechanisms involved in serious neurodegenerative disorders including ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig's disease), FTLD (frontotemporal lobar degeneration) and Alzheimer's disease.

A close analysis of previously unanalyzed genome data has led ...

Childhood sexual abuse linked to later heart attacks in men

2012-09-06

TORONTO, ON – Men who experienced childhood sexual abuse are three times more likely to have a heart attack than men who were not sexually abused as children, according to a new study from researchers at the University of Toronto. The researchers found no association between childhood sexual abuse and heart attacks among women.

In a paper published online this week in the journal Child Abuse & Neglect, investigators examined gender-specific differences in a representative sample of 5095 men and 7768 women aged 18 and over, drawn from the Center for Disease Control's 2010 ...

Promising new drug target for inflammatory lung diseases

2012-09-06

New Rochelle, NY, September 6, 2012—The naturally occurring cytokine interleukin-18, or IL-18, plays a key role in inflammation and has been implicated in serious inflammatory diseases for which the prognosis is poor and there are currently limited treatment options. Therapies targeting IL-18 could prove effective against inflammatory diseases of the lung including bronchial asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), as described in a review article published in Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research (http://www.liebertpub.com/jir), a peer-reviewed publication ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Reconstructing the world’s ant diversity in 3D

UMD entomologist helps bring the world’s ant diversity to life in 3D imagery

ESA’s Mars orbiters watch solar superstorm hit the Red Planet

The secret lives of catalysts: How microscopic networks power reactions

Molecular ‘catapult’ fires electrons at the limits of physics

Researcher finds evidence supporting sucrose can help manage painful procedures in infants

New study identifies key factors supporting indigenous well-being

Bureaucracy Index 2026: Business sector hit hardest

ECMWF’s portable global forecasting model OpenIFS now available for all

Yale study challenges notion that aging means decline, finds many older adults improve over time

Korean researchers enable early detection of brain disorders with a single drop of saliva!

Swipe right, but safer

Duke-NUS scientists identify more effective way to detect poultry viruses in live markets

Low-intensity treadmill exercise preconditioning mitigates post-stroke injury in mouse models

How moss helped solve a grave-robbing mystery

How much sleep do teens get? Six-seven hours.

Patients regain weight rapidly after stopping weight loss drugs – but still keep off a quarter of weight lost

GLP-1 diabetes drugs linked to reduced risk of addiction and substance-related death

Councils face industry legal threats for campaigns warning against wood burning stoves

GLP-1 medications get at the heart of addiction: study

Global trauma study highlights shared learning as interest in whole blood resurges

Almost a third of Gen Z men agree a wife should obey her husband

Trapping light on thermal photodetectors shatters speed records

New review highlights the future of tubular solid oxide fuel cells for clean energy systems

Pig farm ammonia pollution may indirectly accelerate climate warming, new study finds

Modified biochar helps compost retain nitrogen and build richer soil organic matter

First gene regulation clinical trials for epilepsy show promising results

Life-changing drug identified for children with rare epilepsy

Husker researchers collaborate to explore fear of spiders

Mayo Clinic researchers discover hidden brain map that may improve epilepsy care

[Press-News.org] Advanced maternal age not harmful for adult childrenPreviously existing ideas on how advanced maternal age affects adult health of children have to be reconsidered