(Press-News.org) A mysterious form of cell death, coded in proteins and enzymes, led to a discovery by UNC researchers uncovering a prime suspect for new cancer drug development.

CIB1 is a protein discovered in the lab of Leslie Parise, PhD , professor and chair of the department of biochemistry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The small calcium binding protein is found in all kinds of cells.

Cassandra Moran, DO, was a pediatric oncology fellow at UNC prior to accepting a faculty position at Duke University. She is interested in neuroblastoma, a deadly form of childhood brain cancer. While working in the Parise lab at UNC as a resident, she found that decreasing CIB1 in neuroblastoma cells caused cell death.

Cancer is a disease of uncontrolled cell growth, so the ability to cause cancer cell death in the lab is exciting to researchers – but the UNC team couldn't figure out how it was happening.

Tina Leisner, PhD, a UNC research associate in biochemistry, picked up where Dr. Moran left off when she returned to her clinical training.

"It was a mystery how loss of CIB1 was causing cell death. We knew that it wasn't the most common mechanism for programmed cell death, called apoptosis, which occurs when enzymes called caspases become activated, leading to the destruction of cellular DNA. These cells were not activating caspases, yet they were dying. It was fascinating, but frustrating at the same time," said Leisner.

What Dr. Leisner and her colleagues found, in the end, is that CIB1 is a master regulator of two pathways that cancer cells use to avoid normal mechanisms for programmed cell death. These two pathways, researchers believe, create "alternate routes" for cell survival and proliferation that may help cancer cells outsmart drug therapy. When one pathway is blocked, the other still sends signals downstream to cause cancer cell survival.

"What we eventually discovered is that CIB1 sits on top of two cell survival pathways, called PI3K/AKT and MEK/ERK. When we knock out CIB1, both pathways grind to a halt. Cells lose AKT signaling, causing another enzyme called GAPDH to accumulate in the cell's nucleus.Cells also lose ERK signaling, which together with GAPDH accumulation in the nucleus cause neuroblastoma cell death. In the language of people who aren't biochemists, knocking out CIB1 cuts off the escape routes for the cell signals that cause uncontrolled growth, making CIB1 a very promising drug target," said Dr. Parise.

This multi-pathway action is key to developing more effective drugs. Despite the approval of several targeted therapies in recent years, many cancers eventually become resistant to therapy.

"What is even more exciting," Leisner adds, "is that it works in completely different types of cancer cells. We successfully replicated the neuroblastoma findings in triple-negative breast cancer cells, meaning that new drugs targeted to CIB1 might work very broadly."

###The team's findings were published in the journal Oncogene. In addition to Drs. Leisner, Moran and Parise, Stephen P. Holly, PhD, contributed to the research.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under awards number HL07149T32 and 5R01HL092544.

Cell death mystery yields new suspect for cancer drug development

2012-09-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Computer program can identify rough sketches

2012-09-13

VIDEO:

To develop a program that allows computers to recognize rough sketches, we need to understand how humans actually sketch objects. Researchers from Brown University and the Technical University of Berlin...

Click here for more information.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — First they took over chess. Then Jeopardy. Soon, computers could make the ideal partner in a game of Draw Something (or its forebear, Pictionary).

Researchers from Brown University and the ...

Effects of stopping alcohol consumption on subsequent risk of esophageal cancer

2012-09-13

Cancer of the oesophagus is becoming more common in Europe and North America. Around 7,800 people in the UK are diagnosed each year. The exact causes of this cancer aren't fully understood. It appears to be more common in people who have long-term acid reflux (backflow of stomach acid into the oesophagus). Other factors that can affect the risk of developing cancer of the oesophagus include:

Gender – It is more common in men than in women.

Age – The risk of developing oesophageal cancer increases as we get older. It occurs most commonly in people over 45.

Smoking ...

U-M guidelines help family physicians evaluate, manage urinary incontinence for women

2012-09-13

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — Millions of women experience a loss of bladder control, or urinary incontinence, in their lifetime.

It's a common and often embarrassing problem that many patients don't bring up with their doctors – and when they do, it may be mentioned as a casual side note during a visit for more pressing medical issues.

Now, new guidelines from doctors at the University of Michigan Health System offer family physicians a step-by-step guide for the evaluation of urinary leakage, to prevent this quality-of-life issue from being ignored.

"I think a lot of physicians ...

Parental divorce linked to stroke in males

2012-09-13

TORONTO, ON – Men with divorced parents are significantly more likely to suffer a stroke than men from intact families, shows a new study from the University of Toronto.

The study, to be published this month in the International Journal of Stroke, shows that adult men who had experienced parental divorce before they turned 18 are three times more likely to suffer a stroke than men whose parents did not divorce. Women from divorced families did not have a higher risk of stroke than women from intact families.

"The strong association we found for males between parental ...

Lack of oxygen in cancer cells leads to growth and metastasis

2012-09-13

It seems as if a tumor deprived of oxygen would shrink. However, numerous studies have shown that tumor hypoxia, in which portions of the tumor have significantly low oxygen concentrations, is in fact linked with more aggressive tumor behavior and poorer prognosis. It's as if rather than succumbing to gently hypoxic conditions, the lack of oxygen commonly created as a tumor outgrows its blood supply signals a tumor to grow and metastasize in search of new oxygen sources – for example, hypoxic bladder cancers are likely to metastasize to the lungs, which is frequently deadly. ...

Laser-powered 'needle' promises pain-free injections

2012-09-13

VIDEO:

The movie shows the injector firing into open air without a skin or gel target. The jet, which is approximately the diameter of a human hair, seems dispersed but a...

Click here for more information.

WASHINGTON, Sept. 13—From annual flu shots to childhood immunizations, needle injections are among the least popular staples of medical care. Though various techniques have been developed in hopes of taking the "ouch" out of injections, hypodermic needles are still the ...

IU chemist develops new synthesis of most useful, yet expensive, antimalarial drug

2012-09-13

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- In 2010 malaria caused an estimated 665,000 deaths, mostly among African children. Now, chemists at Indiana University have developed a new synthesis for the world's most useful antimalarial drug, artemisinin, giving hope that fully synthetic artemisinin might help reduce the cost of the live-saving drug in the future.

Effective deployment of ACT, or artemisinin-based combination therapy, has been slow due to high production costs of artemisinin. The World Health Organization has set a target "per gram" cost for artemisinin of 25 cents or less, but ...

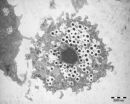

Study of giant viruses shakes up tree of life

2012-09-13

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A new study of giant viruses supports the idea that viruses are ancient living organisms and not inanimate molecular remnants run amok, as some scientists have argued. The study reshapes the universal family tree, adding a fourth major branch to the three that most scientists agree represent the fundamental domains of life.

The new findings appear in the journal BMC Evolutionary Biology.

The researchers used a relatively new method to peer into the distant past. Rather than comparing genetic sequences, which are unstable and change rapidly over time, ...

Scientists use sound waves to levitate liquids, improve pharmaceuticals

2012-09-13

It's not a magic trick and it's not sleight of hand – scientists really are using levitation to improve the drug development process, eventually yielding more effective pharmaceuticals with fewer side effects.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory have discovered a way to use sound waves to levitate individual droplets of solutions containing different pharmaceuticals. While the connection between levitation and drug development may not be immediately apparent, a special relationship emerges at the molecular level.

At the molecular ...

Increased dietary fructose linked to elevated uric acid levels and lower liver energy stores

2012-09-13

Obese patients with type 2 diabetes who consume higher amounts of fructose display reduced levels of liver adenosine triphosphate (ATP)—a compound involved in the energy transfer between cells. The findings, published in the September issue of Hepatology, a journal of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, indicate that elevated uric acid levels (hyperuricemia) are associated with more severe hepatic ATP depletion in response to fructose intake.

This exploratory study, funded in part by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and ...