(Press-News.org) HOUSTON – (Sept. 25, 2012) – The human body is proficient at making collagen. And human laboratories are getting better at it all the time.

In a development that could lead to better drug design and new treatments for disease, Rice University researchers have made a major step toward synthesizing custom collagen. Rice scientists who have learned how to make collagen – the fibrous protein that binds cells together into organs and tissues – are now digging into its molecular structure to see how it forms and interacts with biological systems.

Jeffrey Hartgerink, an associate professor of chemistry and of bioengineering, and his former graduate student Jorge Fallas, now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington, wrote a new computer program that predicts the most stable structures of nanometer-sized collagen. In nature, these small structures link into chains that serve as connective tissue in the body. Hartgerink and Fallas followed up the computer research by making and testing the collagen detailed in their calculations.

Their success, reported today in the online journal Nature Communications, will be of interest to physicians and scientists who work in reconstructive surgery, cosmetics and tissue engineering as well as to researchers investigating collagen protein interactions that could lead to new treatments for cancer and other diseases.

"Collagen is an odd protein. On one hand, it's the most abundant protein in the human body," said Hartgerink, who in a previous work unveiled a new way to synthesize self-assembling collagen. "It basically is the connective fiber that holds cells together; without it you'd turn into a big puddle.

"By mass, collagen is the most common protein there is. But it's different from almost any other you might look at," he said.

Hartgerink likened collagen to DNA with a structural twist, as it has not two but three intertwining peptide strands. "Watson and Crick, when they were first trying to understand DNA, figured out the underlying code for how all the base pairs fit together," he said. "Collagen is similar, except there are three strands. In this paper, we've started to crack the code of which amino acids go with what others to stabilize the structure."

While scientists have made a great deal of progress defining the structures of other proteins, "only a small group of us have been interested in collagen. And because of that, our understanding of it has lagged behind," he said.

In their new work, Hartgerink and Fallas analyzed charged interactions between amino acids that attract one strand to another (and in this case, yet another) to form the triple helix. "We look at positively charged and negatively charged amino acids and where they need to be aligned to result in stabilization," Hartgerink said.

In the same way three-color images must be properly aligned for a viewer to see a complete picture, the three strands of a collagen protein must be in register for the protein to carry out its function.

"Collagen does more than hold cells together," he said. "It also binds other proteins that have interesting functions. Those proteins will attach to collagen, and then cells come along and bind to those proteins. Based on that interaction, a cell will then 'decide' how to behave or differentiate into a different type of cell."

Hartgerink said that property makes collagen especially valuable for biological scaffolds, materials that are under intense study as a way to grow new body parts – even entire organs – to replace damaged ones.

Hartgerink said strand alignment also determines a collagen helix's stability. The computer program designed by Fallas and Hartgerink calculates the stability of each possible alignment of a given set of peptide strands – 27 in all – to find the best matches of positively and negatively charged amino acids. It then assigns each set a score, based on the net positive or negative charge of the entire helix.

"If we have a positive charge in a peptide sequence, it will destabilize the triple helix, and we score that as a minus 1," he said. "If we have a negative charge, that also destabilizes the helix and we also score that as a minus 1. But if those charges line up in what we call the axial geometry, it negates the destabilization. This triple helix would have a score of 0, which is good.

"We create huge, theoretical populations of collagen sequences and score all of them," he said. "We find out which are closest to this magical score of 0 and throw out all the other ones." That tells the researchers which sequences are likely to self-assemble into the most stable helixes. "The math looks complicated, but a personal computer can generate one of these sequences in one or two minutes of processing time. It's not super sophisticated." He said the code will be available on his group's home page for other researchers to try.

Hartgerink's lab, based at Rice's BioScience Research Collaborative, has the unusual capacity to carry out both theoretical and experimental sides of the work. While the program generates test sequences in minutes on a desktop computer, synthesis and analysis of actual collagen takes much more effort.

"Once you have a sequence, you want to test it to see if it actually works," he said. "The math is useless if it's not predicting reality. Our proof-of-principle showed the computer code can be used to design a triple helix that folds properly. Now that we know how to do this, we can think about making collagen biomaterials for things like scaffolding, or to test protein/collagen receptor interactions, which people have been trying to demonstrate for a long time."

He said the new work could help researchers decipher collagen's role in the metastasis of cancer. "Cancer cells need to be able to degrade collagen in order to move from organ to organ. We need to understand the structure of collagen to learn how they do that," Hargerink said. "Blood clots happen because specific proteins recognize a collagen sequence. If we don't understand the structure, we can't assist clotting to heal a wound or help people who have overclotting problems.

"All these targets are critical but they're very difficult to approach when we don't fundamentally understand collagen structure," he said. "We're not solving all those problems here, but this is a good first step."

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation, the Robert A. Welch Foundation and the Norman Hackerman Advanced Research Program of Texas.

This news release can be found online at news.rice.edu.

Read the abstract at http://www.nature.com/ncomms/journal/v3/n9/full/ncomms2084.html

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews

Related Materials:

Hartgerink lab: http://www.ruf.rice.edu/~jdh/group.html

BioScience Research Collaborative: http://brc.rice.edu/home/

Images for download:

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/axial_black.jpg

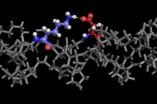

A program developed at Rice University details stable forms of collagen proteins for synthesis in the lab. The ability to synthesize custom collagen could lead to better drug design and treatment of disease. The colored portion of the molecule in this illustration shows positively charged lysine and negatively charged aspartate interacting in the required axial geometry that stabilizes the triple helix. (Credit: Hartgerink Lab/Rice University)

Rice University lab encodes collagen

Program defines stable sequences for synthesis, could help fight disease, design drugs

2012-09-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Hubble goes to the 'eXtreme' to assemble the deepest ever view of the universe

2012-09-26

The Hubble Ultra Deep Field is an image of a small area of space in the constellation of Fornax (The Furnace), created using Hubble Space Telescope data from 2003 and 2004. By collecting faint light over one million seconds of observation, the resulting image revealed thousands of galaxies, both nearby and very distant, making it the deepest image of the Universe ever taken at that time.

The new full-colour XDF image is even more sensitive than the original Hubble Ultra Deep Field image, thanks to the additional observations, and contains about 5500 galaxies, even within ...

Oropharyngeal cancer patients with HPV have a more robust response to radiation therapy

2012-09-26

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) — UC Davis cancer researchers have discovered significant differences in radiation-therapy response among patients with oropharyngeal cancer depending on whether they carry the human papillomavirus (HPV), a common sexually transmitted virus. The findings, published online today in The Laryngoscope Journal, could lead to more individualized radiation treatment regimens, which for many patients with HPV could be shorter and potentially less toxic.

HPV-related cancers of the oropharynx (the region of the throat between the soft palate and the epiglottis, ...

Images reveal potential for NIR imaging to detect success of breast reconstruction

2012-09-26

In 2010 breast reconstruction entered the Top Five list of reconstructive procedures in the US, with 93,000 procedures performed, up 8% from 2009, and 18% from 2000. This is among the most common skin flap procedure performed.

Skin flaps are typically used to cover areas of tissue loss or defects that arise as a result of traumatic injury, reconstruction after cancer excision and repair of congenital defects. In the case of a mastectomy—the surgical removal of the breast—skin flaps are commonly used to create a new breast. Most commonly these flaps are derived from the ...

Hotter might be better at energy-intensive data centers

2012-09-26

As data centres continue to come under scrutiny for the amount of energy they use, researchers at University of Toronto Scarborough (UTSC) have a suggestion: turn the air conditioning down.

"We see our results as strong evidence that most organizations could run their data centers hotter than they currently are without making significant sacrifices in system reliability," says Bianca Schroeder, a UTSC assistant professor of computer science.

As data centres have proliferated they have required more energy, accounting now for about 1 percent of global electricity usage. ...

Starting to snore during pregnancy could indicate risk for high blood pressure, U-M study says

2012-09-26

Ann Arbor, Mich. – Women who begin snoring during pregnancy are at strong risk for high blood pressure and preeclampsia, according to research from the University of Michigan.

The research, published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, showed pregnancy-onset snoring was strongly linked to gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, says lead author Louise O'Brien, Ph.D., associate professor in U-M's Sleep Disorders Center.

"We found that frequent snoring was playing a role in high blood pressure problems, even after we had accounted for other known ...

Urban coyotes never stray: New study finds 100 percent monogamy

2012-09-26

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Coyotes living in cities don't ever stray from their mates, and stay with each other till death do them part, according to a new study.

The finding sheds light on why the North American cousin of the dog and wolf, which is originally native to deserts and plains, is thriving today in urban areas.

Scientists with Ohio State University who genetically sampled 236 coyotes in the Chicago area over a six-year period found no evidence of polygamy - of the animals having more than one mate - nor of one mate ever leaving another while the other was still alive.

This ...

Prison rehab tied to parole decisions

2012-09-26

According to a new study co-authored by Simon Fraser University economics professor Steeve Mongrain, parole board decisions can have a huge impact on whether or not prisoners are motivated to rehabilitate.

The Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, has just published their study Rehabilitated or Not: An Informational Theory of Parole Decisions online.

Mongrain and his colleagues argue that parole boards need to consider the length of prisoners' original sentences, as well as their behaviour in prison, in granting early parole and determining eligibility for parole ...

New tool for CSI? Geographic software maps distinctive features inside bones

2012-09-26

COLUMBUS, Ohio – A common type of geographic mapping software offers a new way to study human remains.

In a recent issue of the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, researchers describe how they used commercially available mapping software to identify features inside a human foot bone – a new way to study human skeletal variation.

David Rose, a Captain in the Ohio State University Police Division and doctoral student in anthropology, began the project to determine whether the patterns of change inside the bones of human remains could reveal how the bones were ...

Improved communication could reduce STD epidemic among black teenagers

2012-09-26

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Black urban teenagers from low-income families face a rate of sexually transmitted disease up to 10 times higher than their white counterparts, but recent studies at Oregon State University have identified approaches to prevention programs that might reduce this problem.

The research, based on interviews of black adolescents ages 15-17 in San Francisco and Chicago, found that information from parents, teachers and other caring adults is actually listened to, more than the adults might think. And the problem of youth getting "mixed messages" from different ...

Population aging will have long-term implications for economy

2012-09-26

WASHINGTON — The aging of the U.S. population will have broad economic consequences for the country, particularly for federal programs that support the elderly, and its long-term effects on all generations will be mediated by how -- and how quickly -- the nation responds, says a new congressionally mandated report from the National Research Council. The unprecedented demographic shift in which people over age 65 make up an increasingly large percentage of the population is not a temporary phenomenon associated with the aging of the baby boom generation, but a pervasive ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Rice University lab encodes collagenProgram defines stable sequences for synthesis, could help fight disease, design drugs