(Press-News.org) Atherosclerosis – the hardening of arteries that is a primary cause of cardiovascular disease and death – has long been presumed to be the fateful consequence of complicated interactions between overabundant cholesterol and resulting inflammation in the heart and blood vessels.

However, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, with colleagues at institutions across the country, say the relationship is not exactly what it appears, and that a precursor to cholesterol actually suppresses inflammatory response genes. This precursor molecule could provide a new target for drugs designed to treat atherosclerosis, which kills tens of thousands of Americans annually.

The findings are published in the September 28, 2012 issue of Cell.

Lurking within our arterial walls are immune system cells called macrophages (Greek for "big eater") whose essential function is to consume other cells or matter identified as foreign or dangerous. "When they do that, it means they consume the other cell's store of cholesterol," said Christopher Glass, MD, PhD, a professor in the Departments of Medicine and Cellular and Molecular Medicine and senior author of the Cell study. "As a result, they've developed very effective ways to metabolize the excess cholesterol and get rid of it."

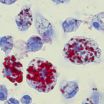

But some macrophages fail to properly dispose of the excess cholesterol, allowing it to instead accumulate inside them as foamy lipid (fat) droplets, which gives the cells their particular name: macrophage foam cells.

These foam macrophages produce molecules that summon other immune cells and release molecules, signaling certain genes to launch an inflammatory response. Glass said conventional wisdom has long assumed atherosclerotic lesions – clumps of fat-laden foam cells massed within arterial walls – were the unhealthy consequence of an escalating association between unregulated cholesterol accumulation and inflammation.

Glass and colleagues wanted to know exactly how cholesterol accumulation led to inflammation, and why the macrophages failed to do their job. Using specialized mouse models that produced abundant macrophage foam cells, they made two unexpected discoveries that upend previous assumptions about how lesions form and how atherosclerosis might be more effectively treated.

"The first is that foam cell formation suppressed activation of genes that promote inflammation. That's exactly the opposite of what we thought happened," said Glass. "Second, we identified a molecule that helps normal macrophages manage cholesterol balance. When it's in abundance, it turns on cellular pathways to get rid of cholesterol and turns off pathways for producing more cholesterol."

That molecule is desmosterol – the final precursor in the production of cholesterol, which cells make and use as a structural component of their membranes. In atherosclerotic lesions, Glass said the normal function of desmosterol appears to be "crippled."

"That's the next thing to study; why that happens," Glass said, hypothesizing that the cause may be linked to overwhelming, pro-inflammatory signals coming from proteins called Toll-like receptors on macrophages and other cells that, like macrophages, are critical elements of the immune system.

The identification of desmosterol's ability to reduce macrophage cholesterol presents researchers and drug developers with a potential new target for reducing the risk of atherosclerosis.

Glass noted that a synthetic molecule similar to desmosterol already exists, offering an immediate test-case for new studies. In addition, scientists in the 1950s developed a drug called triparanol that inhibited cholesterol production, effectively boosting desmosterol levels. The drug was sold as a heart disease medication, but later discovered to cause severe side effects, including blindness from an unusual form of cataracts. It was pulled from the market and abandoned.

"We've learned a lot in 50 years," said Glass. "Maybe there's a way now to create a new drug that mimics the cholesterol inhibition without the side effects."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors are first author Nathanael J. Spann, Norihito Shibata, Donna Reichart, Jesse N. Fox and Daniel Heudobler, UCSD Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine; Lana X. Garmire, UCSD Department of Bioengineering; Jeffrey G. McDonald and David W. Russell, Department of Molecular Genetics, UT Southwestern Medical Center; David S. Myers, Stephen B. Milne and Alex Brown, Department of Pharmacology, Vanderbilt Institute of Chemical Biology; Iftach Shaked and Klaus Ley, La Jolla Institute of Allergy and Immunology; Christian R.H. Raetz, Department of Biochemistry, Duke University School of Medicine; Elaine W. Wang, Samuel L. Kelly, M. Cameron Sullards and Alfred H. Merrill, Jr., Schools of Biology, Chemistry and Biochemistry and the Parker H. Petit Institute of Bioengineering and Bioscience, George Institute of Technology; Edward A. Dennis, UCSD Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry; Andrew C. Li, Sotirios Tsimikas and Oswald Quehenberger, UCSD Department of Medicine; Eoin Fahy, UCSD Department of Bioengineering; and Shankar Subramaniam, UCSD Departments of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Bioengineering and Chemistry and Biochemistry.

Funding for this research came, in part, from National Institutes of Health grants GM U54069338 (to the LIPID MAPS Consortium), P01 HC088093 and P01 DK074868.

New way of fighting high cholesterol upends assumptions

2012-09-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Mayo Clinic finds way to weed out problem stem cells, making therapy safer

2012-09-27

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- Mayo Clinic researchers have found a way to detect and eliminate potentially troublemaking stem cells to make stem cell therapy safer. Induced Pluripotent Stem cells, also known as iPS cells, are bioengineered from adult tissues to have properties of embryonic stem cells, which have the unlimited capacity to differentiate and grow into any desired types of cells, such as skin, brain, lung and heart cells. However, during the differentiation process, some residual pluripotent or embryonic-like cells may remain and cause them to grow into tumors.

"Pluripotent ...

Scientists find molecular link to obesity and insulin resistance in mice

2012-09-27

BOSTON--Flipping a newly discovered molecular switch in white fat cells enabled mice to eat a high-calorie diet without becoming obese or developing the inflammation that causes insulin resistance, report scientists from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

The researchers say the results, to be published in the Sept. 28 issue of the journal Cell, provide the first known molecular link between thermogenesis (burning calories to produce heat) and the development of inflammation in fat cells.

These two processes had been previously thought to be controlled separately. Thermogenesis ...

Canadian science and technology is healthy and growing, says expert panel

2012-09-27

AUDIO:

An authoritative, evidence-based assessment of the state of science and technology in Canada has found that Canadian science and technology is healthy, growing and internationally respected. Over the past five...

Click here for more information.

Ottawa (September 27th, 2012) - An authoritative, evidence-based assessment of the state of science and technology in Canada has found that Canadian science and technology is healthy, growing and internationally respected. Over ...

Shared pathway links Lou Gehrig's disease with spinal muscular atrophy

2012-09-27

Researchers of motor neuron diseases have long had a hunch that two fatal diseases, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), might somehow be linked. A new study confirms that this link exists.

"Our study is the first to link the two diseases on a molecular level in human cells," said Robin Reed, Harvard Medical School professor of cell biology and lead investigator of the study.

The results will be published online in the September 27 issue of Cell Reports.

ALS, or Lou Gehrig's disease, which has an adult onset, affects neurons that ...

Major cancer protein amplifies global gene expression, NIH study finds

2012-09-27

Scientists may have discovered why a protein called MYC can provoke a variety of cancers. Like many proteins associated with cancer, MYC helps regulate cell growth. A study carried out by researchers at the National Institutes of Health and colleagues found that, unlike many other cell growth regulators, MYC does not turn genes on or off, but instead boosts the expression of genes that are already turned on.

These findings, which will be published in Cell on Sept. 28, could lead to new therapeutic strategies for some cancers.

"We carried out a highly sophisticated ...

Obesity-related hormone discovered in fruit flies

2012-09-27

Researchers have discovered in fruit flies a key metabolic hormone thought to be the exclusive property of vertebrates. The hormone, leptin, is a nutrient sensor, regulating energy intake and output and ultimately controlling appetite. As such, it is of keen interest to researchers investigating obesity and diabetes on the molecular level. But until now, complex mammals such as mice have been the only models for investigating the mechanisms of this critical hormone. These new findings suggest that fruit flies can provide significant insights into the molecular underpinnings ...

Aggressive cancer exploits MYC oncogene to amplify global gene activity

2012-09-27

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (September 27, 2012) – For a cancer patient, over-expression of the MYC oncogene is a bad omen.

Scientists have long known that in tumor cells, elevated levels of MYC's protein product, c-Myc, are associated with poor clinical outcomes, including increased rates of metastasis, recurrence, and mortality. Yet decades of research producing thousands of scientific papers on the subject have failed to consistently explain precisely how c-Myc exerts its effects across a broad range of cancer types. Until now, that is.

The prevailing theory emerging from ...

Landmark guidelines for optimal quality care of geriatric surgical patients just released

2012-09-27

Chicago (September 27, 2012)—New comprehensive guidelines for the pre- operative care of the nation's elderly patients have been issued by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) and the American Geriatrics Society (AGS). The joint guidelines—published in the October issue of the Journal of the American College of Surgeons—apply to every patient who is 65 years and older as defined by Medicare regulations. The guidelines are the culmination of two years of research and analysis by a multidisciplinary expert panel representing the ACS and AGS, as well as by expert representatives ...

Uptick in cinematic smoking

2012-09-27

Top box office films last year showed more onscreen smoking than the prior year, reversing five years of steady progress in reducing tobacco imagery in movies, according to a new UCSF study.

Moreover, many of the top-grossing films of 2011 with significant amounts of smoking targeted a young audience, among them the PG-rated cartoon Rango and X-Men: First Class." The more smoking young people see in movies, the more likely they are to start smoking, the U.S. Surgeon General has reported.

The study will be available September 27, 2012 in Preventing Chronic Disease Journal, ...

Breakthrough in kitchen furniture production: Biocomposites challenge chipboard

2012-09-27

Biocomposites challenge chipboard as furniture material. Researchers at VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland have developed a kitchen furniture framework material from plastic polymers reinforced with natural fibre. The new material reduces raw materials consumption by 25 per cent and the carbon footprint of production by 35 per cent.

"The frames are lighter by nearly a third because they contain more air," says VTT's Research Professor Ali Harlin. "Wastage during production is also reduced. This is a generational shift that revolutionizes both manufacturing techniques ...