(Press-News.org) Researchers at Queen Mary, University of London have discovered how a key molecule controls the body's inflammatory responses. The molecule, known as p110delta, fine-tunes inflammation to avoid excessive reactions that can damage the organism. The findings, published in Nature Immunology today (30 September), could be exploited in vaccine development and new cancer therapies.

A healthy immune system reacts to danger signals – from microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses, or from the body's own rogue cells, such as cancer cells. This tightly controlled reaction starts with an inflammatory phase that alerts and activates the body to react against the danger signals. Once the danger has been cleared, it is critical that the body's inflammatory phase is shut down to avoid overreaction.

Control over the timing of inflammation is essential and is disrupted in a range of diseases: inflammation that is triggered too quickly or not controlled appropriately can lead to a potentially lethal endotoxic (septic) shock or, in a more chronic state, contribute to the development of diseases such as cancer, arthritis, asthma and multiple sclerosis.

A better understanding of the control mechanisms involved in orchestrating the body's inflammatory response will help in the development of better and more targeted treatments for a variety of diseases.

Professor Bart Vanhaesebroeck, from the Barts Cancer Institute at Queen Mary, University of London, who supervised the research, said: "For years scientists have been puzzled by the way in which p110delta can both fuel and restrain inflammatory reactions in the body. Thanks to the improved understanding that we have achieved through use of genetics and pharmacology, we have now identified one of the specific pathways that p110delta controls."

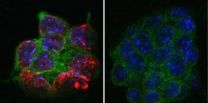

The researchers found that p110delta balances the immune response by regulating a particular type of immune cell, the dendritic cell. These cells sense and initiate an immune response, primarily provoking inflammation when they encounter "foreign bodies", including bacteria. By using dendritic cells from mice that lacked active p110delta, the study found that p110delta controls the transition of a bacteria-sensing receptor (TLR4) from the surface of the dendritic cell into its interior, a key step which allows the dendritic cell to initiate the shut-down phase of the inflammation.

Dr Ezra Aksoy, from the Barts Cancer Institute, the first author of the paper, said: "Temporarily interfering with p110delta activity could allow us to modulate the balance between the inflammatory and anti-inflammatory pathways, opening up new therapeutic avenues to be exploited in the fields of vaccination, cancer immunotherapy and chronic inflammatory diseases."

### END

Researchers discover key mechanism for controlling the body's inflammatory response

2012-10-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers discover gene that causes deafness

2012-10-01

CINCINNATI—Researchers at the University of Cincinnati (UC) and Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center have found a new genetic mutation responsible for deafness and hearing loss associated with Usher syndrome type 1.

These findings, published in the Sept. 30 advance online edition of the journal Nature Genetics, could help researchers develop new therapeutic targets for those at risk for this syndrome.

Partners in the study included the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), Baylor College of Medicine and the University of ...

New pathogen epidemic identified in sub-Saharan Africa

2012-10-01

A new study out today (Sunday 30 September) reveals that the emergence and spread of a rapidly evolving invasive intestinal disease, that has a significant mortality rate (up to 45%) in infected people in sub-Saharan Africa, seems to have been potentiated by the HIV epidemic in Africa.

The team found that invasive non-Typhoidal Salmonella (iNTS) disease is caused by a new form of the bacteria Salmonella Typhimurium that has spread from two different focal hubs in Southern and Central Africa beginning 52 and 35 years ago, respectively. They also found that one of the ...

Climate change could cripple southwestern forests

2012-10-01

Combine the tree-ring growth record with historical information, climate records, and computer-model projections of future climate trends, and you get a grim picture for the future of trees in the southwestern United States. That's the word from a team of scientists from Los Alamos National Laboratory, the U.S. Geological Survey, the University of Arizona, and other partner organizations.

If the Southwest is warmer and drier in the near future, widespread tree death is likely and would cause substantial changes in the distribution of forests and of species, the researchers ...

Common RNA pathway found in ALS and dementia

2012-10-01

Two proteins previously found to contribute to ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, have divergent roles. But a new study, led by researchers at the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, shows that a common pathway links them.

The discovery reveals a small set of target genes that could be used to measure the health of motor neurons, and provides a useful tool for development of new pharmaceuticals to treat the devastating disorder, which currently has no treatment or cure.

Funded in part by ...

The genetics of white finger disease

2012-10-01

Vibration-induced white finger disease (VWF) is caused by continued use of vibrating hand held machinery (high frequency vibration >50 Hz), and affects tens of thousands of people. New research published in BioMed Central's open access journal Clinical Epigenetics finds that people with a genetic polymorphism (A2191G) in sirtuin1 (SIRT1), a protein involved in the regulation of endothelial NOS (eNOS), are more likely to suffer from vibration-induced white finger disease.

VWF (also known as hand arm vibration syndrome (HAVS)) is a secondary form of Raynaud's disease involving ...

Breast cancer recurrence defined by hormone receptor status

2012-10-01

Human epidermal growth factor (HER2) positive breast cancers are often treated with the same therapy regardless of hormone receptor status. New research published in BioMed Central's open access journal Breast Cancer Research shows that women whose HER2 positive cancer was also hormone (estrogen and progesterone) receptor (HR) negative had an increased risk of early death, and that their cancer was less likely to recur in bone than those whose cancer retained hormone sensitivity.

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease with many different subtypes. HR positive cancer ...

Scientists find missing link between players in the epigenetic code

2012-10-01

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Over the last two decades, scientists have come to understand that the genetic code held within DNA represents only part of the blueprint of life. The rest comes from specific patterns of chemical tags that overlay the DNA structure, determining how tightly the DNA is packaged and how accessible certain genes are to be switched on or off.

As researchers have uncovered more and more of these "epigenetic" tags, they have begun to wonder how they are all connected. Now, research from the University of North Carolina School of Medicine has established ...

Blocking key protein could halt age-related decline in immune system, Stanford study finds

2012-10-01

STANFORD, Calif. — The older we get, the weaker our immune systems tend to become, leaving us vulnerable to infectious diseases and cancer and eroding our ability to benefit from vaccination. Now Stanford University School of Medicine scientists have found that blocking the action of a single protein whose levels in our immune cells creep steadily upward with age can restore those cells' response to a vaccine.

This discovery holds important long-term therapeutic ramifications, said Jorg Goronzy, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology and immunology and the senior author of ...

Noninvasive measurement enables use of IFP as potential biomarker for tumor aggressiveness

2012-10-01

PHILADELPHIA — Researchers validated a method of noninvasive imaging that provides valuable information about interstitial fluid pressure of solid tumors and may aid in the identification of aggressive tumors, according to the results of a study published in Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

Many malignant solid tumors generally develop a higher interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) than normal tissue. High IFP in tumors may cause a reduced uptake of chemotherapeutic agents and resistance to radiation therapy. In addition, a high ...

Mayo Clinic physicians ID reasons for high cost of cancer drugs, prescribe solutions

2012-10-01

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- A virtual monopoly held by some drug manufacturers in part because of the way treatment protocols work is among the reasons cancer drugs cost so much in the United States, according to a commentary by two Mayo Clinic physicians in the October issue of the journal Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Value-based pricing is one potential solution, they write.

VIDEO ALERT: Video of Dr. Rajkumar discussing the commentary is posted on the Mayo Clinic News Network.

Cancer care is not representative of a free-market system, and the traditional checks and balances that ...