(Press-News.org) UPTON, NY - Using a computational model they designed to incorporate detailed information about plants' interconnected metabolic processes, scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory have identified key pathways that appear to "favor" the production of either oils or proteins. The research, now published online in Plant Physiology, may point the way to new strategies to tip the balance and increase plant oil production.

The study focused on the metabolism of rapeseed, a crop grown primarily in temperate climates for the oil that accumulates in its seeds. Such plant oils are used worldwide for food, feed, and increasingly as a feedstock for the chemical industry and to produce biodiesel fuel.

"Increasing seed oil content is a major goal for the improvement of oil crops such as rapeseed," said Brookhaven biologist Jorg Schwender.

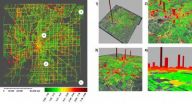

As a step toward that goal, Schwender and Brookhaven postdoctoral research associate Jordan Hay recently developed a detailed computational model incorporating 572 biochemical reactions that play a role in rapeseeds' central metabolism and/or seed oil production, as well as information on how those reactions are grouped together, are organized in subcellular compartments, and how they interact (see: http://www.bnl.gov/newsroom/news.php?a=11308). They've now used the model to identify which metabolic pathways are likely to increase in activity-and which have to decrease-to convert a "low-oil" seed into a "high-oil" seed.

Such a switch would likely be a tradeoff between oil and protein production, Schwender explained, because with limited carbon and energy resources, "the plant would 'pay' for the increased cost of making more oil by reducing its investment into seed protein."

So far, efforts based on conventional plant breeding and genetics have had very limited success in changing the typical tradeoff of storage compounds in seeds.

"Behind the production of oil and protein in seeds is a complex network of hundreds of biochemical reactions, and it is hard to determine how this network is controlled and how it could be manipulated to change the tradeoff," Schwender said.

Schwender and Hay's computational model of 572 metabolic reactions turns the problem on its head to narrow the search. Instead of manipulating each pathway one by one to see which might tip the balance from protein toward oil, the model postulates the existence of seeds with different oil and protein content to see which of the many reactions are "responsive" to changes in the oil/protein tradeoff.

"This approach allowed us to narrow down the large list of enzyme reactions to the relatively few ones that might be good candidates to be manipulated in future experimental studies," Schwender said. "Our major goal is to computationally predict the least possible number of enzymes that have most control over the tradeoff between oil and protein production."

Of the 572 reactions included in the model, the scientists identified 149 reactions as "protein-responsive" and 116 as "oil-responsive."

"In addition, the model helps us evaluate how sensitive the reactions are in a quantitative way, so we can see which of these are the 'most sensitive' reactions," Schwender said. "This allows us to identify a relatively few possible targets for future genetic manipulation to tip the balance in favor of greater seed oil production."

Some of the reactions identified by the model confirm pathways pointed out in previous research as important for oil synthesis. "But some of the reactions identified by our model have not really been implied so far to be important in the oil/protein tradeoff," Schwender said, suggesting that this could be new ground for discovery.

"These simulation tools may therefore point the way to new strategies for re-designing bioenergy crops for improved production," he concluded.

### This research was funded by the DOE Office of Science.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

One of ten national laboratories overseen and primarily funded by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Brookhaven National Laboratory conducts research in the physical, biomedical, and environmental sciences, as well as in energy technologies and national security. Brookhaven Lab also builds and operates major scientific facilities available to university, industry, and government researchers. Brookhaven is operated and managed for DOE's Office of Science by Brookhaven Science Associates, a limited-liability company founded by the Research Foundation of the State University of New York, for and on behalf of Stony Brook University, the largest academic user of Laboratory facilities; and Battelle Memorial Institute, a nonprofit, applied science and technology organization. Visit Brookhaven Lab's electronic newsroom for links, news archives, graphics, and more (http://www.bnl.gov/newsroom) or follow Brookhaven Lab on Twitter (http://twitter.com/BrookhavenLab.

Computational model IDs potential pathways to improve plant oil production

Simulated seeds help scientists explore how plants 'balance the books' between oil and protein production

2012-10-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2010 Korea bomb 'tests' probably false alarms, says study

2012-10-09

This spring, a Swedish scientist sparked international concern with a journal article saying that radioactive particles detected in 2010 showed North Korea had set off at least two small nuclear blasts--possibly in experiments designed to boost the yields of much larger bombs. Shortly after, the pot was stirred with separate claims that some intelligence agencies suspected the detonations were done in cooperation with Iran. Now, a new paper says the tests likely never took place—or that if they did, they were too tiny to have any military significance. The new report, ...

'Wonder material' graphene could revolutionize cell phones, solar panels and more

2012-10-09

WASHINGTON, October 8, 2012 — Smart phones almost as thin and flexible as paper and virtually unbreakable. Solar panels molded to cover the surface of an electric or hybrid car. Possible treatments for damaged spinal cords. It's not science fiction. Those all are possible applications of a material known as graphene. This so-called "wonder material," the world's strongest (100 times stronger than steel) and thinnest (one ounce would cover 28 football fields), is the focus of a new episode of the ChemMatters video series. The video is at www.BytesizeScience.com.

The video, ...

A DNA-made trap may explain amyloidosis aggravation

2012-10-09

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil- Amyloidosis is a group of clinical syndromes characterized by deposits of amyloid fibrils throughout the body. These fibrils are formed by aggregates of proteins that have not been properly folded. Deposits of amyloid fibrils are found in a number of diseases, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases and type-2 diabetes. The amyloid deposits can be localized, as in the brain of Alzheimer's patients, or found spread through the body, as in amyloidosis related to mutations in the transthyretin gene.

The clinical meaning of amyloid deposits ...

Child-free women feel intense pressure to have kids -- but rarely stress over it

2012-10-09

Women who choose to be permanently childfree perceive more social pressures to become mothers than other women, but feel less distress about not having kids than women who are childless from infertility or other reasons, a new national study shows.

The study, from a national survey of nearly 1,200 American women of reproductive age with no children, identified various reasons why women have no children, from medical and situational barriers to delaying pregnancy to choosing to be childfree. It sought to determine if those reasons contributed to different types of concerns ...

Caffeine may block inflammation linked to mild cognitive impairment

2012-10-09

URBANA – Recent studies have linked caffeine consumption to a reduced risk of Alzheimer's disease, and a new University of Illinois study may be able to explain how this happens.

"We have discovered a novel signal that activates the brain-based inflammation associated with neurodegenerative diseases, and caffeine appears to block its activity. This discovery may eventually lead to drugs that could reverse or inhibit mild cognitive impairment," said Gregory Freund, a professor in the U of I's College of Medicine and a member of the U of I's Division of Nutritional Sciences.

Freund's ...

New link between high-fat 'Western' diet and atherosclerosis identified

2012-10-09

New York, NY (October 8, 2012) — Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) researchers have found that a diet high in saturated fat raises levels of endothelial lipase (EL), an enzyme associated with the development of atherosclerosis, and, conversely, that a diet high in omega-3 polyunsaturated fat lowers levels of this enzyme. The findings establish a "new" link between diet and atherosclerosis and suggest a novel way to prevent cardiovascular heart disease. In addition, the research may help to explain why the type 2 diabetes drug rosiglitazone (Avandia) has been linked ...

Researchers discover regenerated lizard tails are different from originals

2012-10-09

TEMPE, Ariz. - Just because a lizard can grow back its tail, doesn't mean it will be exactly the same. A multidisciplinary team of scientists from Arizona State University and the University of Arizona examined the anatomical and microscopic make-up of regenerated lizard tails and discovered that the new tails are quite different from the original ones.

The findings are published in a pair of articles featured in a special October edition of the journal, The Anatomical Record.

"The regenerated lizard tail is not perfect replica," said Rebecca Fisher, an associate professor ...

Hospital rankings dramatically affected by calculation methods for readmissions and early deaths

2012-10-09

Hospital readmission rates and early death rates are used to rank hospital performance but there can be significant variation in their values, depending on how they are calculated, according to a new study in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

"Hospital-specific readmission rates have been reported as a quality of care indicator but no consensus exists on how these should be calculated. Our results highlight that caution is required when comparing hospital performance based on 30-day or urgent readmissions given their notable variation when methods used in their ...

Canadian C-spine rule more accurate in diagnosing important cervical spine injuries than other rules

2012-10-09

To screen for cervical spine injuries such as fractures in the emergency department, the Canadian C-spine rule appears to be more accurate compared with NEXUS, another commonly used rule, according to a study in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal). NEXUS stands for the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study.

"In the only direct comparison, the Canadian C-spine rule appeared to have better diagnostic accuracy, and it should be used over NEXUS to assess the need for cervical spine imaging," writes Dr. Chris Maher, Director, Musculoskeletal Division, ...

Study maps greenhouse gas emissions to building, street level for US cities

2012-10-09

VIDEO:

Arizona State University researchers have developed a new software system capable of estimating greenhouse gas emissions across entire urban landscapes, all the way down to roads and individual buildings. Until...

Click here for more information.

TEMPE, Ariz. - Arizona State University researchers have developed a new software system capable of estimating greenhouse gas emissions across entire urban landscapes, all the way down to roads and individual buildings. Until ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Race against time to save Alpine ice cores recording medieval mining, fires, and volcanoes

Inside the light: How invisible electric fields drive device luminescence

A folding magnetic soft sheet robot: Enabling precise targeted drug delivery via real-time reconfigurable magnetization

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for March 2026

New tools and techniques accelerate gallium oxide as next-generation power semiconductor

Researchers discover seven different types of tension

Report calls for AI toy safety standards to protect young children

VR could reduce anxiety for people undergoing medical procedures

Scan that makes prostate cancer cells glow could cut need for biopsies

Mechanochemically modified biochar creates sustainable water repellent coating and powerful oil adsorbent

New study reveals hidden role of larger pores in biochar carbon capture

Specialist resource centres linked to stronger sense of belonging and attainment for autistic pupils – but relationships matter most

Marshall University, Intermed Labs announce new neurosurgical innovation to advance deep brain stimulation technology

Preclinical study reveals new cream may prevent or slow growth of some common skin cancers

Stanley Family Foundation renews commitment to accelerate psychiatric research at Broad Institute

What happens when patients stop taking GLP-1 drugs? New Cleveland Clinic study reveals real world insights

American Meteorological Society responds to NSF regarding the future of NCAR

Beneath Great Salt Lake playa: Scientists uncover patchwork of fresh and salty groundwater

Fall prevention clinics for older adults provide a strong return on investment

People's opinions can shape how negative experiences feel

USC study reveals differences in early Alzheimer’s brain markers across diverse populations

300 million years of hidden genetic instructions shaping plant evolution revealed

High-fat diets cause gut bacteria to enter brain, Emory study finds

Teens and young adults with ADHD and substance use disorder face treatment gap

Instead of tracking wolves to prey, ravens remember — and revisit — common kill sites

Ravens don’t follow wolves to dinner – they remember where the food is

Mapping the lifelong behavior of killifish reveals an architecture of vertebrate aging

Designing for hard and brittle lithium needles may lead to safer batteries

Inside the brains of seals and sea lions with complex vocal behavior learning

Watching a lifetime in motion reveals the architecture of aging

[Press-News.org] Computational model IDs potential pathways to improve plant oil productionSimulated seeds help scientists explore how plants 'balance the books' between oil and protein production