(Press-News.org) New York, NY (October 11, 2012) — A study by scientists from the Motor Neuron Center at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) suggests that spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a genetic neuromuscular disease in infants and children, results primarily from motor circuit dysfunction, not motor neuron or muscle cell dysfunction, as is commonly thought. In a second study, the researchers identified the molecular pathway in SMA that leads to problems with motor function. Findings from the studies, conducted in fruit fly, zebrafish and mouse models of SMA, could lead to therapies for this debilitating and often fatal neuromuscular disease. Both studies were published today in the online edition of the journal Cell.

"Scientists call SMA a motor neuron disease, and there is post-mortem evidence that it does cause motor neurons to die," said Brian McCabe, PhD, assistant professor of pathology and cell biology and of neuroscience in the Motor Neuron Center, who led the first study. "However, it was not clear whether the death of motor neurons is a cause of the disease or an effect. Our findings in the fruit fly SMA model show that the disease originates in other motor circuit neurons, which then causes motor neurons to malfunction."

In motor circuits, which coordinate muscle movement, specialized sensory neurons called proprioceptive neurons pick up and relay information to the spinal cord and brain about the body's position in space. The central nervous system then processes and relays the signals, including via interneurons, to motor neurons, which in turn stimulate muscle movement.

"To our knowledge, this is the first clear demonstration in a model organism that defects in the function of a neuronal circuit are the cause of a neurological disease," added Dr. McCabe.

SMA is a hereditary neuromuscular disease characterized by muscle atrophy and weakness. The disease is caused by defects in a gene called SMN1 (survival motor neuron 1), which encodes the SMN protein. There are several forms of SMA, distinguished by time of onset and clinical severity. The most severe form, Type 1, appears before six months of age and generally results in death by age two. In milder forms, symptoms may not appear until much later in childhood or even in early adulthood. There is no treatment for SMA, which is estimated to affect as many as 10,000 to 25,000 children and adults in the United States and is the leading genetic cause of death in infants.

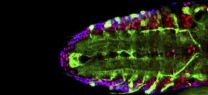

To study the cause of SMA, the researchers worked with fruit flies that had been genetically altered so that every cell had a defective copy of the SMN1 gene. The flies' cells contained low levels of SMN protein, resulting in reduced muscle size and motor function, much as in humans with SMA. When fully functional copies of SMN1 were introduced into the flies' motor neurons or muscle cells, the cell types previously thought to be affected, the flies unexpectedly showed no improvement. Only when SMN1 was returned to other motor circuit neurons — in particular, proprioceptive neurons and interneurons — were muscle size and motor function restored.

In further experiments, the researchers demonstrated that in fruit flies with defective SMN1, proprioceptive neurons and interneurons do not produce enough neurotransmitters. When the flies' potassium channels were genetically blocked — thereby increasing neurotransmitter output — muscle size and motor function improved. The same effect was seen when the flies were given drugs that block potassium channels, suggesting that this class of drugs might help patients with SMA.

Supported by these findings, in July, the SMA Clinical Research Center at CUMC launched a clinical trial of a potassium channel blocker called dalfampridine (Ampyra) for the treatment of patients with SMA. The study will assess whether the drug improves walking ability and endurance in adults with SMA Type 3, compared with placebo. Claudia A. Chiriboga, MD, MPH, associate professor of Clinical Neurology at CUMC, is the lead clinical investigator. Ampyra was approved by the FDA for the treatment of patients with multiple sclerosis in 2010.

"This drug is unlikely to be a cure for SMA, but we hope it will benefit patient symptoms," said Dr. McCabe. "Other compounds at various stages of development hold promise to fix the underlying molecular problem."

The second study, led jointly by Livio Pellizzoni, PhD, assistant professor of Pathology and Cell Biology in the Motor Neuron Center, and Dr. McCabe, sought to determine how the loss of SMN protein — which is expressed in all cells — leads to the selective disruption of motor circuits. Working with models of SMA in mammalian cells, fruit flies, zebrafish, and mice, the researchers demonstrated that SMN1 deficiency disrupts a fundamental cellular process known as RNA splicing with detrimental effects on the expression of a subset of genes that contain a rare type of intron. (In the process of RNA splicing, parts of RNA called introns are removed so a gene can be translated into protein.) By studying the function of this group of genes affected by the loss of SMN1, the researchers discovered a novel gene — which they named stasimon — that is critically required for motor circuit activity in vivo. They further showed that restoring expression of stasimon was alone sufficient to correct key aspects of motor dysfunction in both invertebrate and vertebrate models of SMA.

"What is intriguing about SMA is that mutations in the disease gene SMN1 reduce its expression in all cells, yet patients get this specific disease of the motor system. The reason for this has been a longstanding enigma in the SMA field," said Dr. Pellizzoni. "Our findings provide the first explanation at the molecular level as to how this can happen. We show a direct link from the loss of the SMN1 gene to defective splicing of a critical neuronal gene to motor circuit dysfunction, establishing SMA as a disease of RNA splicing. By linking SMN-dependent splicing events to motor circuit function, our work has implications for understanding the pathogenic mechanisms not only of SMA, but also of other neurological disorders," said Dr. Pellizzoni.

"The potential added value of our study is that we've identified a novel gene that is targeted by the disease protein. When disrupted, this gene — stasimon — appears to contribute to the development of SMA in model organisms. The implication is that this gene and the pathway in which it functions might be new candidate therapeutic targets," Dr. Pellizzoni added.

INFORMATION:

The first paper is titled, "SMN is required for sensory-motor circuit function in Drosophila." Contributors are Wendy L. Imlach, Erin S. Beck, Ben Jiwon Choi, Francesco Lotti, Livio Pellizzoni, and Brian D. McCabe, all at CUMC. The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants T32 GM07367, 5T32HL08774, and R01NS069601; Department of Defense grants DoD-W81XWH-08-1-0009 and DoD-W81XWH-11-1-0753; and grants from the SMA foundation and the Columbia Center for Motor Neuron Biology and Disease.

The second paper is titled, "A SMN-Dependent U12 Splicing Event Essential for Motor Circuit Function." Contributors are Francesco Lotti (CUMC), Wendy L. Imlach (CUMC), Luciano Saieva (CUMC), Erin S. Beck (CUMC), Le T. Hao (Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio), Darrick K. Li (CUMC), Wei Jiao (CUMC), George Z. Mentis (CUMC), Christine E. Beattie (Ohio State University), Brian D. McCabe (CUMC), and Livio Pellizzoni (CUMC). The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01NS069601, R21NS077038, and R01NS050414; Department of Defense grants W81XWH-08-1-0009, W81XWH-11-1-0753, and W81XWH-11-1-0689; and grants from the SMA Foundation, the Muscular Dystrophy Association - USA, Families of SMA, and the Columbia Center for Motor Neuron Biology and Disease. The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

The Center for Motor Neuron Biology and Disease (MNC) at Columbia University Medical Center brings together 40 basic and clinical research groups working on different aspects of motor neuron biology and disease, including spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). MNC members are housed in various departments throughout the Columbia University and Columbia University Medical Center campuses, to draw upon the unique range and depth of expertise in this multidisciplinary field at Columbia. MNC researchers and clinicians study basic motor neuron biology in parallel with disease models and clinical trials in ALS and SMA. For more information about MNC visit:

www.ColumbiaMNC.org

For further information visit: http://pathology.columbia.edu/

Columbia University Medical Center provides international leadership in basic, pre-clinical and clinical research, in medical and health sciences education, and in patient care. The medical center trains future leaders and includes the dedicated work of many physicians, scientists, public health professionals, dentists, and nurses at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, the Mailman School of Public Health, the College of Dental Medicine, the School of Nursing, the biomedical departments of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and allied research centers and institutions. Established in 1767, Columbia's College of Physicians and Surgeons was the first institution in the country to grant the M.D. degree and is among the most selective medical schools in the country. Columbia University Medical Center is home to the largest medical research enterprise in New York City and State and one of the largest in the United States.

Novel mechanisms underlying major childhood neuromuscular disease identified

Findings point to possible treatments for the leading genetic cause of death in infants

2012-10-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Diverse intestinal viruses may play a role in AIDS progression

2012-10-11

In monkeys and humans with AIDS, damage to the gastrointestinal tract is common, contributing to activation of the immune system, progressive immune deficiency, and ultimately advanced AIDS. How this gastric damage occurs has remained a mystery, but now researchers reporting in the Cell Press journal Cell provide new clues, implicating the presence of potentially pathogenic virus species other than the main virus that causes AIDS. The findings could provide an opportunity to explain and eventually intervene in the processes that lead to AIDS progression.

To investigate ...

Stopping the itch -- new clues into how to treat eczema

2012-10-11

More than 15% of children suffer with eczema, or atopic dermatitis, an inflammatory skin disease that in some cases can be debilitating and disfiguring. Researchers reporting in the October issue of Immunity have discovered a potential new target for the condition, demonstrating that by blocking it, they can lessen the disease in mice.

In eczema, immune T cells invade the skin and secrete factors that drive an allergic response, making the skin itch. Dr. Raif Geha, of Boston Children's Hospital, and his collaborators now show that scratching the skin precipitates the ...

New report calls for global efforts to prevent fragility fractures due to osteoporosis

2012-10-11

Today, the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) released a new report, revealing approximately 80 percent of patients treated in clinics or hospitals following a fracture are not screened for osteoporosis or risk of future falls. Left untreated, these patients are at high risk of suffering secondary fractures and facing a future of pain, disfigurement, long-term disability and even early death.

The report 'Capture the Fracture – A global campaign to break the fragility fracture cycle' calls for concerted worldwide efforts to stop secondary fractures due to osteoporosis ...

Target for obesity drugs comes into focus

2012-10-11

ANN ARBOR—Researchers at the University of Michigan have determined how the hormone leptin, an important regulator of metabolism and body weight, interacts with a key receptor in the brain.

Leptin is a hormone secreted by fat tissue that has been of interest for researchers in obesity and Type 2 diabetes since it was discovered in 1995. Like insulin, leptin is part of a regulatory network that controls intake and expenditure of energy in the body, and a lack of leptin or resistance to it has been linked to obesity in people.

Although there can be several complex reasons ...

Large international study finds 21 genes tied to cholesterol levels

2012-10-11

In the largest-ever genetic study of cholesterol and other blood lipids, an international consortium has identified 21 new gene variants associated with risks of heart disease and metabolic disorders. The findings expand the list of potential targets for drugs and other treatments for lipid-related cardiovascular disease, a leading global cause of death and disability.

The International IBC Lipid Genetics Consortium used the Cardiochip, a gene analysis tool invented by Brendan J. Keating, Ph.D., a scientist at the Center for Applied Genomics at The Children's Hospital ...

Feeding the Schwanns: New technique could bring cell therapy for nerve damage a step closer

2012-10-11

A new way to grow cells vital for nerve repair, developed by researchers from the University of Sheffield, could be a vital step for use in patients with severe nerve damage, including spinal injury (1).

Schwann cells are known to boost and amplify nerve growth in animal models, but their clinical use has been held back because they are difficult, time-consuming and costly to culture.

The Sheffield team, led by Professor John Haycock, has developed a new technique with adult rat tissue which overcomes all these problems, producing Schwann cells in less than half the time ...

New tool determines leukemia cells' 'readiness to die,' may guide clinical care

2012-10-11

Researchers at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute have developed a novel method for determining how ready acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells are to die, a discovery that may help cancer specialists to choose treatments option more effectively for their patients who have AML.

In a study published in the Oct. 12 issue of the journal Cell, the researchers report that their findings may lead to improved tests to predict which patients successfully treated for AML can continue in remission with standard chemotherapy alone, and which patients are likely to relapse despite ...

Nearby super-Earth likely a diamond planet

2012-10-11

New Haven, Conn. — New research led by Yale University scientists suggests that a rocky planet twice Earth's size orbiting a nearby star is a diamond planet.

"This is our first glimpse of a rocky world with a fundamentally different chemistry from Earth," said lead researcher Nikku Madhusudhan, a Yale postdoctoral researcher in physics and astronomy. "The surface of this planet is likely covered in graphite and diamond rather than water and granite."

The paper reporting the findings has been accepted for publication in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The ...

A new cave-dwelling reef coral discovered in the Indo-Pacific

2012-10-11

Coral specialist Dr. Bert W. Hoeksema of Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, The Netherlands, recently published the description of a new coral species that lives on the ceilings of caves in Indo-Pacific coral reefs. It differs from its closest relatives by its small polyp size and by the absence of symbiotic algae, so-called zooxanthellae. Its distribution range overlaps with the Coral Triangle, an area that is famous for its high marine species richness. Marine zoologists of Naturalis visit this area frequently to explore its marine biodiversity.

Reef corals in ...

How food marketers can help consumers eat better while improving their bottom line

2012-10-11

Food marketers are masters at getting people to crave and consume the foods that they promote. In this study authors Dr. Brian Wansink, co-director of the Cornell University Center for Behavioral Economics in Child Nutrition and Professor of Marketing and Dr. Pierre Chandon, professor of Marketing at the leading French graduate school of business, INSEAD challenge popular assumptions that link food marketing and obesity. Their findings presented last weekend at the Association for Consumer Research Conference in Vancouver, Canada point to ways in which smart food marketers ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

[Press-News.org] Novel mechanisms underlying major childhood neuromuscular disease identifiedFindings point to possible treatments for the leading genetic cause of death in infants