(Press-News.org) WESTMINSTER, CO (October 10, 2012)—Numerous studies have shown that female athletes are more likely to get knee injuries, especially anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears and chronic pain, than their male counterparts. While previous research has focused on biomechanical differences as the main source of these problems, a new study suggests another distinction that could play a role: changes across the menstrual cycle in nerves that control muscle activity. The finding may eventually lead to new ways to prevent knee problems in female athletes.

Matthew Tenan, Yi-Ling Peng, and Lisa Griffin, all of the University of Texas-Austin, and Anthony Hackney, of the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, measured the activity of motor units—nerve fibers and the muscles they control—around the knees of female volunteers at various points of their menstrual cycles. They found that these bundles had firing rates that were significantly higher in the late luteal phase, about a week before a woman's next period, compared to earlier in the menstrual cycle. This difference in firing rate could affect the stability of the joint, potentially affecting its susceptibility to injury.

Their poster presentation entitled, "Maximal Force and Motor Unit Recruitment Patterns are Altered Across the Human Menstrual Cycle," will be discussed at The Integrative Biology of Exercise VI meeting being held October 10-13 at the Westin Westminster Hotel in Westminster, CO. This popular meeting is a collaborative effort between the American Physiological Society, the American College of Sports Medicine and the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. The conference is supported in part by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, an institute of the National Institutes of Health, GlaxoSmithKline, Inc., Stealth Peptides, Inc., and Seahorse Biosciences. The full program is online at http://bit.ly/OrMFtN.

More Than Biomechanics?

Differences in muscle structure around female athletes' knees have typically gotten the blame for disparities in knee injuries between the sexes, especially for athletes who play sports such as soccer or basketball that involve a substantial amount of knee twisting, turning, and jerking, says study leader Tenan. However, he adds, it's been unclear whether other factors, such as differences in motor unit firing patterns, might also play a part. Since female athletes' hormones fluctuate across the menstrual cycle, Tenan and his colleagues decided to investigate whether these changes affect motor unit activity.

Working with seven female volunteers, all between the ages of 19 and 35, the researchers asked these study participants to chart their menstrual cycles using basal body temperature. This method involves taking body temperature every morning upon waking over the course of the menstrual cycle. Because temperature increases slightly after ovulation (the luteal phase), then dips to pre-ovulation temperatures just before the start of a new cycle (the follicular phase), it's possible to track where each volunteer was in her menstrual cycle on any given day.

The researchers also asked each volunteer to visit their facility five different times at various points of the menstrual cycle. At each visit, they inserted a fine wire electrode, no thicker than a human hair, into two muscles around one of each of the volunteers' knees. The women then did knee extensions while the researchers used these electrodes to measure the activity of motor units in those muscles.

Avoiding Injury

Results showed that motor unit firing patterns varied significantly across the menstrual cycle. Most notably, Tenan and his colleagues found that the rate of firing jumped in the late luteal phase compared to rates earlier in the cycle. Though they're not sure whether these results coincide with a difference in knee injury rates at different points in the menstrual cycle—a topic for future research. Tenan notes that changes in motor unit activity could make women more vulnerable to injury in general.

"Our results suggest that muscle activation patterns are altered by the menstrual cycle," he says. "These alterations could lead to changes in rates of injury."

The findings, he adds, could prompt a closer look at the neuroendocrine system in addition to biomechanics as a possible cause for knee injuries in female athletes—potentially leading to new ways to help female athletes avoid these problems.

### About the American Physiological Society (APS)

The American Physiological Society (APS) is a nonprofit organization devoted to fostering education, scientific research, and dissemination of information in the physiological sciences. The Society was founded in 1887 and today has more than 11,000 members. APS publishes 13 scholarly, peer-reviewed journals covering specialized aspects of physiology.

NOTE TO EDITORS: To receive a copy of the abstract or schedule an interview with a member of the research team, please contact Donna Krupa at DKrupa@the-aps.org, 301.634.7209 (office) or 703.967.2751 (cell).

Nerve and muscle activity vary across menstrual cycle

Finding may help explain higher rates of knee injuries in female athletes

2012-10-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

UT study: Natural playgrounds more beneficial to children, inspire more play

2012-10-12

KNOXVILLE—Children who play on playgrounds that incorporate natural elements like logs and flowers tend to be more active than those who play on traditional playgrounds with metal and brightly colored equipment, according to a recent study from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

They also appear to use their imagination more, according to the report.

The study, which examined changes in physical activity levels and patterns in young children exposed to both traditional and natural playgrounds, is among the first of its kind in the United States, according to Dawn ...

Terrorism risk greatest for subway/rail commuters, says MIT paper at INFORMS conference

2012-10-12

Despite homeland security improvements since September 11, 2001, subway and rail commuters face higher risks of falling victim to terrorists and mass violence than frequent flyers or those engaged in virtually any other activity. And while successful criminal and terrorist acts against aviation have fallen sharply, those against subways and commuter trains have surged. These are among the findings of a new study by Arnold Barnett, George Eastman Professor of Management Science at MIT's Sloan School of Management, who will deliver a presentation titled "Has Terror Gone to ...

Antibiotic resistance a growing concern with urinary tract infection

2012-10-12

CORVALLIS, Ore. – As a result of concerns about antibiotic resistance, doctors in the United States are increasingly prescribing newer, more costly and more powerful antibiotics to treat urinary tract infections, one of the most common illnesses in women.

New research at Oregon State University suggests that the more powerful medications are used more frequently than necessary, and they recommend that doctors and patients discuss the issues involved with antibiotic therapy – and only use the stronger drugs if really neeeded.

Urinary tract infections are some of the ...

Earth sunblock only needed if planet warms easily

2012-10-12

RICHLAND, Wash. -- An increasing number of scientists are studying ways to temporarily reduce the amount of sunlight reaching the earth to potentially stave off some of the worst effects of climate change. Because these sunlight reduction methods would only temporarily reduce temperatures, do nothing for the health of the oceans and affect different regions unevenly, researchers do not see it as a permanent fix. Most theoretical studies have examined this strategy by itself, in the absence of looking at simultaneous attempts to reduce emissions.

Now, a new computer analysis ...

Engineered flies spill secret of seizures

2012-10-12

VIDEO:

Fruit flies with a genetic tendency toward fever-induced seizures (top) are the first to stop moving freely and are swept aside by a gentle air current as the temperature rises....

Click here for more information.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In a newly reported set of experiments that show the value of a particularly precise but difficult genetic engineering technique, researchers at Brown University and the University of California–Irvine have created a Drosophila ...

Researchers work across fields to uncover information about hadrosaur teeth

2012-10-12

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — An unusual collaboration between researchers in two disparate fields resulted in a new discovery about the teeth of 65-million-year-old dinosaurs.

With the help of University of Florida mechanical engineering professor W. Gregory Sawyer and UF postdoctoral researcher Brandon Krick, Florida State University paleobiologist Gregory Erickson determined the teeth of hadrosaurs — an herbivore from the late Cretaceous period — had six tissues in their teeth instead of two. The results were published in the journal Science Oct. 5.

"When something has been ...

Notre Dame researcher helps make Sudoku puzzles less puzzling

2012-10-12

For anyone who has ever struggled while attempting to solve a Sudoku puzzle, University of Notre Dame researcher Zoltan Toroczkai and Notre Dame postdoctoral researcher Maria Ercsey-Ravaz are riding to the rescue. They can not only explain why some Sudoku puzzles are harder than others, they have also developed a mathematical algorithm that solves Sudoku puzzles very quickly, without any guessing or backtracking.

Toroczkai and Ravaz of Romania's Babes-Boylai University began studying Sudoku as part of their research into the theory of optimization and computational complexity. ...

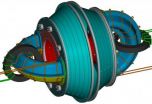

Mug handles could help hot plasma give lower-cost, controllable fusion energy

2012-10-12

Researchers around the world are working on an efficient, reliable way to contain the plasma used in fusion reactors, potentially bringing down the cost of this promising but technically elusive energy source. A new finding from the University of Washington could help contain and stabilize the plasma using as little as 1 percent of the energy required by current methods.

"All of a sudden the current energy goes from being almost too much to almost negligible," said lead author Thomas Jarboe, a UW professor of aeronautics and astronautics. He presents the findings this ...

More than just 'zoning out' -- Exploring the cognitive processes behind mind wandering

2012-10-12

It happens innocently enough: One minute you're sitting at your desk, working on a report, and the next minute you're thinking about how you probably need to do laundry and that you want to try the new restaurant down the street. Mind wandering is a frequent and common occurrence. And while mind wandering in certain situations – in class, for example – can be counterproductive, some research suggests that mind wandering isn't necessarily a bad thing.

New research published in the journals of the Association for Psychological Science explores mind wandering in various ...

Duke Medicine news -- Anti-cancer drug fights immune reaction in some infants with Pompe disease

2012-10-12

DURHAM, N.C. – Adding a third anti-cancer agent to a current drug cocktail appears to have contributed to dramatic improvement in three infants with the most severe form of Pompe disease -- a rare, often-fatal genetic disorder characterized by low or no production of an enzyme crucial to survival.

Duke researchers previously pioneered the development of the first effective treatment for Pompe disease via enzyme replacement therapy (ERT). ERT relies on a manufactured enzyme/protein to act as a substitute for the enzyme known to be lacking in patients with a particular disease. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

[Press-News.org] Nerve and muscle activity vary across menstrual cycleFinding may help explain higher rates of knee injuries in female athletes