(Press-News.org) Researchers from Johns Hopkins and Northwestern universities have discovered how to control the shape of nanoparticles that move DNA through the body and have shown that the shapes of these carriers may make a big difference in how well they work in treating cancer and other diseases.

This study, to be published in the Oct. 12 online edition of the journal Advanced Materials, is also noteworthy because this gene therapy technique does not use a virus to carry DNA into cells. Some gene therapy efforts that rely on viruses have posed health risks.

"These nanoparticles could become a safer and more effective delivery vehicle for gene therapy, targeting genetic diseases, cancer and other illnesses that can be treated with gene medicine," said Hai-Quan Mao, an associate professor of materials science and engineering in Johns Hopkins' Whiting School of Engineering.

Mao, co-corresponding author of the Advanced Materials article, has been developing nonviral nanoparticles for gene therapy for a decade. His approach involves compressing healthy snippets of DNA within protective polymer coatings. The particles are designed to deliver their genetic payload only after they have moved through the bloodstream and entered the target cells. Within the cells, the polymer degrades and releases DNA. Using this DNA as a template, the cells can produce functional proteins that combat disease.

A major advance in this work is that Mao and his colleagues reported that they were able to "tune" these particles in three shapes, resembling rods, worms and spheres, which mimic the shapes and sizes of viral particles. "We could observe these shapes in the lab, but we did not fully understand why they assumed these shapes and how to control the process well," Mao said. These questions were important because the DNA delivery system he envisions may require specific, uniform shapes.

To solve this problem, Mao sought help about three years ago from colleagues at Northwestern. While Mao works in a traditional wet lab, the Northwestern researchers are experts in conducting similar experiments with powerful computer models.

Erik Luijten, associate professor of materials science and engineering and of applied mathematics at Northwestern's McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science and co-corresponding author of the paper, led the computational analysis of the findings to determine why the nanoparticles formed into different shapes.

"Our computer simulations and theoretical model have provided a mechanistic understanding, identifying what is responsible for this shape change," Luijten said. "We now can predict precisely how to choose the nanoparticle components if one wants to obtain a certain shape."

The use of computer models allowed Luijten's team to mimic traditional lab experiments at a far faster pace. These molecular dynamic simulations were performed on Quest, Northwestern's high-performance computing system. The computations were so complex that some of them required 96 computer processors working simultaneously for one month.

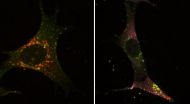

In their paper, the researchers also wanted to show the importance of particle shapes in delivering gene therapy. Team members conducted animal tests, all using the same particle materials and the same DNA. The only difference was in the shape of the particles: rods, worms and spheres.

"The worm-shaped particles resulted in 1,600 times more gene expression in the liver cells than the other shapes," Mao said. "This means that producing nanoparticles in this particular shape could be the more efficient way to deliver gene therapy to these cells."

The particle shapes used in this research are formed by packaging the DNA with polymers and exposing them to various dilutions of an organic solvent. DNA's aversion to the solvent, with the help of the team's designed polymer, causes the nanoparticles to contract into a certain shape with a "shield" around the genetic material to protect it from being cleared by immune cells.

INFORMATION:

Lead authors of the Advanced Materials paper are Wei Qu, a graduate student in Luijten's research group at Northwestern, and Xuan Jian, who was a doctoral student in Mao's lab. Along with Mao and Luijten, the remaining co-authors of the paper, all from Johns Hopkins, are Deng Pan, who worked on the project as an undergraduate; Yong Ren, a postdoctoral fellow; John-Michael Williford, a biomedical engineering doctoral student; and Honggang Cui, an assistant professor in the department of chemical and biomolecular engineering.

Scientists discover that shape matters in DNA nanoparticle therapy

Particles could become a safer, more effective delivery vehicle for gene therapy

2012-10-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Report -- illegal hunting and trade of wildlife in savanna Africa may cause conservation crisis

2012-10-12

New York, NY and Hyderabad (India) – A new report published today by Panthera confirms that widespread illegal hunting and the bushmeat trade occur more frequently and with greater impact on wildlife populations in the Southern and Eastern savannas of Africa than previously thought, and if unaddressed could potentially cause a 'conservation crisis.' The report challenges previously held beliefs of the impact of illegal bushmeat hunting and trade in Africa with new data from experts.

While the bushmeat trade has long been recognized as a severe threat to the food resources ...

New weapons detail reveals true depth of Cuban Missile Crisis

2012-10-12

The Cuban Missile Crisis took place 50 years ago this October, when US and Soviet leaders pulled back from the very brink of nuclear war. This was the closest the world has come to nuclear war, but exactly how close has been a matter of some speculation. The conflict, itself, has been analyzed and interpreted, but the number and types of nuclear weapons that were operational have not. According to fresh analysis available today in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, published by SAGE, senior experts calculate the nature of weapons capabilities on both sides, and write ...

GMES for Europe

2012-10-12

The potential of GMES for crisis management and environmental monitoring is highlighted in a new publication with users demonstrating the importance of Earth observation data to European regions.

The joint ESA-NEREUS (Network of European Regions Using Space Technologies) publication is a collection of articles that provide insight into how the Global Monitoring for Environment and Security (GMES) programme is being used in new applications and services across Europe.

The articles, prepared by regional end-users, research institutes and industry providers from 17 different ...

Development of 2 tests for rapid diagnosis of resistance to antibiotics

2012-10-12

With their excellent sensitivity and specificity, the use of these extremely efficient tests on a world-wide scale would allow us to adapt antibiotic treatments to the individual's needs and to be more successful in controlling antibiotic resistance, particularly in hospitals. These works were published in September in two international reviews:

Emerging Infectious diseases and The Journal of Clinical Microbiology.

These diagnostic tests will allow rapid identification of certain bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics and hence:

Allow us to better adapt the treatment ...

Scientists identify trigger for explosive volcanic eruptions

2012-10-12

Scientists from the University of Southampton have identified a repeating trigger for the largest explosive volcanic eruptions on Earth.

The Las Cañadas volcanic caldera on Tenerife, in the Canary Islands, has generated at least eight major eruptions during the last 700,000 years. These catastrophic events have resulted in eruption columns of over 25km high and expelled widespread pyroclastic material over 130km. By comparison, even the smallest of these eruptions expelled over 25 times more material than the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull, Iceland.

By analysing ...

The body's own recycling system

2012-10-12

Almost everything that happens inside a cell, including autophagy, is tightly regulated on a biochemical level. Like that, the cell makes sure that processes only take place when they are needed and that they are shut off when the need has expired. "Inside the cell, there exists a network of molecules. Between them, information is constantly being exchanged," says Schmitz, head of the research group "Systems-oriented Immunology and Inflammation Research" at HZI, who also holds a chair at the Otto von Guericke University in Magdeburg. "In a way, it looks like a big city ...

The worst noises in the world: Why we recoil at unpleasant sounds

2012-10-12

In a study published in the Journal of Neuroscience and funded by the Wellcome Trust, Newcastle University scientists reveal the interaction between the region of the brain that processes sound, the auditory cortex, and the amygdala, which is active in the processing of negative emotions when we hear unpleasant sounds.

Brain imaging has shown that when we hear an unpleasant noise the amygdala modulates the response of the auditory cortex heightening activity and provoking our negative reaction.

"It appears there is something very primitive kicking in," says Dr Sukhbinder ...

Kidney grafts function longer in Europe than in the United States

2012-10-12

Kidney transplants performed in Europe are considerably more successful in the long run than those performed in the United States. While the one-year survival rate is 90% in both Europe and the United States, after five years, 77% of the donor kidneys in Europe still function, while in the United States, this rate among white Americans is only 71%. After ten years, graft survival for the two groups is 56% versus 46%, respectively. The lower survival rates compared to Europe also apply to Hispanic Americans, in whom 48% of the transplanted kidneys still function after ten ...

Neuroscientists from Louisiana Tech University to present at international conference

2012-10-12

RUSTON, La. – Dr. Mark DeCoster, the James E. Wyche III Endowed Professor in Biomedical Engineering at Louisiana Tech University, will lead a team of Louisiana Tech neuroscientists in presenting a lecture at the Society for Neuroscience's (SfN) annual meeting, October 15 in New Orleans.

The lecture titled, "Randomization of submaximal glutamate stimulus to interpret astrocyte effect on calcium dynamics," will be featured as part of Neuroscience 2012 – SfN's annual meeting that provides the world's largest forum for neuroscientists to debut research and network with colleagues ...

'Invisibility' could be a key to better electronics

2012-10-12

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — A new approach that allows objects to become "invisible" has now been applied to an entirely different area: letting particles "hide" from passing electrons, which could lead to more efficient thermoelectric devices and new kinds of electronics.

The concept — developed by MIT graduate student Bolin Liao, former postdoc Mona Zebarjadi (now an assistant professor at Rutgers University), research scientist Keivan Esfarjani, and mechanical engineering professor Gang Chen — is described in a paper in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Normally, electrons ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

Anxiety, depression, and care barriers in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities

[Press-News.org] Scientists discover that shape matters in DNA nanoparticle therapyParticles could become a safer, more effective delivery vehicle for gene therapy