(Press-News.org) The unexpected survival of embryonic neurons transplanted into the brains of newborn mice in a series of experiments at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) raises hope for the possibility of using neuronal transplantation to treat diseases like Alzheimer's, epilepsy, Huntington's, Parkinson's and schizophrenia.

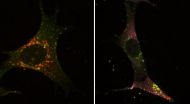

The experiments, described this week in the journal Nature, were not designed to test whether embryonic neuron transplants could effectively treat any specific disease. But they provide a proof-of-principle that GABA-secreting interneurons, a type of brain cell linked to many different neurological disorders, can be added in significant numbers into the brain and can survive without affecting the population of endogenous interneurons.

The survival of these cells after transplantation in numbers far greater than expected came as a shock to the team, which was led by UCSF professor Arturo Alvarez-Buylla, PhD, and former UCSF graduate student Derek Southwell, MD, PhD.

The prevailing theory held that the survival of developing neurons is something like a game of musical chairs. The brain has limited capacity for these cells, forcing them to compete with each other for the few available slots. Only those that find a place to "sit" (and receive survival signals derived from other cell types) will survive when the music stops. The rest die a withering death.

Based on this theory, the UCSF team had expected only a fixed and small number of transplanted embryonic interneurons would survive in the brains of older recipient mice, regardless of how many they transplanted. What they found was very different: Regardless of how many they transplanted, a consistent percentage always survived.

"[This constant rate of survival] suggests that these cells, which other collaborative studies have shown have great therapeutic promise, can be added to cortex in significant numbers," said Alvarez-Buylla, who is the Heather and Melanie Muss Professor of Neurological Surgery and a member of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regeneration Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCSF.

Past work at UCSF and elsewhere has shown that transplanting these cells can create a new critical period of plasticity in the recipient brain, reduce seizures in animal models of epilepsy, and reduce Parkinson's-like movement disorders in laboratory rats. The activity of these cells is often disrupted in Alzheimer's disease, and their number is altered in the brains of people with schizophrenia. When transplanted into the spinal cord, they also help decrease pain sensation.

In the current study, the UCSF team found that as they altered the number of cells they transplanted, a constant proportion of these cells survived – rather than a constant number – suggesting that a fraction of the cells is destined to die by cell-autonomous mechanisms or that a survival factor is secreted by the inhibitory neurons themselves. The work shows that these interneurons may be transplanted in far greater numbers than previously thought – an observation that could have important implications for the use of these cells to correct defects in the excitatory/inhibitory valance in the disease brain.

Survival of Cells Depends on Unknown "Signals

GABAergic interneurons are essential for brain function because they balance the action of "excitatory" neurons in the cerebral cortex by producing inhibitory signals. Diseases like epilepsy, Alzheimer's, Huntington's, Parkinson's and schizophrenia are all variously linked to disruptions in this excitatory/inhibitory balance, and problems with the GABAergic interneurons have been documented in all these diseases.

These GABAergic interneurons are not born in the cerebral cortex – the part of the brain where they will ultimately become incorporated into functional circuits. Instead, they are created in a distant part of the developing brain and then migrate to their final destination. For decades, scientists have not known how the appropriate number of these interneurons is determined, how many are formed, when they die and how many survive after reaching the cerebral cortex. The recent publication addresses some of these unknowns, but also revealed an unexpected observation.

It is generally believed that neuronal numbers are determined by availability of survival signals provided by other target cells. This idea, generally known as the "neurotrophic hypothesis," is based on Nobel Prize-winning experiments in the 1940s showing how the survival of developing neurons in the spinal cord and peripheral nervous system is determined. That work showed that only the nerve fibers that could correctly connect to targets outside the nervous system would survive and that these targets produced a protein called nerve growth factor responsible for keeping the nerves alive.

For many years, the neurotrophic hypothesis has dominated ideas of how and why cells in the brain live and die. "The neurotrophic hypothesis has since been assumed to apply to all types neurons and all areas of the nervous system," said Southwell.

The assumption was that once the GABAergic interneurons winded their way to the right part of the brain, only those that melded with the other neurons already there would be protected by a protein or some other factor to stay alive. Instead, the survival of the transplanted interneurons was determined in a manner that was independent from competition for survival signals produced by other types of cells in the recipients.

While the new experiments do not overthrow this theory as it applies to how nerves outside the brain connect to their targets, they suggest there may be something else going on with GABAergic interneurons.

### The article, "Intrinsically determined cell death of developing cortical interneurons" by Derek G. Southwell, Mercedes F. Paredes, Rui P. Galvao, Daniel L. Jones, Robert C. Froemke, Joy Y. Sebe, Clara Alfaro-Cervello, Yunshuo Tang, Jose M. Garcia-Verdugo, John L. Rubenstein, Scott C. Baraban and Arturo Alvarez-Buylla is published in the journal Nature on October 7, 2012. See: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature11523

This work was funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the John G. Bowes Research Fund, the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, and the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke, one of the National Institutes of Health, through grant #R01 NS071785 and # R01 NS048528.

UCSF is a leading university dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care.

Follow UCSF

UCSF.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | Twitter.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

Transplantation of embryonic neurons raises hope for treating brain diseases

UCSF experiments challenge prevailing theory for the basis of cell death in the developing brain

2012-10-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

White construction workers in Illinois get higher workers' comp settlements: Study

2012-10-12

White non-Hispanic construction workers are awarded higher workers' compensation settlements in Illinois than Hispanic or black construction workers with similar injuries and disabilities, according to researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health.

The disparity amounted to approximately $6,000 more for white non-Hispanic claimants compared to minority workers in the same industry, says Lee Friedman, assistant professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at UIC and lead author of the study, which was published in the October ...

Documented decrease in frequency of Hawaii's northeast trade winds

2012-10-12

Scientists at University of Hawaii at Manoa (UHM) have observed a decrease in the frequency of northeast trade winds and an increase in eastern trade winds over the past nearly four decades, according to a recent study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research. For example, northeast trade wind days, which occurred 291 days per year 37 years ago at the Honolulu International Airport, now only occur 210 days per year.

Jessica Garza, a Meteorology Graduate Assistant at the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST) at UHM; Pao-Shin Chu, Meteorology ...

Surgery or radiation, not monitoring, most often sought for low-risk prostate cancer, Mayo finds

2012-10-12

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- Few physicians recommend active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer rather than pursuing surgery or radiation, according to a Mayo Clinic study being presented at the North Central Section of the American Urological Association's annual meeting Oct. 10 in Chicago. Mayo Clinic urologists also are discussing findings on enlarged prostates, bladder cancer and other research and will be available to provide expert comment to journalists on others' studies.

Mayo studies being presented, and their embargo dates and times, include:

Active Surveillance ...

Scientists discover that shape matters in DNA nanoparticle therapy

2012-10-12

Researchers from Johns Hopkins and Northwestern universities have discovered how to control the shape of nanoparticles that move DNA through the body and have shown that the shapes of these carriers may make a big difference in how well they work in treating cancer and other diseases.

This study, to be published in the Oct. 12 online edition of the journal Advanced Materials, is also noteworthy because this gene therapy technique does not use a virus to carry DNA into cells. Some gene therapy efforts that rely on viruses have posed health risks.

"These nanoparticles ...

Report -- illegal hunting and trade of wildlife in savanna Africa may cause conservation crisis

2012-10-12

New York, NY and Hyderabad (India) – A new report published today by Panthera confirms that widespread illegal hunting and the bushmeat trade occur more frequently and with greater impact on wildlife populations in the Southern and Eastern savannas of Africa than previously thought, and if unaddressed could potentially cause a 'conservation crisis.' The report challenges previously held beliefs of the impact of illegal bushmeat hunting and trade in Africa with new data from experts.

While the bushmeat trade has long been recognized as a severe threat to the food resources ...

New weapons detail reveals true depth of Cuban Missile Crisis

2012-10-12

The Cuban Missile Crisis took place 50 years ago this October, when US and Soviet leaders pulled back from the very brink of nuclear war. This was the closest the world has come to nuclear war, but exactly how close has been a matter of some speculation. The conflict, itself, has been analyzed and interpreted, but the number and types of nuclear weapons that were operational have not. According to fresh analysis available today in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, published by SAGE, senior experts calculate the nature of weapons capabilities on both sides, and write ...

GMES for Europe

2012-10-12

The potential of GMES for crisis management and environmental monitoring is highlighted in a new publication with users demonstrating the importance of Earth observation data to European regions.

The joint ESA-NEREUS (Network of European Regions Using Space Technologies) publication is a collection of articles that provide insight into how the Global Monitoring for Environment and Security (GMES) programme is being used in new applications and services across Europe.

The articles, prepared by regional end-users, research institutes and industry providers from 17 different ...

Development of 2 tests for rapid diagnosis of resistance to antibiotics

2012-10-12

With their excellent sensitivity and specificity, the use of these extremely efficient tests on a world-wide scale would allow us to adapt antibiotic treatments to the individual's needs and to be more successful in controlling antibiotic resistance, particularly in hospitals. These works were published in September in two international reviews:

Emerging Infectious diseases and The Journal of Clinical Microbiology.

These diagnostic tests will allow rapid identification of certain bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics and hence:

Allow us to better adapt the treatment ...

Scientists identify trigger for explosive volcanic eruptions

2012-10-12

Scientists from the University of Southampton have identified a repeating trigger for the largest explosive volcanic eruptions on Earth.

The Las Cañadas volcanic caldera on Tenerife, in the Canary Islands, has generated at least eight major eruptions during the last 700,000 years. These catastrophic events have resulted in eruption columns of over 25km high and expelled widespread pyroclastic material over 130km. By comparison, even the smallest of these eruptions expelled over 25 times more material than the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull, Iceland.

By analysing ...

The body's own recycling system

2012-10-12

Almost everything that happens inside a cell, including autophagy, is tightly regulated on a biochemical level. Like that, the cell makes sure that processes only take place when they are needed and that they are shut off when the need has expired. "Inside the cell, there exists a network of molecules. Between them, information is constantly being exchanged," says Schmitz, head of the research group "Systems-oriented Immunology and Inflammation Research" at HZI, who also holds a chair at the Otto von Guericke University in Magdeburg. "In a way, it looks like a big city ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

[Press-News.org] Transplantation of embryonic neurons raises hope for treating brain diseasesUCSF experiments challenge prevailing theory for the basis of cell death in the developing brain