(Press-News.org) In the long run, all organisms must adapt to survive as their surroundings do not remain constant for ever. The major difficulty with understanding adaption relates to the length of time required for experiments: evolution is by its very nature a gradual process. Fortunately, however, recent breakthroughs in experimental evolution using model organisms are providing important insights into the process. The nature of the underlying genetic changes has generally remained elusive but recent work at the Institute of Population Genetics of the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna is helping to show us how evolution may operate.

To discover what happens when an organism – in this case the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster – is confronted with new conditions for a prolonged period of time, terWengel and colleagues Martin Kapun and Viola Nolte subjected flies to an unfamiliar temperature regime, in which 12-hour days at 28oC alternated with 12-hour nights at 18oC. Throughout the experiment, the scientists monitored the changes to the flies' DNA by sequencing pools of female flies taken after certain numbers of generations. The complicated study was made possible by developments in sequencing technology that enable the rapid sequencing of entire genomes and by new and sophisticated software algorithms that permit the frequency of gene variants (alleles or polymorphisms) to be directly compared across different populations.

At the start of the experiment, the fly genomes contained sufficient polymorphisms to enable natural selection to act on the population. The researchers were able to confirm that the genetic changes over time were not random but presumably driven by a selective force: the X chromosome proved to be more stable than chromosome III, for example, despite its far smaller population size (each pair of flies carries a total of four copies of chromosome III but only a single X chromosome). They also showed that genetic changes were widespread and rapid: within a mere 15 generations, the frequencies of variants at nearly 5000 positions in the genome had altered significantly more than expected.

Surprisingly, however, not all changes took place at the same rate. The scientists found that while the frequencies of variants of some genes continued to rise throughout the entire course of the study (37 generations), the proportions of alleles of other genes rose rapidly at the start of the experiment but reached a plateau after about 15 generations. The reasons for this levelling out are still unclear but may relate to the fluctuating temperatures employed in the work, which could result in different selective advantages being conferred by several different alleles of a particular gene.

As Schlötterer puts it, "we expected the flies to respond genetically to the changes in their environment. But we did not expect the genetic adaptations to group so neatly into two classes, with so little overlap between them. It will be intriguing to try to find out whether the two categories of gene affect distinct groups of traits."

###

The paper "Adaptation of Drosophila to a novel laboratory environment reveals temporally heterogeneous trajectories of selected alleles" by Pablo Orozco-terWengel, Martin Kapun, Viola Nolte, Robert Kofler, Thomas Flatt and Christian Schlötterer is published in the current issue of "Molecular Ecology" (Mol Ecol. 2012 Oct;21(20):4931-41).

Abstract of the scientific article online (full text for a fee or with a subscription):

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05673.x/abstract

About the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna

The University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna is the only academic and research institution in Austria that focuses on the veterinary sciences. About 1000 employees and 2300 students work on the campus in the north of Vienna, which also houses the animal hospital and various spin-off-companies.

http://www.vetmeduni.ac.at

Scientific contact

Prof. Christian Schlötterer

Institute of Population Genetics

University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna

T +43 1 25077-4300

christian.schloetterer@vetmeduni.ac.at

Distributed by

Klaus Wassermann

Public Relations/Science Communication

University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna

T +43 1 25077-1153

klaus.wassermann@vetmeduni.ac.at END

Directing change: How do they do it?

2012-10-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Young people who go out drinking start earlier and consume more and more alcohol

2012-10-19

Teenagers and university students are unaware of the negative consequences of alcohol consumption or the chances of developing an addiction as a result. In addition, they start at a younger and younger age and drink more and stronger alcohol according to a study headed by the University of Valencia.

Current drinking trends amongst Spanish youth are characterised by what is known as botellón or drinking in the streets. Researchers at Valencia's universities, Miguel Hernández de Elche and Jaume I de Castellón, have conducted a study funded by the Spanish National Drugs ...

A sharper look into the past for archaeology and climate research

2012-10-19

By using a new series of measurements of radiocarbon dates on seasonally laminated sediments from Lake Suigetsu in Japan, a more precise calibration of radiocarbon dating will be possible. In combination with an accurate count of the seasonal layered deposits in the lake, the study resulted in an unprecedented precision of the known 14C method with which it is now possible to date older objects of climate research and archeology more precisely than previously achievable. This is the result published by an international team of geoscientists led by Prof. Christopher Bronk ...

First micro-structure atlas of the human brain completed

2012-10-19

A European team of scientists have built the first atlas of white-matter microstructure in the human brain. The project's final results have the potential to change the face of neuroscience and medicine over the coming decade.

The work relied on groundbreaking MRI technology and was funded by the EU's future and emerging technologies program with a grant of 2.4 million Euros. The participants of the project, called CONNECT, were drawn from leading research centers in countries across Europe including Israel, United Kingdom, Germany, France, Denmark, Switzerland and Italy.

The ...

Sharp rise in children admitted to hospital with throat infections since 1999

2012-10-19

The number of children admitted to hospital in England for acute throat infections increased by 76 per cent between 1999 and 2010, according to new research published today in Archives of Disease in Childhood.

Acute throat infection (ATI), which includes acute tonsillitis and acute pharyngitis, is one of the most common reasons for consulting a GP. The majority of ATIs are self-limiting and can be managed at home or by the GP, but a small proportion may require hospital admission.

This study investigated admission rates for children up to age 17 with ATI alongside ...

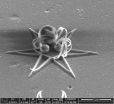

Manufacturing complex 3-D metallic structures at nanoscale made possible

2012-10-19

VIDEO:

The video shows the assembly of a metallic three-dimensional cage, as the nanopatterned film is bent along precisely defined folding lines due to the compressive stress induced by an ion...

Click here for more information.

The fabrication of many objects, machines, and devices around us rely on the controlled deformation of metals by industrial processes such as bending, shearing, and stamping. Is this technology transferrable to nanoscale? Can we build similarly ...

Recession drives down national park visitation, new UGA study finds

2012-10-19

Athens, Ga. – A national recession doesn't just affect Americans' wallets. It also impacts their travel to national parks, a new University of Georgia study has found.

Recent visitation statistics released by the U.S. Department of Interior already noted the significant decrease in national park visitation—dropping nearly 10 million since 1998 to 278 million visitors—but this is the first study to link the drop to a bad economy. The findings could help park managers plan ahead for revenue shortfall and a decrease in visitation, particularly as the economic forecast remains ...

The art of sustainable development

2012-10-19

Montreal, October 19, 2012 – Einstein said that we can't solve problems by using the same kind of thinking used when we created them. Wise words, except few people heed them when it comes to sustainable solutions for our ailing planet. Despite decades of scientific research into everything from air pollution to species extinction, individuals are slow to act because their passions are not being ignited.

For Paul Shrivastava, the Director of the David O'Brien Centre for Sustainable Enterprise at Concordia University's John Molson School of Business (JMSB), combining science ...

Beneficial mold packaged in bioplastic

2012-10-19

This press release is available in Spanish.

Aflatoxins are highly toxic carcinogens produced by several species of Aspergillus fungi. But not all Aspergillus produce aflatoxin. Some, in fact, are considered beneficial. One such strain, dubbed K49, is now being recruited to battle these harmful Aspergillus relatives, preventing them from contaminating host crops like corn with the carcinogen.

In collaboration with University of Bologna (UB) scientists in Italy, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists Hamed Abbas and Bob Zablotowicz (retired) have devised a new ...

Ancient DNA sheds light on Arctic whale mysteries

2012-10-19

NEW YORK (October 18, 2012)—Scientists from the Wildlife Conservation Society, the American Museum of Natural History, City University of New York, and other organizations have published the first range-wide genetic analysis of the bowhead whale using hundreds of samples from both modern populations and archaeological sites used by indigenous Arctic hunters thousands of years ago.

In addition to using DNA samples collected from whales over the past 20 years, the team collected genetic samples from ancient specimens —extracted from old vessels, toys, and housing material ...

Findings could be used to engineer organs

2012-10-19

Biologists have teamed up with mechanical engineers from the University of Texas at Dallas in cell research that provides information that may one day be used to engineer organs.

The research, published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, sheds light into the mechanics of cell, tissue and organ formation. The research revealed basic mechanisms about how a group of bacterial cells can form large three-dimensional structures.

"If you want to create an organism, the geometry of how a group of cells self-organizes is crucial," said Dr. Hongbing ...