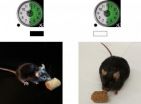

(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA - Fat cells store excess energy and signal these levels to the brain. In a new study this week in Nature Medicine, Georgios Paschos PhD, a research associate in the lab of Garret FitzGerald, MD, FRS director of the Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, shows that deletion of the clock gene Arntl, also known as Bmal1, in fat cells, causes mice to become obese, with a shift in the timing of when this nocturnal species normally eats. These findings shed light on the complex causes of obesity in humans.

The Penn studies are surprising in two respects. "The first is that a relatively modest shift in food consumption into what is normally the rest period for mice can favor energy storage," says Paschos. "Our mice became obese without consuming more calories." Indeed, the Penn researchers could also cause obesity in normal mice by replicating the altered pattern of food consumption observed in mice with a broken clock in their fat cells.

This behavioral change in the mice is somewhat akin to night-eating syndrome in humans, also associated with obesity and originally described by Penn's Albert Stunkard in 1955.

The second surprising observation relates to the molecular clock itself. Traditionally, clocks in peripheral tissues are thought to follow the lead of the "master clock" in the SCN of the brain, a bit like members of an orchestra following a conductor. "While we have long known that peripheral clocks have some capacity for autonomy – the percussionist can bang the drum without instructions from the conductor – here we see that the orchestrated behavior of the percussionist can, itself, influence the conductor," explains FitzGerald.

Daily intake of food is driven by oscillating expression of genes that drive and suppress appetite in the hypothalamus. When the clock was broken in fat cells, the Penn investigators found that this hypothalamic rhythm was disrupted to favor food consumption at the time of inappropriate intake – daytime in mice, nighttime in humans.

When a species' typical daily rhythm is thrown off, changes in metabolism also happen. For example, in people, night shift workers have an increased prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome, and patients with sleep disorders have a higher risk for developing obesity. Also, less sleep means more weight gain in healthy men and women.

Balancing Act

Balancing energy levels in the body requires integrating mul¬tiple signals between the central nervous system and outlying tissues, such as the liver and heart. Fat cells not only store and release energy but also communicate with the brain about the amount of stored energy via the hormone leptin. When leptin is secreted, it causes more energy to be used and less eating via pathways in the hypothalamus.

The Penn team found that only a handful of genes were altered when the clock was broken in fat cells and these governed how unsaturated fatty acids, such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) were released into the blood stream. Interestingly, these are the same fatty acids that are typically associated with fish oils. Sure enough, levels of EPA and DHA were low in both plasma and in the hypothalamus at the time of inappropriate feeding.

"To our amazement, we were able to rescue the entire phenotype - inappropriate fatty acid oscillation and gene expression in the hypothalamus, feeding pattern and obesity - by supplementing EPA and DHA to the knock-out animals," notes Paschos.

The findings point to a role for the fat cell clock molecules in organizing energy regulation and the timing of eating by communicating with the hypothalamus, which ultimately affects stored energy and body weight.

Taken together, these studies emphasize the importance of the molecular clock as an orchestrator of metabolism and reflect a cen¬tral role for fat cells in the integration of food intake and energy expenditure.

"Our findings show that short-term changes have an immediate effect on the rhythms of eating," says FitzGerald. "Over time, these changes lead to an increase in body weight. The conductor is indeed influenced by the percussionist."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (RO1 HL097800) and the Medical Research Council (grant UD99999906).

Co-authors include Salam Ibrahim, Wen-Liang Song, Takeshige Kunieda, Gregory Grant, Teresa M Reyes, Fenfen Wang, and John A Lawson, all from Penn.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $4.3 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine is currently ranked #2 in U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $479.3 million awarded in the 2011 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania -- recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center; and Pennsylvania Hospital — the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Penn Medicine also includes additional patient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2011, Penn Medicine provided $854 million to benefit our community.

It's not just what you eat, but when you eat it

Link between fat cell and brain clock molecules show that missing time piece can cause obesity

2012-11-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Using rust and water to store solar energy as hydrogen

2012-11-12

How can solar energy be stored so that it can be available any time, day or night, when the sun shining or not? EPFL scientists are developing a technology that can transform light energy into a clean fuel that has a neutral carbon footprint: hydrogen. The basic ingredients of the recipe are water and metal oxides, such as iron oxide, better known as rust. Kevin Sivula and his colleagues purposefully limited themselves to inexpensive materials and easily scalable production processes in order to enable an economically viable method for solar hydrogen production. The device, ...

A better brain implant: Slim electrode cozies up to single neurons

2012-11-12

ANN ARBOR—A thin, flexible electrode developed at the University of Michigan is 10 times smaller than the nearest competition and could make long-term measurements of neural activity practical at last.

This kind of technology could eventually be used to send signals to prosthetic limbs, overcoming inflammation larger electrodes cause that damages both the brain and the electrodes.

The main problem that neurons have with electrodes is that they make terrible neighbors. In addition to being enormous compared to the neurons, they are stiff and tend to rub nearby cells ...

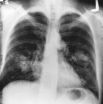

Gene variations linked to lung cancer susceptibility in Asian women

2012-11-12

An international group of scientists has identified three genetic regions that predispose Asian women who have never smoked to lung cancer. The finding provides further evidence that risk of lung cancer among never-smokers, especially Asian women, may be associated with certain unique inherited genetic characteristics that distinguishes it from lung cancer in smokers.

Lung cancer in never-smokers is the seventh leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide, and the majority of lung cancers diagnosed historically among women in Eastern Asia have been in women who never smoked. ...

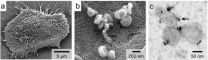

Detection, analysis of 'cell dust' may allow diagnosis, monitoring of brain cancer

2012-11-12

A novel miniature diagnostic platform using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) technology is capable of detecting minuscule cell particles known as microvesicles in a drop of blood. Microvesicles shed by cancer cells are even more numerous than those released by normal cells, so detecting them could prove a simple means for diagnosing cancer. In a study published in Nature Medicine, investigators at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Systems Biology (CSB) demonstrate that microvesicles shed by brain cancer cells can be reliably detected in human blood through ...

Researchers discover 2 genetic flaws behind common form of inherited muscular dystrophy

2012-11-12

SEATTLE – An international research team co-led by a scientist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center has identified two genetic factors behind the third most common form of muscular dystrophy. The findings, published online in Nature Genetics, represent the latest in the team's series of groundbreaking discoveries begun in 2010 regarding the genetic causes of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, or FSHD.

The team, co-led by Stephen Tapscott, M.D., Ph.D., a member of the Hutchinson Center's Human Biology Division, discovered that a rare variant of FSHD, called type ...

Touch-sensitive plastic skin heals itself

2012-11-12

Nobody knows the remarkable properties of human skin like the researchers struggling to emulate it. Not only is our skin sensitive, sending the brain precise information about pressure and temperature, but it also heals efficiently to preserve a protective barrier against the world. Combining these two features in a single synthetic material presented an exciting challenge for Stanford Chemical Engineering Professor Zhenan Bao and her team.

Now, they have succeeded in making the first material that can both sense subtle pressure and heal itself when torn or cut. Their ...

36 in one fell swoop -- researchers observe 'impossible' ionization

2012-11-12

This press release is available in German.

Using the world's most powerful X-ray laser in California, an international research team discovered a surprising behaviour of atoms: with a single X-ray flash, the group led by Daniel Rolles from the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL) in Hamburg (Germany) was able to kick a record number of 36 electrons at once out of a xenon atom. According to theoretical calculations, these are significantly more than should be possible at this energy of the X-ray radiation. The team present their unexpected observations in the ...

'Groundwater inundation' doubles previous predictions of flooding with future sea level rise

2012-11-12

Scientists from the University of Hawaii at Manoa (UHM) published a study today in Nature Climate Change showing that besides marine inundation (flooding), low-lying coastal areas may also be vulnerable to "groundwater inundation," a factor largely unrecognized in earlier predictions on the effects of sea level rise (SLR). Previous research has predicted that by the end of the century, sea level may rise 1 meter. Kolja Rotzoll, Postdoctoral Researcher at the UHM Water Resources Research Center and Charles Fletcher, UHM Associate Dean, found that the flooded area in urban ...

Game changer for arthritis and anti-fibrosis drugs

2012-11-12

(SALT LAKE CITY)—In a discovery that can fundamentally change how drugs for arthritis, and potentially many other diseases, are made, University of Utah medical researchers have identified a way to treat inflammation while potentially minimizing a serious side effect of current medications: the increased risk for infection.

These findings provide a new roadmap for making powerful anti-inflammatory medicines that will be safer not only for arthritis patients but also for millions of others with inflammation-associated diseases, such as diabetes, traumatic brain injury, ...

CSHL-led team discovers new way in which plants control flower production

2012-11-12

Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. – Flowers don't just catch our eyes, they catch those of pollinators like bees as well. They have to, in order to reproduce. Because plants need to maximize the opportunity for pollinators to gain access to their seeds, variations in the timing of flowering can have profound effects on flower, fruit, and seed production, and consequently agricultural yields.

We know that the major driving forces of flowering are external factors such as light and temperature. However, new research from CSHL Assistant Professor Zach Lippman, Ph.D. and his collaborators, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Cal Poly’s fifth Climate Solutions Now conference to take place Feb. 23-27

Mask-wearing during COVID-19 linked to reduced air pollution–triggered heart attack risk in Japan

Achieving cross-coupling reactions of fatty amide reduction radicals via iridium-photorelay catalysis and other strategies

Shorter may be sweeter: Study finds 15-second health ads can curb junk food cravings

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

Calibr-Skaggs and Kainomyx launch collaboration to pioneer novel malaria treatments

JAX-NYSCF Collaborative and GSK announce collaboration to advance translational models for neurodegenerative disease research

[Press-News.org] It's not just what you eat, but when you eat itLink between fat cell and brain clock molecules show that missing time piece can cause obesity