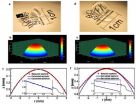

(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON, Nov. 13—Drawing heavily upon nature for inspiration, a team of researchers has created a new artificial lens that is nearly identical to the natural lens of the human eye. This innovative lens, which is made up of thousands of nanoscale polymer layers, may one day provide a more natural performance in implantable lenses to replace damaged or diseased human eye lenses, as well as consumer vision products; it also may lead to superior ground and aerial surveillance technology.

This work, which the Case Western Reserve University, Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, and PolymerPlus team describes in the Optical Society's (OSA) open-access journal Optics Express, also provides a new material approach for fabricating synthetic polymer lenses.

The fundamental technology behind this new lens is called "GRIN" or gradient refractive index optics. In GRIN, light gets bent, or refracted, by varying degrees as it passes through a lens or other transparent material. This is in contrast to traditional lenses, like those found in optical telescopes and microscopes, which use their surface shape or single index of refraction to bend light one way or another.

"The human eye is a GRIN lens," said Michael Ponting, polymer scientist and president of PolymerPlus, an Ohio-based Case Western Reserve spinoff launched in 2010. "As light passes from the front of the human eye lens to the back, light rays are refracted by varying degrees. It's a very efficient means of controlling the pathway of light without relying on complicated optics, and one that we attempted to mimic."

The first steps along this line were taken by other researchers[1, 2] and resulted in a lens design for an aging human eye, but the technology did not exist to replicate the gradual evolution of refraction.

The research team's new approach was to follow nature's example and build a lens by stacking thousands and thousands of nanoscale layers, each with slightly different optical properties, to produce a lens that gradually varies its refractive index, which adjusts the refractive properties of the polymer.

"Applying naturally occurring material architectures, similar to those found in the layers of butterfly wing scales, human tendons, and even in the human eye, to multilayered plastic systems has enabled discoveries and products with enhanced mechanical strength, novel reflective properties, and optics with enhanced power," explains Ponting.

To make the layers for the lens, the team used a multilayer-film coextrusion technique (a common method used to produce multilayer structures). This fabrication technique allows each layer to have a unique refractive index that can then be laminated and shaped into GRIN optics.

It also provides the freedom to stack any combination of the unique refractive index nanolayered films. This is extremely significant and enabled the fabrication of GRIN optics previously unattainable through other fabrication techniques.

GRIN optics may find use in miniaturized medical imaging devices or implantable lenses. "A copy of the human eye lens is a first step toward demonstrating the capabilities, eventual biocompatible and possibly deformable material systems necessary to improve the current technology used in optical implants," Ponting says.

Current generation intraocular replacement lenses, like those used to treat cataracts, use their shape to focus light to a precise prescription, much like contacts or eye glasses. Unfortunately, intraocular lenses never achieve the same performance of natural lenses because they lack the ability to incrementally change the refraction of light. This single-refraction replacement lens can create aberrations and other unwanted optical effects.

And the added power of GRIN also enables optical systems with fewer components, which is important for consumer vision products and ground- and aerial-based military surveillance products.

This technology has already moved from the research labs of Case Western Reserve to PolymerPlus for commercialization. "Prototype and small batch fabrication facilities exist and we're working toward selecting early adoption applications for nanolayered GRIN technology in commercial devices," notes Ponting.

INFORMATION:

Paper: "A Bio-Inspired Polymeric Gradient Refractive Index Human Eye Lens," Optics Express, Vol. 20, Issue 24, pp. 26746-26754 (2012) (http://www.opticsinfobase.org/oe/abstract.cfm?uri=oe-16-15-11540)

EDITOR'S NOTE: Images of the GRIN lens are available to members of the media upon request. Contact Angela Stark, astark@osa.org.

About Optics Express

Optics Express reports on new developments in all fields of optical science and technology every two weeks. The journal provides rapid publication of original, peer-reviewed papers. It is published by the Optical Society and edited by C. Martijn de Sterke of the University of Sydney. Optics Express is an open-access journal and is available at no cost to readers online at http://www.OpticsInfoBase.org/OE.

About OSA

Uniting more than 180,000 professionals from 175 countries, the Optical Society (OSA) brings together the global optics community through its programs and initiatives. Since 1916 OSA has worked to advance the common interests of the field, providing educational resources to the scientists, engineers and business leaders who work in the field by promoting the science of light and the advanced technologies made possible by optics and photonics. OSA publications, events, technical groups and programs foster optics knowledge and scientific collaboration among all those with an interest in optics and photonics. For more information, visit www.osa.org.

References:

1. J. A. Díaz, C. Pizarro, and J. Arasa, "Single dispersive gradient-index profile for the aging human eye lens," J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 25, 250-261 (2008).

2. C.E. Campbell, "Nested shell optical model of the lens of the human eye," J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 27, 2432-2441 (2010).

Human eye gives researchers visionary design for new, more natural lens technology

2012-11-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Doubling down against diabetes

2012-11-13

This press release is available in German.

A collaboration between scientists in Munich, Germany and Bloomington, USA may have overcome one of the major challenges drug makers have struggled with for years: Delivering powerful nuclear hormones to specific tissues, while keeping them away from others.

The teams led by physician Matthias Tschöp (Helmholtz Zentrum München, and Technische Universität München) and chemist Richard DiMarchi (Indiana University) used natural gut peptides targeting cell membrane receptors and engineered them to carry small steroids known to ...

New study examines how health affects happiness

2012-11-13

Fairfax, Va., (November 13, 2012) — A new study published in the Journal of Happiness Studies found that the degree to which a disease disrupts daily functioning is associated with reduced happiness.

Lead author Erik Angner, associate professor of philosophy, economics and public policy at George Mason University, worked with an interdisciplinary team of researchers from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the University of Chicago and the University of Massachusetts Medical School. The full study is available at http://www.springerlink.com/content/k5231631755g86g2/?MUD=MP.

Previous ...

Advocacy for planned home birth not in patients' best interest

2012-11-13

Philadelphia, PA, November 13, 2012 – Advocates of planned home birth have emphasized its benefits for patient safety, patient satisfaction, cost effectiveness, and respect for women's rights. A clinical opinion paper published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology critically evaluates each of these claims in its effort to identify professionally appropriate responses of obstetricians and other concerned physicians to planned home birth.

Throughout the United States and Europe, planned home birth has seen increased activity in recent years. Professional ...

Study sheds light on genetic 'clock' in embryonic cells

2012-11-13

As they develop, vertebrate embryos form vertebrae in a sequential, time-controlled way. Scientists have determined previously that this process of body segmentation is controlled by a kind of "clock," regulated by the oscillating activity of certain genes within embryonic cells. But questions remain about how precisely this timing system works.

A new international cross-disciplinary collaboration between physicists and molecular genetics researchers advances scientists' understanding of this crucial biological timing system. The study, co-authored by McGill University ...

Underemployment persists since recession, with youngest workers hardest hit

2012-11-13

DURHAM, N.H. – Underemployment has remained persistently high in the aftermath of the Great Recession with workers younger than 30 especially feeling the pinch, according to new research from the Carsey Institute at the University of New Hampshire.

"While on the decline, these rates have yet to return to their prerecession levels. Moreover, as the recession and other economic forces keeps older workers in the economy, openings for full-time jobs for younger workers might remain limited in the short-term," said Justin Young, a doctoral student in sociology at UNH and a ...

Edison Pharmaceuticals announces initiation of EPI-743 Phase 2B Leigh Syndrome Clinical Trial

2012-11-13

Mountain View, California; November 13, 2012. Edison Pharmaceuticals today announced the initiation of a phase 2B study entitled, "A Phase 2B Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Clinical Trial of EPI-743 in Children with Leigh Syndrome." Four clinical trial sites have been selected in the United States: Lucile Packard Children's Hospital, Stanford University Medical Center – Palo Alto, California; Akron Children's Hospital – Akron, Ohio; Seattle Children's Hospital – Seattle, Washington; and Texas Children's Hospital, Baylor University – Houston, Texas.

The ...

A sip of resveratrol and a full p53: Ingredients for a successful cell death

2012-11-13

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil- Resveratrol is a naturally occurring dietary compound found in grapes, berries, and peanuts. This polyphenol protects plants against pathogens such as bacteria and fungi by inducing cell death in invading organisms. The compound was discovered in red wine in 1939 but by large did not attract the attention of the scientific community. More recently, pre-clinical studies have revealed the many beneficial properties of resveratrol. These include antidiabetic, cardioprotective, and chemopreventive effects. The latter has been associated to resveratrol ...

Should hyperbaric oxygen therapy be used to treat combat-related mild traumatic brain injury?

2012-11-13

New Rochelle, NY, November 13, 2012—The average incidence of traumatic brain injury (TBI) among service members deployed in Middle East conflict zones has increased 117% in recent years, mainly due to proximity to explosive blasts. Therapeutic exposure to a high oxygen environment was hoped to minimize the concussion symptoms resulting from mild TBI, but hyperbaric oxygen (HBO2) treatment may not offer significant advantages, according to an article in Journal of Neurotrauma, a peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. The article is available free ...

Trying to save money? Ask for crisp new bills at the bank

2012-11-13

Consumers will spend more to get rid of worn bills because they evoke feelings of disgust but are more likely to hold on to crisp new currency, according to a new study in the Journal of Consumer Research.

"The physical appearance of money can alter spending behavior. Consumers tend to infer that worn bills are used and contaminated, whereas crisp bills give them a sense of pride in owning bills that can be spent around others," write authors Fabrizio Di Muro (University of Winnipeg) and Theodore J. Noseworthy (University of Guelph).

Does the physical appearance of ...

CU-NOAA study shows summer climate change, mostly warming

2012-11-13

Analysis of 90 years of observational data has revealed that summer climates in regions across the globe are changing -- mostly, but not always, warming --according to a new study led by a scientist from the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences headquartered at the University of Colorado Boulder.

"It is the first time that we show on a local scale that there are significant changes in summer temperatures," said lead author CIRES scientist Irina Mahlstein. "This result shows us that we are experiencing a new summer climate regime in some regions."

The ...