(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio – A new way to visualize single-cell activity in living zebrafish embryos has allowed scientists to clarify how cells line up in the right place at the right time to receive signals about the next phase of their life.

Scientists developed the imaging tool in single living cells by fusing a protein defining the cells' cyclical behavior to a yellow fluorescent protein that allows for visualization. Zebrafish embryos are already transparent, but with this closer microscopic look at the earliest stages of life, the researchers have answered two long-standing questions about how cells cooperate to form embryonic segments that later become muscle and vertebrae.

Though these scientists are looking at the molecular "clock" that defines the timing of embryonic segmentation, the findings increase understanding of cyclical behaviors in all types of cells at many developmental stages – including problem cells that cause cancer and other diseases. Understanding how to manipulate these clocks or the signals that control them could lead to new ways to treat certain human conditions, researchers say.

Embryonic cells go through oscillating cycles of high and low signal reception in the process of making segmented tissue, and gene activation by the groups of cells must remain synchronized for the segments to form properly. One of a handful of powerful messaging systems in all vertebrates is called the Notch signaling pathway, and its precise role in this oscillation and synchronization has been a mystery until now.

In this study, the researchers confirmed that the cells must receive the Notch signal to maintain synchronization with nearby cells and form segments that will become tissue, but the cells can activate their genes in oscillating patterns with or without the signal.

"For the first time, this nails it," said Sharon Amacher, professor of molecular genetics at Ohio State University and lead author of the study. "This provides the data that cells with disabled Notch signaling can oscillate just fine, but what they can't do is synchronize with their neighbors."

The imaging also allowed Amacher and colleagues to determine that cell division, called mitosis, is not a random event as was once believed. Instead, division tends to occur when neighboring cells are at a low point of gene activation for signal reception – suggesting mitosis is not as "noisy," or potentially disruptive, as it was previously assumed.

The study is published in the November issue of the journal Developmental Cell.

Amacher's work focuses on the creation of these tissue segments, called somites, in the mesoderm of zebrafish embryos – this region gives rise to the ribs, vertebrae and muscle in all vertebrates, including humans.

"This early process of segmentation is really important for patterning a lot of subsequent developmental events – the patterning of the nervous system and the vasculature, much of that depends on this clock ensuring that early development happens properly," Amacher said.

Unlike the well-known 24-hour Circadian clock, however, the activities of cells at the earliest stages of development can occur within a matter of minutes – which makes their clocks very challenging to study.

This research was aided by collaboration among biologists and physicists, including development of a powerful MATLAB-based computational analysis by co-author Paul François, assistant professor of physics at McGill University. François helped to semi-automate cell tracking, as well as to convert raw data about each cell's phase into maps enabling more specific visualizations. He worked with Emilie Delaune, a postdoctoral fellow who constructed the imaging tool and had previously tracked cells by hand, and graduate student Nathan Shih. Amacher, Delaune and Shih conducted the research while at the University of California, Berkeley. Amacher joined the Ohio State faculty in July.

Experts in tissue segmentation liken the oscillating cycle of gene activation and de-activation that cells go through before they form somites to the wave that fans perform in a stadium. According to the segmentation clock, genes are turned on, proteins are made, proteins then inhibit gene activation, and so on, and the pattern repeats until all necessary somites are formed. Neighbor cells must be in sync with each other just as sports fans in the same section must stand and sit at the same time to effectively form a wave.

Zebrafish somites form every 30 minutes, meaning that during any one cycle of the wave, a cell is engaged in making protein for only about five minutes. To generate the imaging tool, researchers linked a yellow fluorescent protein to a cyclic protein known to have a short lifespan. The resulting short-lived fluorescent fusion protein allowed Amacher and colleagues to look at single cells along with their neighbors to observe how they stayed synchronized as they did the wave.

Researchers in this field had previously thought that the Notch signaling pathway may be needed to start the clock in these cyclic genes, though conflicting data had shown that the clock could run without the signal.

Amacher's imaging showed that, indeed, Notch was required only to maintain synchronization, but not to start the oscillating clock. She and colleagues tested this idea by combining the imaging tool with three mutant cell types with disabled Notch signals. Cells in all three mutants could oscillate, but not in a synchronized fashion, explaining how they failed to form segments in the way that cells receiving the Notch signal could.

Defects in Notch signaling are associated with human congenital developmental disorders characterized by malformed ribs and vertebrae, suggesting this work offers insight into potential therapies to prevent these defects.

The researchers next sought to determine whether cell division interrupted the synchrony needed for creation of the segments. Mitosis, occurring among 10 to 15 percent of embryonic cells at any one time, is considered a source of biological "noise" because when cells divide, they stop activating genes. If division were happening randomly, as previously thought, instead of in a pattern, the very cell division needed for organism growth could also disrupt clock synchrony, creating problems that segmenting organisms would have to overcome.

The study showed, however, that most cells divided when their neighbors were at a low point of gene activation – at the bottom of a wave – suggesting that cell division doesn't occur at random. The study team noted that the two daughter cells created from a fresh division are more tightly synchronized with each other than are any other cell neighbors in the area.

Under normal conditions, these two daughters resynchronize with their neighbors in short order. In embryos lacking Notch signaling, newly divided daughters appeared as a pair of tightly synchronous cells in a largely asynchronous sea, showing that oscillation could resume without the signaling pathway. Without Notch, the daughter cells gradually drifted out of synchrony, becoming like their asynchronous neighbors.

Amacher said these findings could be incorporated into models of developmental cell behavior to further advance cell biology research.

"Most of our tissues and organs are not made up of the same types of cells. They have different jobs. So you don't want them to respond identically to every signal; you want them to have different responses," she said. "We need to understand systems like this that help cells not only interpret the signals in their environment, but do the right thing when they get that signal."

###

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Association Française contre les Myopathies, a Marie-Curie Outgoing International Fellowship, a Pew Scholar Award, the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant program and Regroupement Québécois pour les matériaux de pointe.

Contact: Sharon Amacher, (614) 292-8084; Amacher.6@osu.edu

Written by Emily Caldwell, (614) 292-8310; Caldwell.151@osu.edu

How do cells tell time? Scientists develop single-cell imaging to watch the cell clock

2012-11-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Powering lasers through heat

2012-11-13

This press release is available in German.

Since its invention 50 years ago, laser light has conquered our daily life. Lasers of varying wave lengths and power are used in many parts of our life, from consumer electronics to telecommunication and medicine. However, not all wave lengths have been equally well researched. For the far infrared and terahertz regime quantum cascade lasers are the most important source of coherent radiation. Light amplification in such a cascade laser is achieved through a repeated pattern of specifically designed semi-conductor layers of ...

Sperm length variation is not a good sign for fertility

2012-11-13

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Perhaps variety is the very spice of life, but as a matter of producing human life, it could be the bane of existence. That's the indication of a new study in the journal Human Reproduction that found men with wider variation in sperm length, particularly in the flagellum, had lower concentrations of sperm that could swim well. Those with more consistently made sperm seemed to have more capable ones.

"Our study reveals that men who produce higher concentrations of competent swimming sperm also demonstrate less variation in the size ...

Computer memory could increase fivefold from advances in self-assembling polymers

2012-11-13

AUSTIN, Texas — The storage capacity of hard disk drives could increase by a factor of five thanks to processes developed by chemists and engineers at The University of Texas at Austin.

The researchers' technique, which relies on self-organizing substances known as block copolymers, was described this week in an article in Science. It's also being given a real-world test run in collaboration with HGST, one of the world's leading innovators in disk drives.

"In the last few decades there's been a steady, exponential increase in the amount of information that can be stored ...

Human eye gives researchers visionary design for new, more natural lens technology

2012-11-13

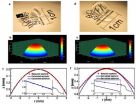

WASHINGTON, Nov. 13—Drawing heavily upon nature for inspiration, a team of researchers has created a new artificial lens that is nearly identical to the natural lens of the human eye. This innovative lens, which is made up of thousands of nanoscale polymer layers, may one day provide a more natural performance in implantable lenses to replace damaged or diseased human eye lenses, as well as consumer vision products; it also may lead to superior ground and aerial surveillance technology.

This work, which the Case Western Reserve University, Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, ...

Doubling down against diabetes

2012-11-13

This press release is available in German.

A collaboration between scientists in Munich, Germany and Bloomington, USA may have overcome one of the major challenges drug makers have struggled with for years: Delivering powerful nuclear hormones to specific tissues, while keeping them away from others.

The teams led by physician Matthias Tschöp (Helmholtz Zentrum München, and Technische Universität München) and chemist Richard DiMarchi (Indiana University) used natural gut peptides targeting cell membrane receptors and engineered them to carry small steroids known to ...

New study examines how health affects happiness

2012-11-13

Fairfax, Va., (November 13, 2012) — A new study published in the Journal of Happiness Studies found that the degree to which a disease disrupts daily functioning is associated with reduced happiness.

Lead author Erik Angner, associate professor of philosophy, economics and public policy at George Mason University, worked with an interdisciplinary team of researchers from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the University of Chicago and the University of Massachusetts Medical School. The full study is available at http://www.springerlink.com/content/k5231631755g86g2/?MUD=MP.

Previous ...

Advocacy for planned home birth not in patients' best interest

2012-11-13

Philadelphia, PA, November 13, 2012 – Advocates of planned home birth have emphasized its benefits for patient safety, patient satisfaction, cost effectiveness, and respect for women's rights. A clinical opinion paper published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology critically evaluates each of these claims in its effort to identify professionally appropriate responses of obstetricians and other concerned physicians to planned home birth.

Throughout the United States and Europe, planned home birth has seen increased activity in recent years. Professional ...

Study sheds light on genetic 'clock' in embryonic cells

2012-11-13

As they develop, vertebrate embryos form vertebrae in a sequential, time-controlled way. Scientists have determined previously that this process of body segmentation is controlled by a kind of "clock," regulated by the oscillating activity of certain genes within embryonic cells. But questions remain about how precisely this timing system works.

A new international cross-disciplinary collaboration between physicists and molecular genetics researchers advances scientists' understanding of this crucial biological timing system. The study, co-authored by McGill University ...

Underemployment persists since recession, with youngest workers hardest hit

2012-11-13

DURHAM, N.H. – Underemployment has remained persistently high in the aftermath of the Great Recession with workers younger than 30 especially feeling the pinch, according to new research from the Carsey Institute at the University of New Hampshire.

"While on the decline, these rates have yet to return to their prerecession levels. Moreover, as the recession and other economic forces keeps older workers in the economy, openings for full-time jobs for younger workers might remain limited in the short-term," said Justin Young, a doctoral student in sociology at UNH and a ...

Edison Pharmaceuticals announces initiation of EPI-743 Phase 2B Leigh Syndrome Clinical Trial

2012-11-13

Mountain View, California; November 13, 2012. Edison Pharmaceuticals today announced the initiation of a phase 2B study entitled, "A Phase 2B Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Clinical Trial of EPI-743 in Children with Leigh Syndrome." Four clinical trial sites have been selected in the United States: Lucile Packard Children's Hospital, Stanford University Medical Center – Palo Alto, California; Akron Children's Hospital – Akron, Ohio; Seattle Children's Hospital – Seattle, Washington; and Texas Children's Hospital, Baylor University – Houston, Texas.

The ...