(Press-News.org) This press release is available in German.

When infected with influenza, the body becomes an easy target for bacteria. The flu virus alters the host's immune system and compromises its capacity to effectively fight off bacterial infections. Now, a team of immunologists at the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI) and cooperation partners has discovered that an immune system molecule called TLR7 is partly to blame. The molecule recognizes the viral genome – and then signals scavenger cells of the immune system to ingest fewer bacteria. The researchers published their findings in the Journal of Innate Immunity.

The flu is not just a seasonal illness during the winter months. In the past, there have been several flu pandemics that have claimed the lives of millions. By now, we know that during the course of the disease, many people not only get sick from the flu itself but also from bacterial pathogens like the much-feared pneumococci, the bacteria causing pneumonia. In many cases, such "superinfections" can cause the disease to take a turn for the worse. In fact, during the Spanish Flu of 1918 to 1920, they were responsible for the majority of deaths. Why an infection with the flu virus increases the risk for superinfections is still poorly understood. Now, a group of scientists from HZI, the University Hospital of the Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg, the Essen University Hospital, the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, as well as further research institutions have discovered one more detail on how the virus manipulates the immune system.

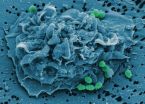

They focused on TLR7, a molecule that is found in different cells of the body. TLR7 is capable of recognizing viral genetic material. As it turns out, TLR7 has an unwanted side effect, too: During a flu infection, it appears to undermine the body's innate ability to fight off bacteria, thereby increasing the chance of a superinfection. The researchers made their discovery when they examined how superinfected mice were dealing with the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae, the pneumonia pathogen. The scientists colored the bacteria and measured how many of them were taken up by scavenger cells of the immune system called macrophages. The macrophages of TLR7-deficient mice had a bigger appetite and eliminated larger numbers of bacteria when infected with the flu than those of mice with the intact viral sensor. "Without TLR7, it takes longer before influenza-infected mice reach the critical point where they are no longer able to cope with the bacterial infection," explains Prof. Dunja Bruder, head of HZI's "Immune Regulation Group" and professor of infection immunology at the University Hospital Magdeburg.

The scientists also have an idea about how TLR7 may be curtailing the scavenger cells' appetite: Whenever the immune system recognizes a virus, it gets other immune cells to produce a signaling substance called IFN gamma. It is already known that this substance inhibits macrophages in the lungs, causing them to eliminate fewer bacteria. As part of their study, the researchers discovered another indication of this special relationship: In TLR7-deficient animals they found smaller quantities of the IFN gamma messenger substance. The consequence might be that macrophages have a bigger appetite and that therefore bacterial entry into the bloodstream is delayed.

"Our results confirm that in the long run the flu virus suppresses the body's ability to defend itself against bacteria. Presumably, this is an unwanted side effect of the viral infection," speculates Dr. Stegemann-Koniszewski, the study's first author.

"Unfortunately, it is rather difficult to intervene therapeutically. At first glance, it seems obvious to inhibit TLR7 during influenza so that the macrophages are actually able to get rid of the bacteria. However, this could have unforeseen repercussions as TLR7 and IFN gamma are both part of a tightly regulated immunological network," explains Prof. Matthias Gunzer, former research group leader at the HZI and currently a professor at Essen University Hospital.

Even if a lack of TLR7 cannot by itself ward off a bacterial superinfection, the researchers' findings could still lead to highly promising potential clinical applications. "Missing TLR7 delays the spread of bacteria via the bloodstream," says Bruder. "Even if we are only talking about a relatively brief window of time, this might be our critical opportunity for keeping a seriously ill patient alive. The more time doctors have to choose the right antibiotic for their patient, the better the chances of a successful treatment."

INFORMATION:

Original Publication

Sabine Stegemann-Koniszewski, Marcus Gereke, Sofia Orrskog, Stefan Lienenklaus, Bastian Pasche, Sophie R. Bader, Achim D. Gruber, Shizuo Akira, Siegfried Weiss, Birgitta Henriques-Normark, Dunja Bruder*, Matthias Gunzer* (* These authors contributed equally to the study.)

TLR7 contributes to the rapid progression but not to the overall fatal outcome of secondary pneumococcal disease following influenza A virus infection

Journal of Innate Immunity, 2012

DOI: 10.1159/000345112

The research group "Immune Regulation" at the HZI explores the immune system under extreme situations. These can be parallel infections with different pathogens or the erroneous attack of parts of the own body by the immune system.

The Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI):

The Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research contributes to the achievement of the goals of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres and to the successful implementation of the research strategy of the German Federal Government. The goal is to meet the challenges in infection research and make a contribution to public health with new strategies for the prevention and therapy of infectious diseases.

www.helmholtz-hzi.de

Appetite suppressant for scavenger cells

Influenza curbs part of the immune system and abets bacterial infections

2012-11-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

This is your brain on freestyle rap

2012-11-15

Researchers in the voice, speech, and language branch of the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have used functional magnetic resonance imaging to study the brain activity of rappers when they are "freestyling" – spontaneously improvising lyrics in real time. The findings, published online in the November 15 issue of the journal Scientific Reports, reveal that this form of vocal improvisation is associated with a unique functional reallocation of brain activity in the prefrontal cortex and ...

About one million species inhabit the ocean

2012-11-15

Every taxonomist has calculated the number of existing species within their specialty and estimated the number that remain to be discovered, both through statistical models as based on the experience of each expert. According to Enrique Macpherson, researcher at the Center for Advanced Studies of Blanes (CEAB-CSIC, Spain), who has participated in the study: "Bringing together the leading taxonomists around the world to pool their information has been the great merit of this research".

The statistical prediction is based on the rate of description for new species in recent ...

Penn study decodes molecular mechanisms underlying stem cell reprogramming

2012-11-15

PHILADELPHIA – Fifty years ago, British researcher John Gurdon demonstrated that genetic material from non-reproductive, or somatic, cells could be reprogrammed into an embryonic state when transferred into an egg. In 2006, Kyoto University researcher Shinya Yamanaka expanded on those findings by expressing four proteins in mouse somatic cells to rewind their genetic clocks, converting them into embryonic-like stem cells called induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPS cells.

In early October, Gurdon and Yamanaka were awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine ...

Early 50s may be key time to reach baby boomers with health messages

2012-11-15

COLUMBUS, Ohio -- For baby boomers, the peak interest in health issues comes at about age 51, with a second peak coming near age 65, according to a new study.

The results may help doctors and other professionals target this generation with health messages at a time when they are most receptive to hearing them, the researchers said.

The study, based on a survey of Americans age 45 to 65, showed that people in their late 40s had the lowest levels of interest in health issues. Interest rose quickly, however, and peaked in the early 50s, then dropped slightly and plateaued ...

Feinstein Institute researchers discover plant derivative

2012-11-15

MANHASSET, NY – Researchers at The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research have discovered that tanshinones, which come from the plant Danshen and are highly valued in Chinese traditional medicine, protect against the life-threatening condition sepsis. The findings are published in the December issue of Biochemical Pharmacology.

Inflammation is necessary for maintaining good health – without inflammation, wounds and infections would never heal. However, persistent and constant inflammation can damage tissue and organs, and lead to diseases such as sepsis. Sepsis affects ...

Researchers tap into CO2 storage potential of mine waste

2012-11-15

VANCOUVER, CANADA, NOVEMBER 15, 2012 -- It's time to economically value the greenhouse gas-trapping potential of mine waste and start making money from it, says mining engineer and geologist Michael Hitch of the University of British Columbia (UBC).

Hitch studies the value of mine waste rock for its CO2-sequestration potential, or "SP." He says mining companies across Canada will, in future, be able to offset CO2 emissions with so-named "SP rock," and within 25 years could even be selling emissions credits.

Digging, trucking and processing make mining an energy-intensive ...

Eating more fish could reduce postpartum depression

2012-11-15

Low levels of omega-3 may be behind postpartum depression, according to a review lead by Gabriel Shapiro of the University of Montreal and the Research Centre at the Sainte-Justine Mother and Child Hospital. Women are at the highest risk of depression during their childbearing years, and the birth of a child may trigger a depressive episode in vulnerable women. Postpartum depression is associated with diminished maternal health as well as developmental and health problems for her child. "The literature shows that there could be a link between pregnancy, omega-3 and the ...

Family commitment blended with strong religion dampens civic participation, Baylor researcher finds

2012-11-15

Blending religion with familism — a strong commitment to lifelong marriage and childbearing — dampens secular civic participation, according to research by a Baylor University sociologist.

"Strong family and strong religion. What happens when they meet? Is that good for the larger society? It is not always as it seems," said Young-Il Kim, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Fellow in Baylor's Institute for Studies of Religion.

His study — "Bonding alone: Familism, religion and secular civic participation" — is published online in Social Science Research. The findings are based on analysis ...

New study finds milk-drinking kids reap physical benefits later in life

2012-11-15

Starting a milk drinking habit as a child can lead to lifelong benefits, even improving physical ability and balance in older age, according to new research. A new study published in Age & Aging found an increase of about one glass of milk a day as a child was linked to a 5% faster walking time and 25% lesser chance of poor balance in older age. The researchers suggest a "public health benefit of childhood milk intake on physical function in old age" – a finding that has huge potential for adults over 65, a population expected reach more than 70 million by the year 2030, ...

How 'black swans' and 'perfect storms' become lame excuses for bad risk management

2012-11-15

The terms "black swan" and "perfect storm" have become part of public vocabulary for describing disasters ranging from the 2008 meltdown in the financial sector to the terrorist attacks of September 11. But according to Elisabeth Paté-Cornell, a Stanford professor of management science and engineering, people in government and industry are using these terms too liberally in the aftermath of a disaster as an excuse for poor planning.

Her research, published in the November issue of the journal Risk Analysis, suggests that other fields could borrow risk analysis strategies ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

Muscular strength and mortality in women ages 63 to 99

[Press-News.org] Appetite suppressant for scavenger cellsInfluenza curbs part of the immune system and abets bacterial infections