(Press-News.org) The structure and processes of United Nations climate negotiations are "antiquated", unfair and obstruct attempts to reach agreements, according to research published today.

The findings come ahead of the 18th UN Climate Change Summit, which starts in Doha on November 26.

The study, led by Dr Heike Schroeder from the University of East Anglia (UEA) and the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, argues that the consensus-based decision making used by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) stifles progress and contributes to negotiating deadlocks, which ultimately hurts poor countries more than rich countries.

It shows that delegations from some countries taking part have increased in size over the years, while others have decreased, limiting poor countries' negotiating power and making their participation less effective.

Writing in the journal Nature Climate Change, Dr Schroeder, Dr Maxwell Boykoff of the University of Colorado and Laura Spiers of Pricewaterhouse Coopers, argue that changes are long overdue if demands for climate mitigation and adaptation agreements are to be met.

They recommend that countries consider capping delegation numbers at a level that allows broad representation across government departments and sectors of society, while maintaining a manageable overall size.

Dr Schroeder, of UEA's School of International Development, will be attending COP18. She said: "The UN must recognize that these antiquated structures serve to constrain rather than compel co-operation on international climate policy. The time is long overdue for changes to institutions and structures that do not support decision-making and agreements.

"Poor countries cannot afford to send large delegations and their level of expertise usually remains significantly below that of wealthier countries. This limits poor countries' negotiating power and makes their participation in each session less effective."

The researchers found that attendance has changed in terms of the number and diversity of representatives. The number of delegates went from 757 representing 170 countries at the first COP in 1995 to 10,591 individuals from 194 countries attending COP15 in 2009 – a 1400 per cent increase. At COP15 there were also 13,500 delegates from 937 non-government Observer organisations.

Small developing countries have down-sized their delegations while G-7 and +5 countries (Brazil, China, India, Mexico, and South Africa) have increased theirs. The exception is the United States, which after withdrawing from the Kyoto Protocol started to send fewer delegates to COPs.

The study, Equity and state representations in climate negotiations, also looked at the make-up of the delegations and found an increase in participation by environmental, campaigning, academic and other non-Governmental organisations.

"Our work shows an increasing trend in the size of delegations on one side and a change in the intensity, profile and politicization of the negotiations on the other," explained Dr Schroeder. "These variations suggest the climate change issue and its associated interests are framed quite differently across countries. NSAs are well represented on national delegations but clearly the government decides who is included and who is not, and what the official negotiating position of the country and its level of negotiating flexibility are."

Some countries send large representations from business associations (Brazil), local government (Canada) orscience and academia (Russia). For small developing countries such as Bhutan and Gabon the majority of government representatives come from environment, forestry and agriculture. The UK has moved from mainly environment, forestry and agriculture to energy and natural resources. The US has shifted from these more conventional areas to an overwhelming representation from the US Congress at COP15.

### END

Call to modernize antiquated climate negotiations

2012-11-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

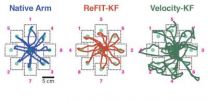

A better thought-controlled computer cursor

2012-11-19

When a paralyzed person imagines moving a limb, cells in the part of the brain that controls movement still activate as if trying to make the immobile limb work again. Despite neurological injury or disease that has severed the pathway between brain and muscle, the region where the signals originate remains intact and functional.

In recent years, neuroscientists and neuroengineers working in prosthetics have begun to develop brain-implantable sensors that can measure signals from individual neurons, and after passing those signals through a mathematical decode algorithm, ...

Fabrication on patterned silicon carbide produces bandgap to advance graphene electronics

2012-11-19

By fabricating graphene structures atop nanometer-scale "steps" etched into silicon carbide, researchers have for the first time created a substantial electronic bandgap in the material suitable for room-temperature electronics. Use of nanoscale topography to control the properties of graphene could facilitate fabrication of transistors and other devices, potentially opening the door for developing all-carbon integrated circuits.

Researchers have measured a bandgap of approximately 0.5 electron-volts in 1.4-nanometer bent sections of graphene nanoribbons. The development ...

Breakthrough nanoparticle halts multiple sclerosis

2012-11-19

New nanoparticle tricks and resets immune system in mice with MS

First MS approach that doesn't suppress immune system

Clinical trial for MS patients shows why nanoparticle is best option

Nanoparticle now being tested in Type 1 diabetes and asthma

CHICAGO --- In a breakthrough for nanotechnology and multiple sclerosis, a biodegradable nanoparticle turns out to be the perfect vehicle to stealthily deliver an antigen that tricks the immune system into stopping its attack on myelin and halt a model of relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) in mice, according ...

Research breakthrough selectively represses the immune system

2012-11-19

Reporters, please see "For news media only" box at the end of the release for embargoed sound bites of researchers.

In a mouse model of multiple sclerosis (MS), researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health have developed innovative technology to selectively inhibit the part of the immune system responsible for attacking myelin—the insulating material that encases nerve fibers and facilitates electrical communication between brain cells.

Autoimmune disorders occur when T-cells—a type of white blood cell within the immune system—mistake the body's own tissues ...

International team discovers likely basis of birth defect causing premature skull closure in infants

2012-11-19

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) -- An international team of geneticists, pediatricians, surgeons and epidemiologists from 23 institutions across three continents has identified two areas of the human genome associated with the most common form of non-syndromic craniosynostosis ― premature closure of the bony plates of the skull.

"We have discovered two genetic factors that are strongly associated with the most common form of premature closure of the skull," said Simeon Boyadjiev, professor of pediatrics and genetics, principal investigator for the study and leader of the International ...

Skin cells reveal DNA's genetic mosaic

2012-11-19

The prevailing wisdom has been that every cell in the body contains identical DNA. However, a new study of stem cells derived from the skin has found that genetic variations are widespread in the body's tissues, a finding with profound implications for genetic screening, according to Yale School of Medicine researchers.

Published in the Nov. 18 issue of Nature, the study paves the way for assessing the extent of gene variation, and for better understanding human development and disease.

"We found that humans are made up of a mosaic of cells with different genomes," ...

Optogenetics illuminates pathways of motivation through brain, Stanford study shows

2012-11-19

STANFORD, Calif. — Whether you are an apple tree or an antelope, survival depends on using your energy efficiently. In a difficult or dangerous situation, the key question is whether exerting effort — sending out roots in search of nutrients in a drought or running at top speed from a predator — will be worth the energy.

In a paper to be published online Nov. 18 in Nature, Karl Deisseroth, MD, PhD, a professor of bioengineering and of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University, and postdoctoral scholar Melissa Warden, PhD, describe how they have isolated ...

Stanford/Yale study gives insight into subtle genomic differences among our own cells

2012-11-19

STANFORD, Calif. — Stanford University School of Medicine scientists have demonstrated, in a study conducted jointly with researchers at Yale University, that induced-pluripotent stem cells — the embryonic-stem-cell lookalikes whose discovery a few years ago won this year's Nobel Prize in medicine — are not as genetically unstable as was thought.

The new study, which will be published online Nov. 18 in Nature, showed that what seemed to be changes in iPS cells' genetic makeup — presumed to be inflicted either in the course of their generation from adult cells or during ...

Daycare has many benefits for children, but researchers find mysterious link with overweight

2012-11-19

Young children who attend daycare on a regular basis are 50% more likely to be overweight compared to those who stayed at home with their parents, according to a study by researchers at the University of Montreal and the CHU Sainte-Justine Hospital Research Centre. "We found that children whose primary care arrangement between 1.5 and 4 years was in daycare-center or with an extended family member were around 50% more likely to be overweight or obese between the ages of 4-10 years compared to those cared for at home by their parents," said Dr. Marie-Claude Geoffroy, who ...

Decreased kidney function leads to decreased cognitive functioning

2012-11-19

Decreased kidney function is associated with decreased cognitive functioning in areas such as global cognitive ability, abstract reasoning and verbal memory, according to a study led by Temple University. This is the first study describing change in multiple domains of cognitive functioning in order to determine which specific abilities are most affected in individuals with impaired renal function.

Researchers from Temple, University of Maine and University of Maryland examined longitudinal data, five years apart, from 590 people. They wanted to see how much kidney function ...