(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA – A pathway called the "Unfolded Protein Response," or UPR, a cell's way of responding to unfolded and misfolded proteins, helps tumor cells escape programmed cell death during the development of lymphoma.

Research, led by Lori Hart, Ph.D., research associate and Constantinos Koumenis, Ph.D., associate professor,and research division director in the Department of Radiation Oncology, both from the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and Davide Ruggero, Ph.D., associate professor, Department of Urology, University of California, San Francisco, shows for the first time that the UPR is active in patients with human lymphomas and mice genetically bred to develop lymphomas. Importantly, when the UPR is inactivated, lymphoma cells readily undergo cell death. Their findings appear online in the Journal of Clinical Investigation and will appear in the December 2012 issue.

"The general implications of our work are that components of this pathway may be attractive anti-tumor targets, especially in lymphomas," says Koumenis. "Indeed, an enzyme called PERK, a kinase that we found to play a central role in UPR, is already being targeted by several groups, in academia and pharmaceutical companies with specific inhibitors."

The cancer-causing gene c-Myc paradoxically activates both cell proliferation and death. When the cell becomes cancerous, c-Myc–induced death is bypassed, promoting tumor formation. "A critical feature of c-Myc-overexpressing cells is an increased rate of protein synthesis that is essential for Myc's ability to cause cancer," says Tom Cunningham, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in the Ruggero lab. "Myc tumor cells use this aberrant production of proteins to block apoptosis and activate the UPR. These cancer cells depend on Myc-induced increases in protein abundance to survive. Therefore, targeting protein synthesis downstream of Myc oncogenic activity may represent a promising new therapeutic window for cancer treatment," adds Ruggero.

The accumulation of unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum, an inner cell component where newly made proteins are folded, initiates a stress program, the UPR, to support cell survival. Normally, UPR kicks in when there is an imbalance in the number of proteins that need to be folded and chaperones, specialized proteins that help fold them.

Analysis of mouse and human lymphomas demonstrated significantly higher levels of UPR activation compared with normal tissues. Using multiple genetic models, the two teams, in collaboration with additional labs in the US and Europe, demonstrated that Myc specifically activated one arm of the UPR, leading to increased cell survival by autophagy.

Autophagy is a survival pathway allowing a cell to recycle damaged proteins when it's under stress and reuse the damaged parts to fuel further growth. Cancer cells might be addicted to autophagy, since this innate response may be a critical means by which the cells survive the nutrient limitation and lack of oxygen commonly found within tumors.

Inhibition of one protein, PERK, in the UPR arm studied, significantly reduced Myc-induced autophagy and tumor formation. What's more, drug- or genetic-mediated inhibition of autophagy increased Myc-dependent cell death.

"Our findings establish a role for UPR as an enhancer of c-Myc–induced lymphomas and suggest that inhibiting UPR may be particularly effective against cancers characterized by c-Myc overexpression," says Koumenis. "In this context the UPR essentially acts as one of the cell's rheostats to counterbalance Myc's runaway cell replication nature and its pro-cell-death tendencies."

However, Koumenis indicates that further research is needed on the potential effects of PERK inhibition on normal tissues: "Although data from our lab and other groups suggest that PERK inhibition in tumors grown in animals is feasible, other studies suggest that PERK plays a critical role in the function of secretory tissues such as the pancreas. Carefully testing the effects of new PERK inhibitors in animal models of lymphoma and other malignancies in the next couple of years should address this question and could open the way for new clinical trials with such agents."

INFORMATION:

Funding for this research came from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar, America Cancer Society grant 121364-PF-11-184-01-TBG; and National Cancer Institute grants R01 CA094214; R01 CA139362; and R01 CA140456.

This work included several laboratories, including those of Alan Diehl and Serge Fuchs, both from Penn; Andrei Thomas-Tikhonenko from CHOP and Penn; and Ian Mills from the Oslo University Hospital.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $4.3 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine is currently ranked #2 in U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $479.3 million awarded in the 2011 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania -- recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center; and Pennsylvania Hospital — the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Penn Medicine also includes additional patient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2011, Penn Medicine provided $854 million to benefit our community.

Pathway identified in human lymphoma points way to new blood cancer treatments

2012-11-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

University of Tennessee study: Unexpected microbes fighting harmful greenhouse gas

2012-11-21

The environment has a more formidable opponent than carbon dioxide. Another greenhouse gas, nitrous oxide, is 300 times more potent and also destroys the ozone layer each time it is released into the atmosphere through agricultural practices, sewage treatment and fossil fuel combustion.

Luckily, nature has a larger army than previously thought combating this greenhouse gas—according to a study by Frank Loeffler, University of Tennessee, Knoxville–Oak Ridge National Laboratory Governor's Chair for Microbiology, and his colleagues.

The findings are published in the ...

Saving water without hurting peach production

2012-11-21

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists are helping peach growers make the most of dwindling water supplies in California's San Joaquin Valley.

Agricultural Research Service (ARS) scientist James E. Ayars at the San Joaquin Valley Agricultural Sciences Center in Parlier, Calif., has found a way to reduce the amount of water given post-harvest to early-season peaches so that the reduction has a minimal effect on yield and fruit quality. ARS is USDA's principal intramural scientific research agency, and the research supports the USDA priority of promoting international ...

Better protection for forging dies

2012-11-21

Forging dies must withstand a lot. They must be hard so that their surface does not get too worn out and is able to last through great changes in temperature and handle the impactful blows of the forge. However, the harder a material is, the more brittle it becomes - and forging dies are less able to handle the stress from the impact. For this reason, the manufacturers had to find a compromise between hardness and strength. One of the possibilities is to surround a semi-hard, strong material with a hard layer. The problem is that the layer rests on the softer material and ...

CDC and NIH survey provides first report of state-level COPD prevalence

2012-11-21

The age-adjusted prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) varies considerably within the United States, from less than 4 percent of the population in Washington and Minnesota to more than 9 percent in Alabama and Kentucky. These state-level rates are among the COPD data available for the first time as part of the newly released 2011 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey.

"COPD is a tremendous public health burden and a leading cause of death. It is a health condition that needs to be urgently addressed, particularly on a local level," ...

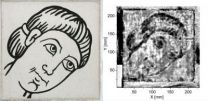

Detective work using terahertz radiation

2012-11-21

It was a special moment for Michael Panzner of the Fraunhofer Institute for Material and Beam Technology IWS in Dresden, Germany and his partners: in the Dresden Hygiene Museum the scientists were examining a wall picture by Gerhard Richter that had been believed lost long ago. Shortly before leaving the German Democratic Republic the artist had left it behind as a journeyman's project. Then, in the 1960s, it was unceremoniously painted over. However, instead of being interested in the picture, Panzer was far more interested in the new detector which was being used for ...

Architecture of rod sensory cilium disrupted by mutation

2012-11-21

HOUSTON – (Nov. 22, 2012) – Using a new technique called cryo-electron tomography, two research teams at Baylor College of Medicine (www.bcm.edu) have created a three-dimensional map that gives a better understanding of how the architecture of the rod sensory cilium (part of one type of photoreceptor in the eye) is changed by genetic mutation and how that affects its ability to transport proteins as part of the light-sensing process.

Almost all mammalian cells have cilia. Some are motile and some are not. They play a central role in cellular operations, and when they ...

New evidence of dinosaurs' role in the evolution of bird flight

2012-11-21

Academics at the Universities of Bristol, Yale and Calgary have shown that prehistoric birds had a much more primitive version of the wings we see today, with rigid layers of feathers acting as simple airfoils for gliding.

Close examination of the earliest theropod dinosaurs suggests that feathers were initially developed for insulation, arranged in multiple layers to preserve heat, before their shape evolved for display and camouflage.

As evolution changed the configuration of the feathers, their important role in the aerodynamics and mechanics of flight became more ...

New Informatics and Bioimaging Center combines resources, expertise from UMD, UMB

2012-11-21

ADELPHI, Md. – A new center that combines advanced computing resources at the University of Maryland, College Park (UMD) with clinical data and biomedical expertise at the University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB) could soon revolutionize the efficiency and effectiveness of health care in the state of Maryland and beyond.

The Center for Health-related Informatics and Bioimaging (CHIB) announced today joins computer scientists, life scientists, engineers, physicists, biostatisticians and others at the College Park campus with imaging specialists, physicians, clinicians ...

Wormholes from centuries-old art prints reveal the history of the 'worms'

2012-11-21

By examining art printed from woodblocks spanning five centuries, Blair Hedges, a professor of biology at Penn State University, has identified the species responsible for making the ever-present wormholes in European printed art since the Renaissance. The hole-makers, two species of wood-boring beetles, are widely distributed today, but the "wormhole record," as Hedges calls it, reveals a different pattern in the past, where the two species met along a zone across central Europe like a battle line of two armies. The research, which is the first of its kind to use printed ...

Human obedience: The myth of blind conformity

2012-11-21

In the 1960s and 1970s, classic social psychological studies were conducted that provided evidence that even normal, decent people can engage in acts of extreme cruelty when instructed to do so by others. However, in an essay published November 20 in the open access journal PLOS Biology, Professors Alex Haslam and Stephen Reicher revisit these studies' conclusions and explain how awful acts involve not just obedience, but enthusiasm too—challenging the long-held belief that human beings are 'programmed' for conformity.

This belief can be traced back to two landmark empirical ...