(Press-News.org) A study dating the age of more than 1 million single-letter variations in the human DNA code reveals that most of these mutations are of recent origin, evolutionarily speaking. These kinds of mutations change one nucleotide – an A, C, T or G – in the DNA sequence. Over 86 percent of the harmful protein-coding mutations of this type arose in humans just during the past 5,000 to 10,000 years.

Some of the remaining mutations of this nature may have no effect on people, and a few might be beneficial, according to the project researchers. While each specific mutation is rare, the findings suggest that the human population acquired an abundance of these single-nucleotide genetic variants in a relatively short time.

"The spectrum of human diversity that exists today is vastly different than what it was only 200 to 400 generations ago," said Dr. Joshua Akey, associate professor of genome sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle. He is one of several leaders of a multi-institutional effort among evolutionary geneticists to date the first appearance of a multitude of single nucleotide variants in the human population.

Their findings appear in the Nov. 28 edition of Nature. The lead author is Dr. Wenqing Fu of the UW Department of Genome Sciences.

The work stems from collaboration among many genome scientists, medical geneticists, molecular biologists and biostatisticians at the UW, the University of Michigan, Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, the Broad Institute at MIT and Harvard, and the Population Genetics Working Group. The study is part of the Exome Sequencing Project of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

To place this discovery in the context of the prehistory and ancient history of people, humans have been around for roughly 100,000 years. In the Middle East, cities formed nearly 8,500 years ago, and writing was used in Mesopotamia at least 5,500 years ago.

The researchers assessed the distribution of mutation ages by re-sequencing 15,336 protein-coding genes in 6,515 people. Of them, 4,298 were of European ancestry, and 2,217 were African.

The researchers based their explanation for the enormous excess of rare genetic variants in the present-day population on the Out-of-Africa model of the human diaspora to other parts of the world.

"On average, each person has about 150 new mutations not found in either of their parents," Akey said. "The number of such genetic changes introduced into a population depends on its size."

Larger populations, continuing to multiply by producing children, have more opportunities for new mutations to appear. The number of mutations thereby increases with accelerated population growth, such as the population explosion that began 5,115 years ago.

During the Out of Africa migration of some early humans into Europe and beyond some 50,000 years past, a population bottleneck occurred: The number of humans plummeted, and the shrinking remnant became more genetically similar. Back then, mutations that were only slightly damaging had a greater probability of being carried from one generation to the next, Akey explained.

"Those mutations don't influence the ability to survive and reproduce," he said. "The Out of Africa bottleneck led to inefficient purging of the less-harmful mutations."

His group found that, compared to Africans, people of European descent had an excess of harmful mutations in essential genes, which are those required to grow to adulthood and have offspring, and in genes linked to Mendelian, or single-mutation diseases.

The study team also observed that the older the genetic variant, the less likely it was to be deleterious. In addition, certain genes, they learned, harbored only younger, more damaging, mutations that surfaced less than 5,000 years ago. These include 12 genes linked to such diseases as premature ovarian failure, Alzheimer's, hardening of the heart arteries, and an inherited form of paralysis.

Overall, the researchers predicted that about 81 percent of the single-nucleotide variants in their European samples, and 58 percent in their African samples, arose in the past 5,000 years. Older single- nucleotide variants – first appearing longer than 50,000 years ago – were more frequent in African samples.

The scientists also noted that mutations affecting genes involved in metabolic pathways – chemical reactions in the body to generate and tap energy – tended not to be weeded out by selective forces. Aberrant metabolism contributes to diabetes, lipid disorders, obesity, and insulin resistance – all common, modern scourges.

The researchers pointed out that the results illustrate the profound effect recent human evolutionary history has had on the burden of damaging mutations in contemporary populations.

"The historical details of human protein-coding variation provide practical information for prioritizing approaches to disease gene discovery," Akey said.

Although the enlarged mutational capacity resulting from population growth has led to a greater incidence of genetic disorders among the world's 7 billion people, there is brighter side to the story.

Mutations have fostered the great variety of traits seen among modern humans, according to the researchers, who added, "They also may have created a new repository of advantageous genetic variants that adaptive evolution may act upon in future generations."

INFORMATION:

Most of the harmful mutations in people arose in the past 5,000 to 10,000 years

Spectrum of human genetic diversity today is vastly different from only 200 to 400 generations ago

2012-11-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Alcoholic fly larvae need fix for learning

2012-11-29

Fly larvae fed on alcohol-spiked food for a period of days grow dependent on those spirits for learning. The findings, reported in Current Biology, a Cell Press publication, on November 29th, show how overuse of alcohol can produce lasting changes in the brain, even after alcohol abuse stops.

The report also provides evidence that the very human experience of alcoholism can be explored in part with studies conducted in fruit flies and other animals, the researchers say.

"Our evidence supports the long-ago proposed idea that functional ethanol tolerance is produced by ...

Hand use improved after spinal cord injury with noninvasive stimulation

2012-11-29

By using noninvasive stimulation, researchers were able to temporarily improve the ability of people with spinal cord injuries to use their hands. The findings, reported on November 29th in Current Biology, a Cell Press publication, hold promise in treating thousands of people in the United States alone who are partially paralyzed due to spinal cord injury.

"This approach builds on earlier work and highlights the importance of the corticospinal tract—which conducts impulses from the brain's motor cortex to the spinal cord and is a major pathway contributing to voluntary ...

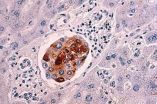

Traffic cops of the immune system

2012-11-29

This press release is available in German.

Now, scientists at the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI) have looked into the origin of Tregs and uncovered a central role played by the protein IkBNS. Armed with this knowledge, the researchers hope to manipulate Tregs in order to either inhibit or activate the immune system. Biochemist Prof. Ingo Schmitz and his team have now published their findings in the scientific journal Immunity.

The immune system is a complex network of different types of cells and chemical messengers. The regulatory cells and other immune ...

UW-Madison scientists create roadmap to metabolic reprogramming for aging

2012-11-29

MADISON – In efforts to understand what influences life span, cancer and aging, scientists are building roadmaps to navigate and learn about cells at the molecular level.

To survey previously uncharted territory, a team of researchers at UW-Madison created an "atlas" that maps more than 1,500 unique landmarks within mitochondria that could provide clues to the metabolic connections between caloric restriction and aging.

The map, as well as the techniques used to create it, could lead to a better understanding of how cell metabolism is re-wired in some cancers, age-related ...

Study helps resolve debate about how tumors spread

2012-11-29

A team of scientists, led by researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, has shown for the first time how cancer cells control the ON/OFF switch of a program used by developing embryos to effectively metastasize in vivo, breaking free and spreading to other parts of the body, where they can proliferate and grow into secondary tumors.

The findings are published in the December 11 issue of the journal Cancer Cell.

In 90 percent of cancer deaths, it is the spreading of cancer, known as metastasis, which ultimately kills the patient by impacting ...

Study sheds light on how pancreatic cancer begins

2012-11-29

A diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is particularly devastating since the prognosis for recovery is usually poor, with the cancer most often not detected until late stages.

Research led by scientists at the University of California, San Diego and UC San Francisco Schools of Medicine examined the tumor-initiating events leading to pancreatic cancer (also called pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma or PDA) in mice. Their work, published on line November 29 in the journal Cancer Cell, may help in the search for earlier detection methods and treatments.

"Previously, it was believed ...

Short-term exposure to essential oils lowers blood pressure and heart rate

2012-11-29

The scents which permeate our health spas from aromatic essential oils may provide more benefits than just a sense of rest and well-being.

For according to a new study(1) in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, the essential oils which form the basis of aromatherapy for stress relief are also reported to have a beneficial effect on heart rate and blood pressure following short-term exposure - and may therefore reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. However, on the downside, those beneficial effects were reversed when exposure to essential oils lasted more ...

Prenatal exposure to testosterone leads to verbal aggressive behavior

2012-11-29

Washington, DC (November 27, 2012) –A new study in the Journal of Communication links verbal aggression to prenatal testosterone exposure. The lead researcher, at University at Buffalo – The State University of New York, used the 2D:4D measure to predict verbal aggression. This study is the first to use this method to examine prenatal testosterone exposure as a determinant of a communication trait.

Allison Z. Shaw, University at Buffalo – The State University of New York, Michael R. Kotowski, University of Tennessee, and Franklin J. Boster and Timothy R. Levine, Michigan ...

Enzyme inhibition protects against Huntington's disease damage in 2 animal models

2012-11-29

Treatment with a novel agent that inhibits the activity of SIRT2, an enzyme that regulates many important cellular functions, reduced neurological damage, slowed the loss of motor function and extended survival in two animal models of Huntington's disease. The study led by Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) researchers will appear in the Dec. 27 issue of Cell Reports and is receiving advance online release.

"I believe that the drug efficacy demonstrated in two distinct genetic HD mouse models is quite unique and highly encouraging," says Aleksey Kazantsev, PhD, of ...

Biology behind brain development disorder

2012-11-29

Researchers have defined the gene responsible for a rare developmental disorder in children. The team showed that rare variation in a gene involved in brain development causes the disorder. This is the first time that this gene, UBE3B, has been linked to a disease.

By using a combination of research in mice and sequencing the DNA of four patients with the disorder, the team showed that disruption of this gene causes symptoms including brain abnormalities and reduced growth, highlighting the power of mouse models for understanding the biology behind rare diseases.

"Ubiquitination, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

[Press-News.org] Most of the harmful mutations in people arose in the past 5,000 to 10,000 yearsSpectrum of human genetic diversity today is vastly different from only 200 to 400 generations ago