(Press-News.org) Solvents are omnipresent in the chemical industry, and are a major environmental and safety concern. Therefore the large interest in mechanochemistry: an energy-efficient alternative that avoids using bulk solvents and uses high-frequency milling to drive reactions. Milling is achieved by the intense impact of steel balls in a rapidly moving jar, which hinders the direct observation of underlying chemistry. Scientists have now for the first time studied a milling reaction in real time, using highly penetrating X-rays to observe the surprisingly rapid transformations as the mill mixes, grinds and transforms simple ingredients into a complex product. This study opens new opportunities in Green Chemistry and environmentally-friendly synthesis. The results are published in Nature Chemistry dated 2 December 2012.

The international team of scientists was led by Tomislav Friščić of McGill University (Canada) in collaboration with Ivan Halasz from the University of Zagreb (Croatia), scientists from the University of Cambridge (UK), Max-Planck-Institute for Solid State Research in Stuttgart (Germany) and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble (France).

Everybody remembering their chemistry lessons will recall mixing ingredients into a solvent. This was sometimes water, but more often a solvent such as ether (flammable), chloroform (toxic) or benzene (cancerogenic). Bulk solvents used in industry pose a serious threat to human health and the environment, and their responsible management has a considerable cost. Although it is well known that mechanical action can break chemical bonds, for example in tear and wear of textile fibres, it is much less known that mechanical force can also be used to synthesize new chemical compounds and materials. In recent years, ball milling has become increasingly popular in the production of highly complex chemical structures. In such synthesis, steel balls are shaken with the reactants and catalysts in a rapidly vibrating jar. Chemical transformations take place at the sites of ball collision, where impact causes instant "hot spots" of localized heat and pressure. This is difficult to model and, without access to real time reaction monitoring, mechanochemistry remained poorly understood. "When we set out to study these reactions, the challenge was to observe the entire reaction without disturbing it, in particular the short-lived intermediates that appear and disappear under continuous impact in less than a minute", says Tomislav Friščić, a Professor at McGill University in Montreal.

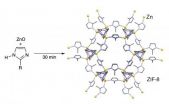

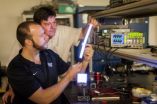

The team of scientists chose to study mechanochemical production of the metal-organic framework ZIF-8 (sold as Basolite Z1200) from the simplest and non-toxic components. Materials such as ZIF-8 are rapidly gaining popularity for capturing large amounts of CO2 and, if manufactured cheaply and sustainably, could become widely used for carbon capture, catalysis and even hydrogen storage. "The team came to the ESRF because of our high-energy X-rays capable of penetrating 3 mm thick walls of a rapidly moving reaction jar made of steel, aluminium or plastic. The X-ray beam must get inside the jar to probe the mechanochemical formation of ZIF-8, and then out again to detect the changes as they happened", says Simon Kimber, a scientist at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, who is a member of the team. This unprecedented methodology enabled the real-time observation of reaction kinetics, reaction intermediates and the development of their respective nanoparticles.

This technique is not limited to ZIF-8. In principle, all types of chemical reactions in a ball mill can now be studied and optimized for industrial processing. 'These results hold promise for improving the fundamental understanding of processes central to pharmaceutical, metallurgical, cement and mineral industries and should enable a more efficient use of energy, reduction in solvent and optimize the use of often expensive catalysts. This translates into good news for the environment, the industry and the consumers who will have to pay less", concludes Tomislav Friščić.

INFORMATION:

A shock to pollution in chemistry

X-rays help understand how mechanical action can lead to greener chemistry

2012-12-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Cell surface transporters exploited for cancer drug delivery

2012-12-03

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (December 2, 2012) –Whitehead Institute scientists report that certain molecules present in high concentrations on the surfaces of many cancer cells could be exploited to funnel lethal toxic molecules into the malignant cells. In such an approach, the overexpression of specific transporters could be exploited to deliver toxic substances into cancer cells.

Although this finding emerges from the study of a single toxic molecule and the protein that it transports, Whitehead Member David Sabatini says this phenomenon could be leveraged more broadly.

"Our ...

Surprising results from study of non-epileptic seizures

2012-12-03

MAYWOOD, Il. - A Loyola University Medical Center neurologist is reporting surprising results of a study of patients who experience both epileptic and non-epileptic seizures.

Non-epileptic seizures resemble epileptic seizures, but are not accompanied by abnormal electrical discharges. Rather, these seizures are believed to be brought on by psychological stresses.

Dr. Diane Thomas reported that 15.7 percent of hospital patients who experienced non-epileptic seizures also had epileptic seizures during the same hospital stay. Previous studies found the percentage of such ...

A better way to make chemicals?

2012-12-03

Bulk solvents, widely used in the chemical industry, pose a serious threat to human health and the environment. As a result, there is growing interest in avoiding their use by relying on "mechanochemistry" – an energy-efficient alternative that uses high-frequency milling to drive reactions. Because milling involves the intense impact of steel balls in rapidly moving jars, however, the underlying chemistry is difficult to observe.

Now, for the first time, scientists have studied a milling reaction in real time, using highly penetrating X-rays to observe the surprisingly ...

Glowing fish shed light on metabolism

2012-12-03

A tiny, translucent zebrafish that glows green when its liver makes glucose has helped an international team of researchers identify a compound that regulates whole-body metabolism and appears to protect obese mice from signs of metabolic disorders.

Led by scientists at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), the work demonstrates how a fish smaller than a grain of rice can help screen for drugs to help control obesity, type 2 diabetes and other metabolic disorders, which affect a rising 34 percent of American adults and are major risk factors for cardiovascular ...

Stanford researchers discover master regulator of skin development

2012-12-03

STANFORD, Calif. — The surface of your skin, called the epidermis, is a complex mixture of many different cell types — each with a very specific job. The production, or differentiation, of such a sophisticated tissue requires an immense amount of coordination at the cellular level, and glitches in the process can have disastrous consequences. Now, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have identified a master regulator of this differentiation process.

"Disorders of epidermal differentiation, from skin cancer to eczema, will affect roughly one-half ...

International study points to inflammation as a cause of plaque buildup in heart vessels

2012-12-03

STANFORD, Calif. — Fifteen new genetic regions associated with coronary artery disease have been identified by a large, international consortium of scientists — including researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine — taking a significant step forward in understanding the root causes of this deadly disease. The new research brings the total number of validated genetic links with heart disease discovered through genome-wide association studies to 46.

Coronary artery disease is the process by which plaque builds up in the wall of heart vessels, eventually leading ...

Goodbye, fluorescent light bulbs! See your office in a new light

2012-12-03

Say goodbye to that annoying buzz created by overhead fluorescent light bulbs in your office. Scientists at Wake Forest University have developed a flicker-free, shatterproof alternative for large-scale lighting.

The lighting, based on field-induced polymer electroluminescent (FIPEL) technology, also gives off soft, white light – not the yellowish glint from fluorescents or bluish tinge from LEDs.

"People often complain that fluorescent lights bother their eyes, and the hum from the fluorescent tubes irritates anyone sitting at a desk underneath them," said David Carroll, ...

Common diabetes drug may help treat ovarian cancer

2012-12-03

A new study suggests that the common diabetes medication metformin may be considered for use in the prevention or treatment of ovarian cancer. Published early online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society, the study found that ovarian cancer patients who took the drug tended to live longer than patients who did not take it.

New treatments are desperately needed for ovarian cancer. Previous research has indicated that metformin, which originates from the French Lilac plant, may have anticancer properties. To look for an effect of the medication ...

Food allergies? Pesticides in tap water might be to blame

2012-12-03

ARLINGTON HEIGHTS, Ill. (December 3, 2012) – Food allergies are on the rise, affecting 15 million Americans. And according to a new study published in the December issue of Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, the scientific journal of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI), pesticides and tap water could be partially to blame.

The study reported that high levels of dichlorophenols, a chemical used in pesticides and to chlorinate water, when found in the human body, are associated with food allergies.

"Our research shows that high levels ...

Mayo study: Common diabetes drug may treat ovarian cancer

2012-12-03

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- Diabetic patients with ovarian cancer who took the drug metformin for their diabetes had a better survival rate than patients who did not take it, a study headed by Mayo Clinic shows. The findings, published early online in the journal Cancer, may play an important role for researchers as they study the use of existing medications to treat different or new diseases.

Metformin is a widely prescribed drug to treat diabetes, and previous research by others has shown its promise for other cancers. The Mayo-led study adds ovarian cancer to the list.

Researchers ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

GLP-1 drugs associated with reduced need for emergency care for migraine

New knowledge on heritability paves the way for better treatment of people with chronic inflammatory bowel disease

Under the Lens: Microbiologists Nicola Holden and Gil Domingue weigh in on the raw milk debate

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

[Press-News.org] A shock to pollution in chemistryX-rays help understand how mechanical action can lead to greener chemistry