(Press-News.org) In a genome sequencing study of 74 neuroblastoma tumors in children, scientists at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) found that patients with changes in two genes, ARID1A and ARID1B, survive only a quarter as long as patients without the changes. The discovery could eventually lead to early identification of patients with aggressive neuroblastomas who may need additional treatments.

Neuroblastomas affect nerve tissue throughout the body and are the most common, non-blood cancer in children. "These cancers have a wide spectrum of clinical outcomes, with some that are highly curable and others very lethal," says Victor Velculescu, M.D., Ph.D., professor of oncology and co-director of the Cancer Biology Program at Johns Hopkins. "Part of the reason for this variety in prognosis may be due to changes in the ARID1A and ARID1B genes."

Velculescu said these powerful "bully" genes were not identified in other gene sequencing studies of neuroblastoma, most likely because the Johns Hopkins-CHOP researchers used sequencing and analytical methods that looked for larger, structural rearrangements of DNA in addition to changes in the sequence of individual chemical base-pairs that form DNA. A report of their work appears in the Dec. 2 issue of Nature Genetics.

Of the 74 tumors in the study, 71 were analyzed for both rearrangements and base-pair changes. Cancer-specific mutations were found in a variety of genes previously linked to neuroblastoma, including the ALK and MYCN genes. In eight of the 71 patients, the investigators found alterations in the ARID1A and ARID1B genes, which normally control the way DNA folds to allow or block protein production.

The children with ARID1A or ARID1B gene changes had far worse survival, on average, than those without the genetic alterations — 386 days compared with 1,689 days. All but one of these patients died of progressive disease, including one child whose neuroblastoma was thought to be highly curable.

The scientists were also able to detect and monitor neuroblastoma-specific genetic changes in the blood of four patients included in the study, and correlated these findings to disease progression.

"Finding cancer-specific alterations in the blood could help clinicians monitor patients for relapse and determine whether residual cancer cells remain in the body after surgery," says Mark Sausen, a Johns Hopkins graduate student and one of the lead scientists involved in the research.

The Johns Hopkins-CHOP team plans to conduct further studies in larger groups of patients to confirm the ARID1A-ARID1B correlation to prognosis.

INFORMATION:

Funding for the study was provided by the St. Baldrick's Foundation, the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, Swim Across America, the American Association for Cancer Research – Stand Up To Cancer's Dream Team Translational Cancer Research Grant, and the National Institutes of Health's National Cancer Institute (CA121113).

In addition to Velculescu and Sausen, scientists involved in the research include Rebecca Leary, Sian Jones, Jian Wu, Amanda Blackford, Luis Diaz, Nickolas Papadopoulos, Bert Vogelstein, and Kenneth Kinzler from Johns Hopkins; C. Patrick Reynolds from Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center; Giovanni Parmigiani from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; and Michael Hogarty and Xueyuan Liu from the Childrens Hospital of Philadelphia.

Papadopoulos, Kinzler, Vogelstein, Diaz and Velculescu are co-founders of Inostics and Personal Genome Diagnostics and are members of the companies' Scientific Advisory Boards. They own Inostics and Personal Genome Diagnostics stock, which is subject to certain restrictions under Johns Hopkins University policy. The terms of these arrangements are managed by The Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies.

Media Contacts:

Vanessa Wasta, 410-614-2916, wasta@jhmi.edu

Amy Mone, 410-614-2915, amone1@jhmi.edu

END

Scientists have discovered for the first time how humans – and other mammals – have evolved to have intelligence.

Researchers have identified the moment in history when the genes that enabled us to think and reason evolved.

This point 500 million years ago provided our ability to learn complex skills, analyse situations and have flexibility in the way in which we think.

Professor Seth Grant, of the University of Edinburgh, who led the research, said: "One of the greatest scientific problems is to explain how intelligence and complex behaviours arose during evolution." ...

This press release is available in German.

Abused children are at high risk of anxiety and mood disorders, as traumatic experience induces lasting changes to their gene regulation. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry in Munich have now documented for the first time that genetic variants of the FKBP5 gene can influence epigenetic alterations in this gene induced by early trauma. In individuals with a genetic predisposition, trauma causes long-term changes in DNA methylation leading to a lasting dysregulation of the stress hormone system. As a result, ...

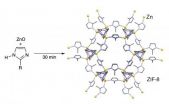

Solvents are omnipresent in the chemical industry, and are a major environmental and safety concern. Therefore the large interest in mechanochemistry: an energy-efficient alternative that avoids using bulk solvents and uses high-frequency milling to drive reactions. Milling is achieved by the intense impact of steel balls in a rapidly moving jar, which hinders the direct observation of underlying chemistry. Scientists have now for the first time studied a milling reaction in real time, using highly penetrating X-rays to observe the surprisingly rapid transformations as ...

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (December 2, 2012) –Whitehead Institute scientists report that certain molecules present in high concentrations on the surfaces of many cancer cells could be exploited to funnel lethal toxic molecules into the malignant cells. In such an approach, the overexpression of specific transporters could be exploited to deliver toxic substances into cancer cells.

Although this finding emerges from the study of a single toxic molecule and the protein that it transports, Whitehead Member David Sabatini says this phenomenon could be leveraged more broadly.

"Our ...

MAYWOOD, Il. - A Loyola University Medical Center neurologist is reporting surprising results of a study of patients who experience both epileptic and non-epileptic seizures.

Non-epileptic seizures resemble epileptic seizures, but are not accompanied by abnormal electrical discharges. Rather, these seizures are believed to be brought on by psychological stresses.

Dr. Diane Thomas reported that 15.7 percent of hospital patients who experienced non-epileptic seizures also had epileptic seizures during the same hospital stay. Previous studies found the percentage of such ...

Bulk solvents, widely used in the chemical industry, pose a serious threat to human health and the environment. As a result, there is growing interest in avoiding their use by relying on "mechanochemistry" – an energy-efficient alternative that uses high-frequency milling to drive reactions. Because milling involves the intense impact of steel balls in rapidly moving jars, however, the underlying chemistry is difficult to observe.

Now, for the first time, scientists have studied a milling reaction in real time, using highly penetrating X-rays to observe the surprisingly ...

A tiny, translucent zebrafish that glows green when its liver makes glucose has helped an international team of researchers identify a compound that regulates whole-body metabolism and appears to protect obese mice from signs of metabolic disorders.

Led by scientists at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), the work demonstrates how a fish smaller than a grain of rice can help screen for drugs to help control obesity, type 2 diabetes and other metabolic disorders, which affect a rising 34 percent of American adults and are major risk factors for cardiovascular ...

STANFORD, Calif. — The surface of your skin, called the epidermis, is a complex mixture of many different cell types — each with a very specific job. The production, or differentiation, of such a sophisticated tissue requires an immense amount of coordination at the cellular level, and glitches in the process can have disastrous consequences. Now, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have identified a master regulator of this differentiation process.

"Disorders of epidermal differentiation, from skin cancer to eczema, will affect roughly one-half ...

STANFORD, Calif. — Fifteen new genetic regions associated with coronary artery disease have been identified by a large, international consortium of scientists — including researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine — taking a significant step forward in understanding the root causes of this deadly disease. The new research brings the total number of validated genetic links with heart disease discovered through genome-wide association studies to 46.

Coronary artery disease is the process by which plaque builds up in the wall of heart vessels, eventually leading ...

Say goodbye to that annoying buzz created by overhead fluorescent light bulbs in your office. Scientists at Wake Forest University have developed a flicker-free, shatterproof alternative for large-scale lighting.

The lighting, based on field-induced polymer electroluminescent (FIPEL) technology, also gives off soft, white light – not the yellowish glint from fluorescents or bluish tinge from LEDs.

"People often complain that fluorescent lights bother their eyes, and the hum from the fluorescent tubes irritates anyone sitting at a desk underneath them," said David Carroll, ...