(Press-News.org) Stanford geophysicists are well represented at the meeting of the American Geophysical Union this week in San Francisco. Included among the many presentations will be several studies that relate to predicting – and preparing for – major earthquakes in the Himalaya Mountains and the Pacific Northwest.

The AGU Fall Meeting is the largest worldwide conference in the geophysical sciences, attracting more than 20,000 Earth and space scientists, educators, students, and other leaders. This 45th annual fall meeting is taking place through Dec. 7 at the Moscone Convention Center in San Francisco.

A big one in the Himalayas

The Himalayan range was formed, and remains currently active, due to the collision of the Indian and Asian continental plates. Scientists have known for some time that India is subducting under Asia, and have recently begun studying the complexity of this volatile collision zone in greater detail, particularly the fault that separates the two plates, the Main Himalayan Thrust (MHT).

Previous observations had indicated a relatively uniform fault plane that dipped a few degrees to the north. To produce a clearer picture of the fault, Warren Caldwell, a geophysics doctoral student at Stanford, has analyzed seismic data from 20 seismometers deployed for two years across the Himalayas by colleagues at the National Geophysical Research Institute of India.

The data imaged a thrust dipping a gentle two to four degrees northward, as has been previously inferred, but also revealed a segment of the thrust that dips more steeply (15 degrees downward) for 20 kilometers. Such a ramp has been postulated to be a nucleation point for massive earthquakes in the Himalaya.

Although Caldwell emphasized that his research focuses on imaging the fault, not on predicting earthquakes, he noted that the MHT has historically been responsible for a magnitude 8 to 9 earthquake every several hundred years.

"What we're observing doesn't bear on where we are in the earthquake cycle, but it has implications in predicting earthquake magnitude," Caldwell said. "From our imaging, the ramp location is a bit farther north than has been previously observed, which would create a larger rupture width and a larger magnitude earthquake."

Caldwell will present a poster detailing the research on Tuesday, Dec. 4, from 1:40 p.m. to 6 p.m. in Moscone South, Halls A-C.

Caldwell's adviser, geophysics Professor Simon Klemperer, added that recent detections of magma and water around the MHT indicate which segments of the thrust will rupture during an earthquake.

"We think that the big thrust vault will probably rupture southward to the Earth's surface, but we don't expect significant rupture north of there," Klemperer said. The findings are important for creating risk assessments and disaster plans for the heavily populated cities in the region.

Klemperer spoke about the evolution of geophysical studies of the Himalayas today (Dec. 3) from 1:40 p.m. to 3:40 p.m. in Moscone South.

Measuring small tremors in the Pacific Northwest

The Cascadia subduction zone, which stretches from northern California to Vancouver Island, has not experienced a major seismic event since it ruptured in 1700, an 8.7.2 magnitude earthquake that shook the region and created a tsunami that reached Japan. And while many geophysicists believe the fault is due for a similar scale event, the relative lack of any earthquake data in the Pacific Northwest makes it difficult to predict how ground motion from a future event would propagate in the Cascadia area, which runs through Seattle, Portland and Vancouver.

Stanford postdoctoral scholar Annemarie Baltay will present research on how measurements of small seismic tremors in the region can be utilized to determine how ground motion from larger events might behave. Baltay's research involves measuring low amplitude tectonic tremor that occurs 30 kilometers below Earth's surface, at the intersections of tectonic plates, roughly over the course of a month each year.

By analyzing how the tremor signal decays along and away from the Cascadia subduction zone, Baltay can calculate how ground motion activity from a larger earthquake will dissipate. An important application of the work will be to help inform new construction how best to mitigate damage should a large earthquake strike.

"We can't predict when an earthquake will occur, but we can try to be very prepared for them," Baltay said. "Looking at these episodic tremor events can help us constrain what the ground motion might be like in a certain place during an earthquake."

Though Baltay has focused on the Cascadia subduction zone, she said that the technique could be applied in areas of high earthquake risk around the world, such as Alaska and Japan.

Baltay will present a poster presentation of the research on Wednesday (Dec. 5) from 1:40 p.m. to 5:40 p.m in Moscone South, Halls A-C.

Cascadia quake simulations

The slow slip and tremor events in Cascadia are also being studied by Stanford geophysics Professor Paul Segall, although in an entirely different manner. Segall's group uses computational models of the region to determine whether the cumulative effects of many small events can trigger a major earthquake.

"You have these small events every 15 months or so, and a magnitude 9 earthquake every 500 years. We need to known whether you want to raise an alert every time one of these small events happens," Segall said. "We're doing sophisticated numerical calculations to simulate these slow events and see whether they do relate to big earthquakes over time. What our calculations have shown is that ultimately these slow events do evolve into the ultimate fast event, and it does this on a pretty short time scale."

Unfortunately, so far Segall's group has not seen any obvious differences in the numerical simulations between the average slow slip event and those that directly precede a big earthquake. The work is still young, and Segall noted that the model needs refinement to better match actual observations and to possibly identify the signature of the event that triggers a large earthquake.

"We're not so confident in our model that public policy should be based on the output of our calculations, but we're working in that direction," Segall said.

One thing that makes Segall's work difficult is a lack of data from actual earthquakes in the Cascadia region. Earlier this year, however, earthquakes in Mexico and Costa Rica occurred in areas that experience slow slip events similar to those in Cascadia. Segall plans to speak with geophysicists who have studied the lead-up to those earthquakes to compare the data to his simulations.

### Editor Note:

Geophysics Professor Paul Segall will present this work on Thursday (Dec. 6) from 10:20 a.m. to 12:20 p.m. in Moscone South.

Himalayas and Pacific Northwest could experience major earthquakes, Stanford geophysicists say

2012-12-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Method developed by VTT targets diagnosis of early Alzheimer's disease

2012-12-04

A software tool called PredictAD developed by VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland promises to enable earlier diagnosis of the disease on the basis of patient measurements and large databases. Alzheimer's disease currently takes on average 20 months to diagnose in Europe. VTT has shown that the new method could allow as many as half of patients to get a diagnosis approximately a year earlier.

VTT has been studying whether patients suffering from memory problems could be diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease at an earlier stage in the light of their measurement values. ...

Fitness for toad sperm: The secret is to mate frequently

2012-12-04

Fertility tests frequently reveal that males have problems with the quality of their sperm. The problems often relate to sperm senescence, which is a reduction in quality with age. Sperm senescence can arise either before or after the DNA in the sperm cells is produced by a process known as meiosis. So-called "pre-meiotic" senescence results from accumulated damage in the germline cells with increasing age and results in older males having sperm of lower quality. Post-meiotic senescence occurs after the sperm cells have been produced, either during storage of sperm ...

The dance of quantum tornadoes

2012-12-04

Tornado-like vortexes can be produced in bizarre fluids which are controlled by quantum mechanics, completely unlike normal liquids. New research published today in the journal Nature Communications demonstrates how massed ranks of these quantum twisters line up in rows, and paves the way for engineering quantum circuits and chips measuring motion ultra-precisely.

The destructive power of rampaging tornadoes defeats the human ability to control them. A Cambridge team has managed to create and control hundreds of tiny twisters on a semiconductor chip. By controlling where ...

Moderate coffee consumption may reduce risk of diabetes by up to 25 percent

2012-12-04

Drinking three to four cups of coffee per day may help to prevent type 2 diabetes according to research highlighted in a session report published by the Institute for Scientific Information on Coffee (ISIC), a not-for-profit organisation devoted to the study and disclosure of science related to coffee and health.

Recent scientific evidence has consistently linked regular, moderate coffee consumption with a possible reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes. An update of this research and key findings presented during a session at the 2012 World Congress on Prevention ...

Fox invasion threatens wave of extinction, UC research finds

2012-12-04

Using DNA detection techniques developed at the University, the team mapped the presence of foxes in Tasmania, predicted their spread and developed a model of their likely distribution as a blueprint for fox eradication, but swift and decisive action is needed.

University of Canberra professor in wildlife genetics and leader of the team, Stephen Sarre, found foxes are widespread in northern and eastern Tasmania and the model developed by his team forecasts they will spread even further with likely devastating consequences for the island's wildlife.

"There's nothing ...

Ray of hope for human Usher syndrome patients

2012-12-04

After years of basic research, scientists at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) are increasingly able to understand the mechanisms underlying the human Usher syndrome and are coming ever closer to finding a successful treatment approach. The scientists in the Usher research group of Professor Dr. Uwe Wolfrum are evaluating two different strategies. These involve either the repair of mutated genes or the deactivation of the genetic defects using agents. Based on results obtained to date, both options seem promising. Usher syndrome is a congenital disorder that causes ...

New study shows how copper restricts the spread of global antibiotic-resistant infections

2012-12-04

New research from the University of Southampton has shown that copper can prevent horizontal transmission of genes, which has contributed to the increasing number of antibiotic-resistant infections worldwide.

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) in bacteria is largely responsible for the development of antibiotic-resistance, which has led to an increasing number of difficult-to-treat healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs).

The newly-published paper, which appears in the journal mBio, shows that while HGT can take place in the environment, on frequently-touched surfaces, ...

Metabolic biomarkers for preventive molecular medicine

2012-12-04

One of the big challenges of biomedicine is understanding the origin of illnesses in order to improve early detection and significantly increase recovery rates, as well as being able to do what CNIO researchers call preventive molecular medicine, which consists of identifying those individuals who have a greater molecular risk of suffering certain pathologies in order to prevent them. The ageing of the organism, and therefore of the cells and tissues it is made of, represents the greatest risk factor for the majority of developed-world illnesses, including cancer.

A team ...

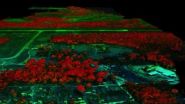

Carnegie debuts revolutionary biosphere mapping capability at AGU

2012-12-04

San Francisco, CA —Researchers from the Carnegie Institution are rolling out results from the new Airborne Taxonomic Mapping System, or AToMS, for the first time at the American Geophysical Union (AGU) meetings in San Francisco. The groundbreaking technology and its scientific observations are uncovering a previously invisible ecological world. To watch a video about how AToMS is helping researchers look at the world in a whole new way, click here.

AToMS, which launched in June 2011, uniquely combines laser and spectral imaging instrumentation onboard a twin-engine aircraft ...

African savannah -- and its lions -- declining at alarming rates

2012-12-04

DURHAM, NC -- About 75 percent of Africa's savannahs and more than two-thirds of the lion population once estimated to live there have disappeared in the last 50 years, according to a study published this week in the journal Biodiversity and Conservation.

The study, led by Duke University researchers, estimates the number of lions now living on the savannahs to be as low as 32,000, down from nearly 100,000 in 1960. Lion populations in West Africa have experienced the greatest declines.

"The word savannah conjures up visions of vast open plains teeming with wildlife. ...