(Press-News.org) Working with mice, Johns Hopkins researchers have shed light on the activity of a protein pair found in cells that form the walls of blood vessels in the brain and retina, experiments that could lead to therapeutic control of the blood-brain barrier and of blood vessel growth in the eye.

Their work reveals a dual role for the protein pair, called Norrin/Frizzled-4, in managing the blood vessel network that serves the brain and retina. The first job of the protein pair's signaling is to form the network's proper 3-D architecture in the retina during fetal development. The second job, after birth, is to continue signaling to maintain the blood-brain barrier, which gives the brain an extra layer of protection against infection transmitted through the circulatory system.

The Hopkins researchers say results of the study, published online in Cell on Dec. 7, could have treatment implications for disorders of the retinal blood vessels caused by diabetes, and age-related loss of central vision. They also could help clinicians develop a way to temporarily increase the penetrability of the blood-brain barrier, allowing critical drugs to pass through to the brain, says Jeremy Nathans, M.D., Ph.D., a Howard Hughes researcher and professor of molecular biology and genetics at the Institute for Basic Biomedical Sciences at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

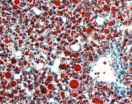

Scientists already knew that Frizzled-4 is a protein located on the surface of the cells that create blood vessel walls throughout the body. Genetic mutations that cause Frizzled-4's absence in mice and humans create severe defects in blood vessel development, but only in the retina, the light-absorbing sheet of cells at the back of the eye. Retinal tissue consumes the most oxygen per gram than any other tissue in the body. Therefore, three networked layers of blood vessels are required to fulfill its oxygen needs. So blood vessel defects in the retina generally starve it of oxygen, causing blindness.

In an effort to understand how Frizzled-4 and its activator Norrin work normally, Nathans' team deleted Norrin in mice. As a result, the rodents' retinal arteries and veins became confused and crisscrossed. Alternatively, if they turned Norrin on earlier than usual, the networks began to develop earlier. And in mice missing either Norrin or Frizzled-4, retinal blood vessels grew radially, but they grew slowly and failed to create the second and third networked layers. All of these results suggest that Norrin and Frizzled-4 play an important role in the proper timing and arrangement of the retinal blood vessel network, Nathans says.

The team also found that mice missing just Frizzled-4, besides having major structural defects in their retinal blood vessels, showed signs of a leaky blood-brain barrier and, similarly, a leaky blood-retina barrier. To get at the cause of this, the team used special genetic tricks to control the activity of Frizzled-4 in a time- and cell-specific manner, creating mice that were missing Frizzled-4 in only about one out of every 20 endothelial cells. What they found is that only the cells missing Frizzled-4 were leaky and, surprisingly, the general architecture of the networks was fine.

Nathans explains that, normally, these blood vessel endothelial cells contain permeable "windows" and relatively loose "bolts" connecting the cells together. When in the brain and retina, they have no "windows" and their "bolts" connect them tightly. Nathans adds, "We now know that endothelial cells that make up the blood-brain barrier have to receive signals constantly from nearby brain or retinal cells telling them, 'You're in the brain. Tighten your bolts and close your windows.'"

The "windows" in the other endothelial cells in the body are protein portals that allow large molecules to pass through easily — to be filtered by the kidneys, for example. The central nervous system, including the retina, is a privileged area. If toxins were to pass through an endothelial "window" into the brain, the resulting damage could be detrimental to the brain's activity. So the body seals off these areas from bloodborne pathogens by tightening the "bolts" between and closing the "windows" of the endothelial cells that form the blood vessels servicing those areas. This reinforcement of the endothelial cells is what is known as the blood-brain barrier.

Although crucial to protecting the central nervous system, the blood-brain barrier also prevents drugs in the bloodstream from getting inside the brain to treat diseases, such as cancer. "Our research shows that blood vessel cells lacking Frizzled-4 are leaky. With this information in hand, we hope that someday it may be possible to temporarily loosen the blood-brain barrier, allowing life-saving drugs to pass through," says Nathans.

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the paper are Yanshu Wang, Amir Rattner, Yulian Zhou, John Williams and Philip Smallwood, all from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

This work was supported by grants from the National Eye Institute, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Johns Hopkins Brain Science Institute, the Foundation Fighting Blindness, and the Ellison Medical Foundation.

On the Web:

Nathans Lab: http://neuroscience.jhu.edu/JeremyNathans.php

Media Relations and Public Affairs

Media Contacts: Catherine Kolf; 443-287-2251; ckolf@jhmi.edu

Vanessa McMains; 410-502-9410; vmcmain1@jhmi.edu

Shawna Williams; 410-955-8236; shawna@jhmi.edu

Research on blood vessel proteins holds promise for controlling 'blood-brain barrier'

Experiments also suggest approaches to treating blood vessel disorders in the eye

2012-12-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Immune system kill switch could be target for chemotherapy and infection recovery

2012-12-06

Researchers have discovered an immune system 'kill switch' that destroys blood stem cells when the body is under severe stress, such as that induced by chemotherapy and systemic infections.

The discovery could have implications for protecting the blood system during chemotherapy or in diseases associated with overwhelming infection, such as sepsis.

The kill switch is triggered when internal immune cell signals that protect the body from infection go haywire. Dr Seth Masters, Dr Motti Gerlic, Dr Benjamin Kile and Dr Ben Croker from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute ...

Nobody's perfect

2012-12-06

Researchers at Cambridge and Cardiff have found that, on average, a normal healthy person carries approximately 400 potentially damaging DNA variants and two variants known to be associated directly with disease traits. They showed that one in ten people studied is expected to develop a genetic disease as a consequence of carrying these variants.

It has been known for decades that all people carry some damaging genetic variants that appear to cause little or no ill effect. But this is the first time that researchers have been able to quantify how many such variants each ...

Overestimation of abortion deaths in Mexico hinders maternal mortality reduction efforts

2012-12-06

This press release is available in Spanish and Portuguese.

A collaborative study conducted in Mexico by researchers of the University of West Virginia-Charleston (USA), Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla (Mexico), Universidad de Chile and the Institute of Molecular Epidemiology of the Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción (Chile), revealed that IPAS-Mexico overestimated rates of maternal and abortion mortality up to 35% over the last two decades. The research, recently published in the International Journal of Women's Health highlights that Mexico ...

Researchers discover regulator linking exercise to bigger, stronger muscles

2012-12-06

BOSTON - Scientists at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute have isolated a previously unknown protein in muscles that spurs their growth and increased power following resistance exercise. They suggest that artificially raising the protein's levels might someday help prevent muscle loss caused by cancer, prolonged inactivity in hospital patients, and aging.

Mice given extra doses of the protein gained muscle mass and strength, and rodents with cancer were much less affected by cachexia, the loss of muscle that often occurs in cancer patients, according to the report in the Dec. ...

A relationship between cancer genes and the reprogramming gene SOX2 discovered

2012-12-06

A team of researchers from the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), led by Manuel Serrano, from the Tumour Suppression Group, together with scientists from London and Santiago de Compostela, has discovered that the cellular reprogramming gene SOX2, which is involved in several types of cancers, such as lung cancer and pituitary cancer, is directly regulated by the tumor suppressor CDKN1B(p27) gene, which is also associated with these types of cancer.

The same edition of the online version of the journal also includes a study led by Massimo Squatrito, who recently ...

Study IDs gene that turns carbs into fat

2012-12-06

Berkeley — A gene that helps the body convert that big plate of holiday cookies you just polished off into fat could provide a new target for potential treatments for fatty liver disease, diabetes and obesity.

Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, are unlocking the molecular mechanisms of how our body converts dietary carbohydrates into fat, and as part of that research, they found that a gene with the catchy name BAF60c contributes to fatty liver, or steatosis.

In the study, to be published online Dec. 6 in the journal Molecular Cell, the researchers ...

ACNP: Novel NMDA receptor modulator significantly reduces depression scores within hours

2012-12-06

HOLLYWOOD, FL and EVANSTON, IL, December 6, 2012 -- Naurex Inc., a clinical stage company developing innovative treatments to address unmet needs in psychiatry and neurology, today reported positive results from a Phase IIa clinical trial of its lead antidepressant compound, GLYX-13. GLYX-13 is a novel partial agonist of the NMDA receptor. The Phase Ila results are being presented this week at the 51st Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP).

The Phase IIa results show that a single administration of GLYX-13 produced statistically significant ...

Research yields understanding of Darwin's 'abominable mystery'

2012-12-06

Research by Indiana University paleobotanist David L. Dilcher and colleagues in Europe sheds new light on what Charles Darwin famously called "an abominable mystery": the apparently sudden appearance and rapid spread of flowering plants in the fossil record.

Writing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers present a scenario in which flowering plants, or angiosperms, evolved and colonized various types of aquatic environments over about 45 million years in the early to middle Cretaceous Period.

Dilcher is professor emeritus at IU Bloomington ...

Environmental chemical blocks cell function

2012-12-06

Bisphenol A, a substance found in many synthetic products, is considered to be harmful, particularly, for fetuses and babies. Researchers from the University of Bonn have now shown in experiments on cells from human and mouse tissue that this environmental chemical blocks calcium channels in cell membranes. Similar effects are elicited by drugs used to treat high blood pressure and cardiac arrhythmia. The results are now presented in the journal "Molecular Pharmacology."

The industrial chemical bisphenol A (BPA) is worldwide extensively utilized for manufacturing polycarbonates ...

New evidence for epigenetic effects of diet on healthy aging

2012-12-06

New research in human volunteers has shown that molecular changes to our genes, known as epigenetic marks, are driven mainly by ageing but are also affected by what we eat.

The study showed that whilst age had the biggest effects on these molecular changes, selenium and vitamin D status reduced the accumulation of epigenetic changes, and high blood folate and obesity increased them. These findings support the idea that healthy ageing is affected by what we eat.

Researchers from the Institute of Food Research led by Dr Nigel Belshaw, working with Prof John Mathers and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ACES marks 150 years of the Morrow Plots, our nation's oldest research field

Physicists open door to future, hyper-efficient ‘orbitronic’ devices

$80 million supports research into exceptional longevity

Why the planet doesn’t dry out together: scientists solve a global climate puzzle

Global greening: The Earth’s green wave is shifting

You don't need to be very altruistic to stop an epidemic

Signs on Stone Age objects: Precursor to written language dates back 40,000 years

MIT study reveals climatic fingerprints of wildfires and volcanic eruptions

A shift from the sandlot to the travel team for youth sports

Hair-width LEDs could replace lasers

The hidden infections that refuse to go away: how household practices can stop deadly diseases

Ochsner MD Anderson uses groundbreaking TIL therapy to treat advanced melanoma in adults

A heatshield for ‘never-wet’ surfaces: Rice engineering team repels even near-boiling water with low-cost, scalable coating

Skills from being a birder may change—and benefit—your brain

Waterloo researchers turning plastic waste into vinegar

Measuring the expansion of the universe with cosmic fireworks

How horses whinny: Whistling while singing

US newborn hepatitis B virus vaccination rates

When influencers raise a glass, young viewers want to join them

Exposure to alcohol-related social media content and desire to drink among young adults

Access to dialysis facilities in socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged communities

Dietary patterns and indicators of cognitive function

New study shows dry powder inhalers can improve patient outcomes and lower environmental impact

Plant hormone therapy could improve global food security

A new Johns Hopkins Medicine study finds sex and menopause-based differences in presentation of early Lyme disease

Students run ‘bee hotels’ across Canada - DNA reveals who’s checking in

SwRI grows capacity to support manufacture of antidotes to combat nerve agent, pesticide exposure in the U.S.

University of Miami business technology department ranked No. 1 in the nation for research productivity

Researchers build ultra-efficient optical sensors shrinking light to a chip

Why laws named after tragedies win public support

[Press-News.org] Research on blood vessel proteins holds promise for controlling 'blood-brain barrier'Experiments also suggest approaches to treating blood vessel disorders in the eye