(Press-News.org) Galveston, Texas — Stillbirth is a tragedy that occurs in one of every 160 births in the United States. Compounding the sadness for many families, the standard medical test used to examine fetal chromosomes often can't pin down what caused their baby to die in utero. In most cases, the cause of the stillbirth is not immediately known. The traditional way to determine what happened is to examine the baby's chromosomes using a technique called karyotyping. This method leaves much to be desired because, in many cases, it fails to provide any result at all. Today, some 25 to 60 percent of stillbirths are still unexplained.

A new test for analyzing the chromosomes of stillborn babies, known as microarray analysis, has now proven 40 percent more effective in pinpointing potential genetic causes of death than the old karyotype testing procedure. Researchers at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, along with a team of other national leaders in maternal-fetal medicine, have published their findings in the Dec. 6 New England Journal of Medicine.

"Families have a much greater sense of closure if they understand what likely caused their baby to die," said Dr. George Saade, lead investigator of the UTMB arm of the study. "And for doctors to be able to see more genetic information about each stillborn baby can only be a good thing in terms of continuing the fight to reduce stillbirths worldwide."

Stillbirth, as defined separately from miscarriage, is when a baby dies in the womb prior to delivery at or after 20 weeks of gestation.

The study, part of the National Institutes of Health Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network's ongoing program, showed that microarray analysis genetic testing offers families strikingly more information than karyotyping about what potentially caused their baby to die before it was born. UTMB's Saade is the lead investigator for the study at UTMB, and chairman of the genetics committee for the Stillbirth Network.

The researchers compared the results of karyotypes from more than 500 stillbirths to results from microarray analysis, a method that detects small segments of missing parts of chromosomes (deletions) or additional sections of genetic material (duplications) that cannot be seen by karyotyping.

They analyzed samples from all stillbirths in a population-based study in five U.S. areas, covered by 59 hospitals over a period of two and a half years. Shortly after each stillbirth, parents gave research staff permission to collect blood from the umbilical cord and tissue from the fetus and the placenta.

The UTMB research team's goal was to reach the parents of 90 percent of all stillborn babies to residents of Galveston and Brazoria counties during the time period of the study. To achieve this, they formed partnerships with 11 hospitals in the region and developed a methodology whereby stillbirths were reported immediately to UTMB if the stillborn child's parents granted permission. Upon notification, UTMB sent staff members to the hospital to meet with the bereaved families.

If the families agreed to take part in the study, UTMB staff members then worked with the participating hospitals to transport the babies to Galveston for genetic testing and/or autopsy before arranging with funeral homes for the babies' final transport. About 100 stillbirths occurred in the Galveston/Brazoria county region during the two and a half years the study took place.

"It's really something, that families in such a tough situation, with all the shock and sadness they must be feeling upon the loss of their baby, would be willing to work with us to conduct this important stillbirth research," said Saade.

The hospitals included in the UTMB arm of the study were Angleton Danbury Medical Center, Brazosport Memorial Hospital, Clear Lake Regional Medical Center, Memorial Hermann Hospital, Mainland Medical Center, Methodist Hospital, Memorial Hermann Southeast Hospital, Christus St. John Hospital, St. Joseph Medical Center, St. Luke's Episcopal Hospital, the Woman's Hospital of Texas and UTMB.

"We are so glad that the data from our region was included in this important national study," said Saade. "We are proud here at UTMB that our national reputation as a leader in maternal-fetal clinical research has enabled us to be part of this Network and study, and that we were able to work with such an outstanding group of participating hospitals."

###

Saade and colleague Dr. Radek Bukowski are UTMB's named authors on the paper.

Dr. Uma Reddy, of the Pregnancy and Perinatology Branch of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, the NIH institute leading the research, is the study's first author. The Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network is supported by the NICHD.

Reddy collaborated with 17 co-authors from the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network, all selected for participation because they are recognized as the top national leaders in maternal-fetal clinical research. Besides UTMB the institutions represented in the collaborative study include RTI International, Research Triangle Park, N.C.; University of Utah and Intermountain Health Care, Salt Lake City; Brown University, Providence, R.I.; Emory University and Children's Health Care of Atlanta; University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio; and Columbia University Medical Center, New York City.

The University of Texas Medical Branch

Office of Public Affairs

301 University Boulevard, Suite 3.102

Galveston, Texas 77555-0144

www.utmb.edu

ABOUT UTMB HEALTH: Established in 1891, Texas' first academic health center comprises four health sciences schools, three institutes for advanced study, a research enterprise that includes one of only two national laboratories dedicated to the safe study of infectious threats to human health, and a health system offering a full range of primary and specialized medical services throughout Galveston County and the Texas Gulf Coast region. UTMB Health is a component of the University of Texas System and a member of the Texas Medical Center.

Unlocking the genetic mysteries behind stillbirth

2012-12-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Different genes behind same adaptation to thin air

2012-12-07

Highlanders in Tibet and Ethiopia share a biological adaptation that enables them to thrive in the low oxygen of high altitudes, but the ability to pass on the trait appears to be linked to different genes in the two groups, research from a Case Western Reserve University scientist and colleagues shows.

The adaptation is the ability to maintain a relatively low (for high altitudes) level of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells. Members of ethnic populations - such as most Americans - who historically live at low altitudes naturally respond to the ...

Deception can be perfected

2012-12-07

EVANSTON, Ill. --- With a little practice, one could learn to tell a lie that may be indistinguishable from the truth.

New Northwestern University research shows that lying is more malleable than previously thought, and with a certain amount of training and instruction, the art of deception can be perfected.

People generally take longer and make more mistakes when telling lies than telling the truth, because they are holding two conflicting answers in mind and suppressing the honest response, previous research has shown. Consequently, researchers in the present study ...

Gladstone scientists discover novel mechanism by which calorie restriction influences longevity

2012-12-07

SAN FRANCISCO, CA—December 6, 2012—Scientists at the Gladstone Institutes have identified a novel mechanism by which a type of low-carb, low-calorie diet—called a "ketogenic diet"—could delay the effects of aging. This fundamental discovery reveals how such a diet could slow the aging process and may one day allow scientists to better treat or prevent age-related diseases, including heart disease, Alzheimer's disease and many forms of cancer.

As the aging population continues to grow, age-related illnesses have become increasingly common. Already in the United States, ...

Attitudes predict ability to follow post-treatment advice

2012-12-07

SAN ANTONIO, TX (December 6, 2012)—Women are more likely to follow experts' advice on how to reduce their risk of an important side effect of breast cancer surgery—like lymphedema—if they feel confident in their abilities and know how to manage stress, according to new research from Fox Chase Cancer Center to be presented at the 2012 CTRC-AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium on Saturday, December 8, 2012.

These findings suggest that clinicians must do more than just inform women of the ways they should change their behavior, says Suzanne M. Miller, PhD, Professor ...

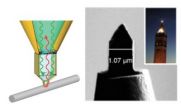

Seeing in color at the nanoscale

2012-12-07

If nanoscience were television, we'd be in the 1950s. Although scientists can make and manipulate nanoscale objects with increasingly awesome control, they are limited to black-and-white imagery for examining those objects. Information about nanoscale chemistry and interactions with light—the atomic-microscopy equivalent to color—is tantalizingly out of reach to all but the most persistent researchers.

But that may all change with the introduction of a new microscopy tool from researchers at the Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley ...

Notre Dame research reveals migrating Great Lakes salmon carry contaminants upstream

2012-12-07

Be careful what you eat, says University of Notre Dame stream ecologist Gary Lamberti.

If you're catching and eating fish from a Lake Michigan tributary with a strong salmon run, the stream fish — brook trout, brown trout, panfish — may be contaminated by pollutants carried in by the salmon.

Research by Lamberti, professor and chair of biology, and his laboratory has revealed that salmon, as they travel upstream to spawn and die, carry industrial pollutants into Great Lakes streams and tributaries. The research was recently published in the journal Environmental Science ...

Silver nanocubes make super light absorbers

2012-12-07

DURHAM, N.C. -- Microscopic metallic cubes could unleash the enormous potential of metamaterials to absorb light, leading to more efficient and cost-effective large-area absorbers for sensors or solar cells, Duke University researchers have found.

Metamaterials are man-made materials that have properties often absent in natural materials. They are constructed to provide exquisite control over the properties of waves, such as light. Creating these materials for visible light is still a technological challenge that has traditionally been achieved by lithography, in which ...

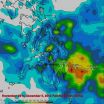

NASA compiles Typhoon Bopha's Philippines Rainfall totals from space

2012-12-07

NASA's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission, or TRMM satellite can estimate rainfall rates from its orbit in space, and its data is also used to compile estimated rainfall totals. NASA just released an image showing those rainfall totals over the Philippines, where severe flooding killed several hundred people. Bopha is now a tropical storm in the South China Sea.

High winds, flooding and landslides from heavy rains with Typhoon Bopha have caused close to 300 deaths in the southern Philippines.

The TRMM satellite's primary mission is the measurement of rainfall in the ...

UC Davis study shows that treadmill testing can predict heart disease in women

2012-12-07

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) — Although there is a widespread belief among physicians that the exercise treadmill test (ETT) is not reliable in evaluating the heart health of women, UC Davis researchers have found that the test can accurately predict coronary artery disease in women over the age of 65. They also found that two specific electrocardiogram (EKG) indicators of heart stress during an ETT further enhanced its predictive power.

Published in the December issue of The American Journal of Cardiology, the study can help guide cardiologists in making the treadmill test ...

TGen-US Oncology data guides treatment of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer patients

2012-12-07

PHOENIX, Ariz. — Dec. 6, 2012 — Genomic sequencing has revealed therapeutic drug targets for difficult-to-treat, metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), according to an unprecedented study by the Translational Genomic Research Institute (TGen) and US Oncology Research.

The study is published by the journal Molecular Cancer Therapeutics and is currently available online.

By sequencing, or spelling out, the billions of letters contained in the genomes of 14 tumors from ethnically diverse metastatic TNBC patients, TGen and US Oncology Research investigators found ...