(Press-News.org) Because of the process involved in the formation of sperm cells, there should be an equal chance that a mammalian egg will be fertilized by "male" sperm, carrying a Y chromosome, as by a "female" sperm, carrying an X chromosome. The symmetry of the system ensures that roughly the same number of males and females are born, which is clearly helpful for the species' long-term survival.

Surprisingly, though, many mammals do not produce equal numbers of male and female offspring. The discrepancy could theoretically be explained by differential fertilization efficiencies of male and female sperm (Y chromosomes are smaller than X chromosomes so perhaps male sperm can swim faster?) or by different rates of survival of male and female foetuses in the uterus. Indeed, it does seem as though male embryos are better able to survive under conditions of high energy intake. But how does this work?

Jana Beckelmann in Christine Aurich's laboratory at the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna now presents provocative evidence that a particular protein, insulin-like growth factor-1 or IGF1, might somehow be involved. From an examination of about 30 embryos, Beckelmann noticed that during early pregnancy (between eight and twelve days after fertilization) the level of messenger RNA encoding IGF1 was approximately twice as high in female embryos as in male embryos.

The difference could relate to the fact that female embryos have two X chromosomes, which might produce more of a factor required for the expression of the IGF1 gene (which is not encoded on the X chromosome) than the single X chromosome in males is able to generate. Beckelmann was also able to confirm that the IGF1 protein was present in the embryos, confirming that the messenger RNA is actually translated to protein.

IGF1 is known to have important functions in growth and to inhibit apoptosis, or programmed cell death. As IGF1 treatment of cattle embryos produced in vivo improves their survival, it is likely that the factor has positive effects on the development of the early embryo in the horse. So why should female embryos contain more of the factor than males?

Losses in early pregnancy are unusually high in the horse and it is believed that female embryos are especially prone to spontaneous abortion. Male embryos are known to be better able to survive under high glucose concentrations, so well-nourished mares preferentially give birth to male foals.

As Beckelmann says, "We think the higher IGF1 concentrations in female embryos might represent a mechanism to ensure the survival of the embryos under conditions that would otherwise strongly favour males." If this is so, the ratio of the sexes in horses is the result of a subtle interplay between environmental and internal factors, including insulin-like growth factor-1.

### The paper "Sex-dependent insulin like growth factor-1 expression in preattachment equine embryos" by Jana Beckelmann, Sven Budik, Magdalena Helmreich, Franziska Palm, Ingrid Walter and Christine Aurich is published online in the journal "Theriogenology" and will be published in print in the journal's January 1, 2013 issue (Volume 79, Issue 1, 1 January 2013, pp. 193-199).

Abstract of the scientific article online (full text for a fee or with a subscription):

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2012.10.004

About the Vienna University of Veterinary Medicine

The University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna is the only academic and research institution in Austria that focuses on the veterinary sciences. About 1000 employees and 2300 students work on the campus in the north of Vienna, which also houses the animal hospital and various spin-off-companies.

http://www.vetmeduni.ac.at

Scientific contact:

Prof. Christine Aurich

Equine Clinic

University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna

christine.aurich@vetmeduni.ac.at

T +43 664-60257-6400

Distributed by:

Klaus Wassermann

Public Relations/Science Communication

University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna

klaus.wassermann@vetmeduni.ac.at

T +43 1 25077-1153

Survival of the females

2012-12-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

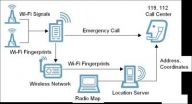

KAIST announces a major breakthrough in high-precision indoor positioning

2012-12-18

Daejeon, Republic of Korea, December 18th, 2012—Cell phones are becoming ever smarter, savvy enough to tell police officers where to go to find a missing person or recommend a rescue team where they should search for survivors when fire erupts in tall buildings. Although still in its nascent stages, indoor positioning system will soon be an available feature on mobile phones.

People widely rely on the Global Positioning System (GPS) for location information, but GPS does not work well in indoor spaces or urban canyons with streets cutting through dense blocks of high-rise ...

Silent stroke can cause Parkinson's disease

2012-12-18

Scientists at The University of Manchester have for the first time identified why a patient who appears outwardly healthy may develop Parkinson's disease.

Whilst conditions such as a severe stroke have been linked to the disease, for many sufferers the tremors and other symptoms of Parkinson's disease can appear to come out of the blue. Researchers at the university's Faculty of Life Sciences have now discovered that a small stroke, also known as a silent stroke, can cause Parkinson's disease. Their findings have been published in the journal "Brain Behaviour and Immunity".

Unlike ...

Prehistoric ghosts revealing new details

2012-12-18

Scientists at The University of Manchester have used synchrotron-based imaging techniques to identify previously unseen anatomy preserved in fossils.

Their work on a 50 million year old lizard skin identified the presence of teeth (invisible to visible light), demonstrating for the first time that this fossil animal was more than just a skin moult. This was only possible using some of the brightest light in the universe, x-rays generated by a synchrotron.

Dr Phil Manning, Dr Nick Edwards, Dr Roy Wogelius and colleagues from the Palaeontology Research group used Synchrotron ...

Research finds crisis in Syria has Mesopotamian precedent

2012-12-18

Research carried out at the University of Sheffield has revealed intriguing parallels between modern day and Bronze-Age Syria as the Mesopotamian region underwent urban decline, government collapse, and drought.

Dr Ellery Frahm from the University of Sheffield's Department of Archaeology made the discoveries by studying stone tools of obsidian, razor-sharp volcanic glass, crafted in the region about 4,200 years ago.

Dr Frahm used artefacts unearthed from the archaeological site of Tell Mozan, known as Urkesh in antiquity, to trace what happened to trade and social networks ...

pH measurements: How to see the real face of electrochemistry and corrosion?

2012-12-18

For several decades antimony electrodes have been used to measure the acidity/basicity – and so to determine the pH value. Unfortunately, they allow for measuring pH changes of solutions only at a certain distance from electrodes or corroding metals. Researchers at the Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences developed a method for producing antimony microelectrodes that allow for measuring pH changes just over the metal surface, at which chemical reactions take place.

Changes in solution acidity/basicity provide important information on the nature ...

Patients with diabetes may not receive best treatment to lower heart disease risk

2012-12-18

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — For some people with diabetes, there may be such a thing as too much care.

Traditional treatment to reduce risks of heart disease among patients with diabetes has focused on lowering all patients' blood cholesterol to a specific, standard level. But this practice may prompt the over-use of high-dose medications for patients who don't need them, according to new research from the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) and the University of Michigan Health System.

The study encourages a more individualized approach to treatment that adjusts treatment ...

Way to make one-way flu vaccine discovered by Georgia State researcher

2012-12-18

A new process to make a one-time, universal influenza vaccine has been discovered by a researcher at Georgia State University's Center for Inflammation, Immunity and Infection and his partners.

Associate Professor Sang-Moo Kang and his collaborators have found a way to make the one-time vaccine by using recombinant genetic engineering technology that does not use a seasonal virus.

Instead, the new vaccine uses a virus' small fragment that does not vary among the different strains of flu viruses.

By using the fragment and generating particles mimicking a virus in ...

Southampton researchers find a glitch' in pulsar 'glitch' theory

2012-12-18

Researchers from the University of Southampton have called in to question a 40 year-old theory explaining the periodic speeding up or 'glitching' of pulsars.

A pulsar is a highly magnetised rotating neutron star formed from the remains of a supernova. It emits a rotating beam of electromagnetic radiation, which can be detected by powerful telescopes when it sweeps past the Earth, rather like observing the beam of a lighthouse from a ship at sea.

Pulsars rotate at extremely stable speeds, but occasionally they speed up in brief events described as 'glitches' or 'spin-ups'. ...

Women earn more if they work in different occupations than men

2012-12-18

Women earn less money than men the more the sexes share the same occupations, a large-scale survey of 20 industrialised countries has found.

Researchers from the universities of Cambridge, UK, and Lakehead, Canada, found that the more women and men keep to different trades and professions, the more equal is the overall pay average for the two sexes in a country.

The researchers attribute the surprising results to the fact that when there are few men in an occupation, women have more chance to get to the top and earn more. But where there are more equal numbers of ...

Visions of snowflakes: An American Chemical Society holiday video

2012-12-18

WASHINGTON, Dec. 18, 2012 — For everyone with holiday visions of snowflakes dancing in their heads, the American Chemical Society, the world's largest scientific society, today issued a video explaining how dust, water, cold and air currents collaborate to form these symbols of the season. It's all there in an episode of Bytesize Science, the award-winning video series produced by the ACS Office of Public Affairs at www.BytesizeScience.com.

The video tracks formation of snowflakes from their origins in bits of dust in clouds that become droplets of water falling to Earth. ...