(Press-News.org) CHAPEL HILL - Long-standing research efforts have been focused on understanding how stem cells, cells capable of transforming into any type of cell in the body, are capable of being programmed down a defined path to contribute to the development of a specific organ like a heart, lung, or kidney. Research from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine has shed new light on how epigenetic signals may function together to determine the ultimate fate of a stem cell.

The study, published December 27, 2012 by the journal Molecular Cell, implicates a unique class of proteins called polycomb-like proteins, or PCL's, as bridging molecules between the "on" and "off" state of a gene. While all of these specialized types of cells share the same genetic information encoded in our DNA, it is becoming increasingly clear that information outside the genome, referred to as epigenetics, plays a central role in orchestrating the reprogramming of a stem cell down a defined path.

Although it is understood that epigenetics is responsible for turning genes "on" and "off" at defined times during cellular development, the precise mechanisms controlling this delicate process are less well understood.

"This finding has important implications for both stem cell biology and cancer development, as the same regulatory circuits controlled by PCL's in stem cells are often misregulated in tumors," said Dr. Greg Wang, senior author of the study and Assistant Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics in the UNC School of Medicine and a member of UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

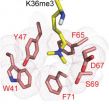

The study, led by postdoctoral research fellows Drs. Ling Cai and Rui Lu in the Wang lab, and Dr. Scott Rothbart, a Lineberger postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Dr. Brian Strahl, Associate Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics in the UNC School of Medicine and a member of UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, identified that PCL's interact with an epigenetic signal associated with genes that are turned on to recruit a group of proteins called the PRC2 complex which then turn genes off.

"In stem cells, the PRC2 complex turns genes off that would otherwise promote reprogramming into specialized cells of organs like the heart or lungs," said Wang.

In addition to its fundamental role in cellular development, elevated levels of PRC2 have been found in cancers of the prostate, breast, lung, and blood, and pharmaceutical companies are already developing drugs to target PRC2. Wang and colleagues determined that the same mechanisms controlling PRC2 function in stem cells also applies in human cancers.

"The identification of a specific PCL in controlling PRC2 in cancer cells suggests we may be able to develop drugs targeting this PCL to regulate PRC2 function in a more controlled manner that may maintain PRC2 function in stem cells while inhibiting it in the tumor," said Wang.

INFORMATION:

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health grants (GM085394 and GM068088), the Department of Defense, the V Foundation for Cancer Research, and the University Cancer Research Fund, and was performed in collaboration with scientists at the University of California at Riverside, Rockefeller University, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Study co-authors from UNC also included Bowen Xu, a student in the Wang Lab, and Ashutosh Tripathy, a Research Professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics.

UNC research uncovers new insight into cell development and cancer

2012-12-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Genetic sequencing breakthrough to aid treatment for congenital hyperinsulinism

2012-12-27

Congenital hyperinsulinism is a genetic condition where a baby's pancreas secretes too much insulin. It affects approximately one in 50,000 live births and in severe cases requires the surgical removal of all or part of the pancreas.

Researchers at the University of Exeter Medical School are the first in the world to utilise new genetic sequencing technology to sequence the entirety of a gene in order to identify mutations that cause hyperinsulinism. Previously, existing technology limited such sequencing to only part of the coding regions of the gene which meant that ...

Cellular fuel gauge may hold the key to restricting cancer growth

2012-12-27

Researchers at McGill University have discovered that a key regulator of energy metabolism in cancer cells known as the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) may play a crucial role in restricting cancer cell growth. AMPK acts as a "fuel gauge" in cells; AMPK is turned on when it senses changes in energy levels, and helps to change metabolism when energy levels are low, such as during exercise or when fasting. The researchers found that AMPK also regulates cancer cell metabolism and can restrict cancer cell growth.

The discovery was made by Russell (Rusty) Jones, an assistant ...

Stowers study hints that stem cells prepare for maturity much earlier than anticipated

2012-12-27

KANSAS CITY, MO—Unlike less versatile muscle or nerve cells, embryonic stem cells are by definition equipped to assume any cellular role. Scientists call this flexibility "pluripotency," meaning that as an organism develops, stem cells must be ready at a moment's notice to activate highly diverse gene expression programs used to turn them into blood, brain, or kidney cells.

Scientists from the lab of Stowers Investigator Ali Shilatifard, Ph.D., report in the December 27, 2012 online issue of Cell that one way cells stay so plastic is by stationing a protein called Ell3 ...

Evidence contradicts idea that starvation caused saber-tooth cat extinction

2012-12-27

In the period just before they went extinct, the American lions and saber-toothed cats that roamed North America in the late Pleistocene were living well off the fat of the land.

That is the conclusion of the latest study of the microscopic wear patterns on the teeth of these great cats recovered from the La Brea tar pits in southern California. Contrary to previous studies, the analysis did not find any indications that the giant carnivores were having increased trouble finding prey in the period before they went extinct 12,000 years ago.

The results, published on ...

MRI can screen patients for Alzheimer's disease or frontotemporal lobar degeneration

2012-12-27

PHILADELPHIA - When trying to determine the root cause of a person's dementia, using an MRI can effectively and non-invasively screen patients for Alzheimer's disease or Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (FTLD), according to a new study by researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Using an MRI-based algorithm effectively differentiated cases 75 percent of the time, according to the study, published in the December 26th, 2012, issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology. The non-invasive approach ...

Drug shortage linked to greater risk of relapse in young Hodgkin lymphoma patients

2012-12-27

A national drug shortage has been linked to a higher rate of relapse among children, teenagers and young adults with Hodgkin lymphoma enrolled in a national clinical trial, according to research led by St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.

Estimated two-year cancer-free survival for patients enrolled in the study fell from 88 to 75 percent after the drug cyclophosphamide was substituted for mechlorethamine for treatment of patients with intermediate- or high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma. The study was launched before the drug shortages began. The change occurred after a mechlorethamine ...

Drug shortage linked to greater risk of relapse in young Hodgkin lymphoma patients

2012-12-27

STANFORD, Calif. — A national drug shortage has been linked to a higher rate of relapse among children, teenagers and young adults with Hodgkin lymphoma enrolled in a national clinical trial, according to research led by St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.

Estimated two-year cancer-free survival for patients enrolled in the study fell from 88 to 75 percent after the drug cyclophosphamide was substituted for mechlorethamine for treatment of patients with intermediate- or high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma. The study was launched before the drug shortages began. The change occurred ...

Kindness key to happiness and acceptance for children

2012-12-27

Children who make an effort to perform acts of kindness are happier and experience greater acceptance from their peers, suggests new research from the University of British Columbia and the University of California, Riverside.

Kimberly Schonert-Reichl, a professor in UBC's Faculty of Education, and co-author Kristin Layous, of the University of California, Riverside, say that increasing peer acceptance is key to preventing bullying.

In the study, published today by PLOS ONE, researchers examined how to boost happiness in students aged 9 to 11 years. Four hundred students ...

For pre-teens, kindness may be key to popularity

2012-12-27

Nine to twelve-year-olds who perform kind acts are not only happier, but also find greater acceptance in their peer groups, according to research published December 26, 2012 in the open access journal PLOS ONE by Kristin Layous and colleagues from the University of California, Riverside.

The authors randomly assigned over 400 students aged 9-12 to two groups: one group performed 'acts of kindness' and the other kept track of pleasant places they visited each week. Examples of kind acts included descriptions like "gave someone some of my lunch" or "gave my mom a hug when ...

Saber-toothed cats in California were not driven to extinction by lack of food

2012-12-27

When prey is scarce, large carnivores may gnaw prey to the bone, wearing their teeth down in the process. A new analysis of the teeth of saber-toothed cats and American lions reveals that they did not resort to this behavior just before extinction, suggesting that lack of prey was probably not the main reason these large cats became extinct. The results, published December 26 in the open access journal PLOS ONE by Larisa DeSantis of Vanderbilt University and colleagues, compares tooth wear patterns from the fossil cats that roamed California 12,000 to 30,000 years ago. ...