Researchers identify new target for common heart condition

Irregular heartbeat affects 750,000 people in the UK

2013-01-08

(Press-News.org) Researchers have found new evidence that metabolic stress can increase the onset of atrial arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation (AF), a common heart condition that causes an irregular and often abnormally fast heart rate. The findings may pave the way for the development of new therapies for the condition which can be expected to affect almost one in four of the UK population at some point in their lifetime.

The British Heart Foundation (BHF) study, led by University of Bristol scientists and published in Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, found that metabolic stress — a condition induced by insufficient oxygen supply to the heart (e.g. following blockage of a coronary artery) — caused marked changes in the electrical activity of the heart's atria (the upper chambers of the heart).

While it has been recognised for many years that metabolic stress causes ventricular arrhythmias — abnormal heart rhythms that originate in the two lower chambers of the heart (the ventricles) and which form the basis to heart attacks — it is the first time it has been demonstrated for arrhythmias in the atria.

The research team led by Dr Andrew James from the University's School of Physiology and Pharmacology together with Professor Saadeh Suleiman in the School of Clinical Sciences, examined the contribution of a particular kind of protein underlying the electrical activity of the atria during metabolic stress.

These proteins, known as KATP channels enable cells to respond to changes in metabolism. ATP (adenosine triphosphate) is a small molecule that represents the 'energy currency' for cell metabolism and when ATP levels inside cells fall, KATP channels are activated. For example, KATP channels in the pancreas are involved in the regulation of insulin secretion and drugs targeting these channels are used to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Dr Andrew James, the study's lead author, said: "It is well-established that KATP channels in the ventricles of the heart can become activated following metabolic stress caused by blockage of a coronary artery. In principle, their activation could protect the heart muscle cells against metabolic stress-induced damage. On the other hand, the activation of ventricular KATP channels can contribute to disturbances in the electrical activity of the heart known as arrhythmias.

"Arrhythmias in the ventricles can be very dangerous, leading to ventricular fibrillation and death. Atrial arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation (AF), are not usually immediately fatal but they are very common and a major cause of stroke. Notably, KATP channels are also found in the atria but, in contrast to the ventricles, their role in atrial arrhythmias remains unknown."

The findings show that metabolic stress caused marked changes in the electrical activity of the atrium consistent with the activation of KATP channels. Electrical stimulation was applied to try to evoke atrial arrhythmia. It was possible to induce atrial arrhythmia during, but not before, metabolic stress.

Importantly, blockade of KATP channels with drugs used to treat patients with type 2 diabetes (glibenclamide and tolbutamide), completely reversed the effects of metabolic stress on the electrical activity of the atrium and prevented the induction of atrial arrhythmia. The anti-diabetic drugs were without effect in the absence of metabolic stress.

The findings represent a 'proof-of-principle' (the stage at which any new drug must undergo before full-scale clinical trials can begin) that atrial KATP channels can be activated by metabolic stress and facilitate atrial arrhythmias. Thus, atrial KATP channels may represent a target for drugs for the treatment of atrial arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation.

However, Dr James added: "Further studies are required and a key point to address will be whether differences exist between the properties of atrial, ventricular and pancreatic KATP channels that might be exploited to produce an atrial-selective drug. Perhaps these channels might be useful as targets to treat atrial arrhythmias."

Professor Jeremy Pearson, Associate Medical Director at the BHF, commented: "Atrial fibrillation is a very common irregular heart rhythm which greatly increases the risk of stroke. This study brings us closer to understanding how it develops, in particular in people whose hearts are under greater pressure due to the effects of a previous history of heart disease. It's vital that we continue to improve our understanding of this condition so we can find new treatments for patients in the future."

###

The BHF-funded study, entitled 'Activation of Glibenclamide-Sensitive KATP Channels during β-Adrenergically-Induced Metabolic Stress Produces a Substrate for Atrial Tachyarrhythmia' is published online in the journal Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2013-01-08

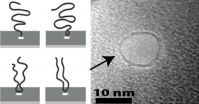

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — If you want to understand a novel, it helps to start from the beginning rather than trying to pick up the plot from somewhere in the middle. The same goes for analyzing a strand of DNA. The best way to make sense of it is to look at it head to tail.

Luckily, according to a new study by physicists at Brown University, DNA molecules have a convenient tendency to cooperate.

The research, published in the journal Physical Review Letters, looks at the dynamics of how DNA molecules are captured by solid-state nanopores, tiny holes that ...

2013-01-08

The nighttime twinkling of fireflies has inspired scientists to modify a light-emitting diode (LED) so it is more than one and a half times as efficient as the original. Researchers from Belgium, France, and Canada studied the internal structure of firefly lanterns, the organs on the bioluminescent insects' abdomens that flash to attract mates. The scientists identified an unexpected pattern of jagged scales that enhanced the lanterns' glow, and applied that knowledge to LED design to create an LED overlayer that mimicked the natural structure. The overlayer, which increased ...

2013-01-08

For over 100 years, it was assumed that the penicillin-producing mould fungus Penicillium chrysogenum only reproduced asexually through spores. An international research team led by Prof. Dr. Ulrich Kück and Julia Böhm from the Chair of General and Molecular Botany at the Ruhr-Universität has now shown for the first time that the fungus also has a sexual cycle, i.e. two "genders". Through sexual reproduction of P. chrysogenum, the researchers generated fungal strains with new biotechnologically relevant properties - such as high penicillin production without the contaminating ...

2013-01-08

Athens, Ga. – On the list of undesirable medical conditions, a parasitic worm infection surely ranks fairly high. Although modern pharmaceuticals have made them less of a threat in some areas, these organisms are still a major cause of disease and disability throughout much of the developing world.

But parasites are not all bad, according to new research by a team of scientists now at the University of Georgia, the Harvard School of Public Health, the Université François Rabelais in Tours, France, and the Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China.

A study ...

2013-01-08

The research carried out at IIASA in collaboration with the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research demonstrates that there is fundamental rigidity, known as lock-in, within the energy economy that favors the use of fossil fuels and nuclear power despite their large environmental and social costs. The researchers identify that this rigidity of the existing energy economy could be considerably reduced by introducing new rules that hold shareholders of companies liable for the damages caused by the companies they own. Allocating the liability between the company and ...

2013-01-08

The flick of an antenna may be how a male wasp lays claim to his harem, according to new research at Simon Fraser University.

A team of biologists, led by former PhD graduate student Kelly Ablard, found that when a male targeted a female, he would approach from her from the left side, and once in range, uses the tip of his antenna to tap her antenna.

Ablard suggests the act transfers a yet unidentified specimen-specific pheromone onto the female's antenna that marks the female as "out of bounds," or "tagged."

The tagging-pheromone helps a male relocate the females ...

2013-01-08

Graphene oxide has a remarkable ability to quickly remove radioactive material from contaminated water, researchers at Rice University and Lomonosov Moscow State University have found.

A collaborative effort by the Rice lab of chemist James Tour and the Moscow lab of chemist Stepan Kalmykov determined that microscopic, atom-thick flakes of graphene oxide bind quickly to natural and human-made radionuclides and condense them into solids. The flakes are soluble in liquids and easily produced in bulk.

The experimental results were reported in the Royal Society of Chemistry ...

2013-01-08

What if Noah got it wrong? What if he paired a male and a female animal thinking they were the same species, and then discovered they were not the same and could not produce offspring? As researchers from the Smithsonian's Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project race to save frogs from a devastating disease by breeding them in captivity, a genetic test averts mating mix-ups.

At the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center, project scientists breed 11 different species of highland frogs threatened by the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, which has already ...

2013-01-08

The American Chemical Society (ACS), the world's largest scientific society, today launched a new video series that will feature noted scientists discussing the status of knowledge in their fields, their own research, and its impacts and potential impacts on society. Chemistry over Coffee: Conversations with Celebrated Scientists is available at www.acs.org/ChemistryOverCoffee.

The launch episode features Chad Mirkin, Ph.D., and Paul Weiss, Ph.D., internationally known leaders in nanotechnology. Mirkin, director of Northwestern University's International Institute for ...

2013-01-08

New research reveals that a significant number of adolescents lose their protection from hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, despite having received a complete vaccination series as infants. Results in the January 2013 issue of Hepatology, a journal published by Wiley on behalf of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, suggest teens with high-risk mothers (those positive for HBeAg) and teens whose immune system fails to remember a previous viral exposure (immunological memory) are behind HBV reinfection.

Infection with HBV is a major global health concern ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Researchers identify new target for common heart condition

Irregular heartbeat affects 750,000 people in the UK