(Press-News.org) Researchers in California and Switzerland have discovered that melanomas that develop resistance to the anti-cancer drug vemurafenib (marketed as Zelboraf), also develop addiction to the drug, an observation that may have important implications for the lives of patients with late-stage disease.

The team, based at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research (NIBR) in Emeryville, Calif., and University Hospital Zurich, found that one mechanism by which melanoma cells become resistant to vemurafenib also renders them "addicted" to the drug. As a result, the melanoma cells nefariously use vemurafenib to spur the growth of rapidly progressing, deadly and drug-resistant tumors.

As described this week in the journal Nature, the team built upon this basic discovery and showed that adjusting the dosing of the drug and introducing an on-again, off-again treatment schedule prolonged the life of mice with melanoma.

"Remarkably, intermittent dosing with vemurafenib prolonged the lives of mice with drug-resistant melanoma tumors," said co-lead researcher Martin McMahon, PhD, the Efim Guzik Distinguished Professor of Cancer Biology in the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

It is therefore possible that a similar approach may extend the effectiveness of the drug for people – an idea that awaits testing in clinical trials.

Investigated through a public-private partnership, the research was spearheaded by the study's first author Meghna Das Thakur, PhD, a Novartis Presidential Postdoctoral Fellow, who was co-mentored by McMahon at UCSF and Darrin Stuart, PhD at NIBR.

McMahon is supported by the Melanoma Research Alliance, the National Cancer Institute and the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, which is one of the country's leading research and clinical care centers, and is the only comprehensive cancer center in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Melanoma: A Deadly Form of Skin Cancer

Melanoma is the most aggressive type of skin cancer, and in 2012 alone, an estimated 76,250 people in the United States were newly diagnosed with it. Some 9,180 people died last year from the disease, according to the National Cancer Institute.

As with all forms of cancer, melanoma starts with normal cells in the body that accumulate mutations and undergo transformations that cause them to grow aberrantly and metastasize. One of the most common mutations in melanoma occurs in a gene called BRAF, and more than half of all people with melanoma express mutated BRAF.

In 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the drug vemurafenib for patients who have late-stage melanoma with mutations in BRAF after clinical trials showed a significant increase in survival for such patients when taking the drug. The drug's benefits do not last forever, though, and while their tumors may initially shrink, most people on vemurafenib suffer cancer recurrence in the long run with a lethal, drug-resistant form of melanoma.

In the laboratory, the same phenomenon can be observed in mice. When small melanoma tumor fragments are implanted in mice, the tumors will initially shrink in response to drug, but eventually the mice will cease to respond to the drug and their tumors will re-emerge in a resistant form.

Targeting the Mechanism of Resistance

Working with such laboratory models, the UCSF and NIBR research teams were able to determine the mechanism of resistance. They discovered that when melanoma cells are subjected to vemurafenib, they become resistant by making more of the BRAF protein – the very target of the drug itself.

The idea for intermittent dosing came directly from this insight. If by becoming resistant to vemurafenib's anti-cancer potency, melanoma also becomes addicted to it, Das Thakur and her colleagues reasoned, then drug-resistant tumors may shrink when the vemurafenib is removed. That's exactly what they observed.

The team discovered that when they stopped administering the drug to mice with resurgent, resistant tumors, the tumors once again shrank. In addition, mice continuously treated with vemurafenib all died of drug-resistant disease within about 100 days, whereas all the mice treated with vemurafenib but with regular "drug holidays" all lived past 100 days.

"Vemurafenib has revolutionized treatment of a specific subset of melanoma expressing mutated BRAF, but its long-term effectiveness is diminished by the development of drug resistance," said McMahon, the Efim Guzik Distinguished Professor of Cancer Biology in the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center. "By seeking to understand the mechanisms of drug resistance, we have also found a way to enhance the durability of the drug response via intermittent dosing."

INFORMATION:

The article, "Modeling vemurafenib resistance in melanoma reveals a strategy to forestall drug resistance" is authored by Meghna Das Thakur, Fernando Salangsang, Allison S. Landman, William R. Sellers, Nancy K. Pryer, Mitchell P. Levesque, Reinhard Dummer, Martin McMahon and Darrin Stuart. It appears in the Jan. 9, 2013, issue of the journal Nature. After publication, the article can be accessed at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature11814

UCSF is a leading university dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care.

Follow UCSF

UCSF.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | Twitter.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

Drug-resistant melanoma tumors shrink when therapy is interrupted

'Intermittent dosing' strategy in lab mice suggests simple way to help people with late-stage melanoma

2013-01-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The farthest supernova yet for measuring cosmic history

2013-01-10

What if you had a "Wayback Television Set" and could watch an entire month of ancient prehistory unfold before your eyes in real time? David Rubin of the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) presented just such a scenario to the American Astronomical Society (AAS) meeting in Long Beach, CA, when he announced the discovery of a striking astronomical object: a Type Ia supernova with a redshift of 1.71 that dates back 10 billion years in time. Labeled SN SCP-0401, the supernova is exceptional for its detailed spectrum and precision ...

Spin and bias in published studies of breast cancer trials

2013-01-10

Spin and bias exist in a high proportion of published studies of the outcomes and adverse side-effects of phase III clinical trials of breast cancer treatments, according to new research published in the cancer journal Annals of Oncology [1] today (Thursday).

In the first study to investigate how accurately outcomes and side-effects are reported in breast cancer trials, researchers at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and University of Toronto (Toronto, Canada) found that in a third of all trials that failed to show a statistically significant benefit for the treatment ...

Particles of crystalline quartz wear away teeth

2013-01-10

This press release is available in German.

Dental microwear, the pattern of tiny marks on worn tooth surfaces, is an important basis for understanding the diets of fossil mammals, including those of our own lineage. Now nanoscale research by an international multidisciplinary group that included members of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig has unraveled some of its causes. It turns out that quartz dust is the major culprit in wearing away tooth enamel. Silica phytoliths, particles produced by plants, just rub enamel, and thus have ...

First image of insulin 'docking' could lead to better diabetes treatments

2013-01-10

A landmark discovery about how insulin docks on cells could help in the development of improved types of insulin for treating both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

For the first time, researchers have captured the intricate way in which insulin uses the insulin receptor to bind to the surface of cells. This binding is necessary for the cells to take up sugar from the blood as energy.

The research team was led by the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and used the Australian Synchrotron in Melbourne, Australia. The study was published today in the journal Nature.

For more ...

Magma in mantle has deep impact

2013-01-10

HOUSTON – (Jan. 9, 2013) – Magma forms far deeper than geologists previously thought, according to new research at Rice University.

A group led by geologist Rajdeep Dasgupta put very small samples of peridotite under very large pressures in a Rice laboratory to determine that rock can and does liquify, at least in small amounts, as deep as 250 kilometers in the mantle beneath the ocean floor. He said this explains several puzzles that have bothered scientists.

Dasgupta is lead author of the paper to be published this week in Nature.

The mantle is the planet's middle ...

After decades of research, scientists unlock how insulin interacts with cells

2013-01-10

The discovery of insulin nearly a century ago changed diabetes from a death sentence to a chronic disease.

Today a team that includes researchers from Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine announced a discovery that could lead to dramatic improvements in the lives of people managing diabetes.

After decades of speculation about exactly how insulin interacts with cells, the international group of scientists finally found a definitive answer: in an article published today in the journal Nature, the group describes how insulin binds to the cell to allow the ...

GW researchers find variation in foot strike patterns in predominantly barefoot runners

2013-01-10

WASHINGTON –A recently published paper by two George Washington University researchers shows that the running foot strike patterns vary among habitually barefoot people in Kenya due to speed and other factors such as running habits and the hardness of the ground. These results are counter to the belief that barefoot people prefer one specific style of running.

Kevin Hatala, a Ph.D. student in the Hominid Paleobiology doctoral program at George Washington, is the lead author of the paper that appears in the recent edition of the journal Public Library of Science, or PLOS ...

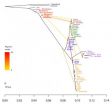

A history lesson from genes

2013-01-10

When Charles Darwin first sketched how species evolved by natural selection, he drew what looked like a tree. The diagram started at a central point with a common ancestor, then the lines spread apart as organisms evolved and separated into distinct species.

In the 175 years since, scientists have come to agree that Darwin's original drawing is a bit simplistic, given that multiple species mix and interbreed in ways he didn't consider possible (though you can't fault the guy for not getting the most important scientific theory of all time exactly right the first time). ...

Study examines how news spreads on Twitter

2013-01-10

Nearly every major news organization has a Twitter account these days, but just how effective is the microblogging website at spreading news? That's the question University of Arizona professor Sudha Ram set out to answer in a recent study of a dozen major news organizations that use the social media website as one tool for sharing their content.

The answer, according to Ram's research, varies widely by news agency, and there may not be one universally applicable strategy for maximizing Twitter effectiveness. However, news agencies can learn a lot by looking at how their ...

Unnecessary antimicrobial use increases risk of recurrent infectious diarrhea

2013-01-10

The impact of antibiotic misuse has far-reaching consequences in healthcare, including reduced efficacy of the drugs, increased prevalence of drug-resistant organisms, and increased risk of deadly infections. A new study featured in the February issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, found that many patients with Clostridium difficile infection (C. difficile) are prescribed unnecessary antibiotics, increasing their risk of recurrence of the deadly infection. The retrospective report shows ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

[Press-News.org] Drug-resistant melanoma tumors shrink when therapy is interrupted'Intermittent dosing' strategy in lab mice suggests simple way to help people with late-stage melanoma