(Press-News.org) The rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria has initiated a quest for alternatives to conventional antibiotics. One potential alternative is PlyC, a potent enzyme that kills the bacteria that causes strep throat and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. PlyC operates by locking onto the surface of a bacteria cell and chewing a hole in the cell wall large enough for the bacteria's inner membrane to protrude from the cell, ultimately causing the cell to burst and die.

Research has shown that alternative antimicrobials such as PlyC can effectively kill bacteria. However, fundamental questions remain about how bacteria respond to the holes that these therapeutics make in their cell wall and what size holes bacteria can withstand before breaking apart. Answering those questions could improve the effectiveness of current antibacterial drugs and initiate the development of new ones.

Researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology and the University of Maryland recently conducted a study to try to answer those questions. The researchers created a biophysical model of the response of a Gram-positive bacterium to the formation of a hole in its cell wall. Then they used experimental measurements to validate the theory, which predicted that a hole in the bacteria cell wall larger than 15 to 24 nanometers in diameter would cause the cell to lyse, or burst. These small holes are approximately one-hundredth the diameter of a typical bacterial cell.

"Our model correctly predicted that the membrane and cell contents of Gram-positive bacteria cells explode out of holes in cell walls that exceed a few dozen nanometers. This critical hole size, validated by experiments, is much larger than the holes Gram-positive bacteria use to transport molecules necessary for their survival, which have been estimated to be less than 7 nanometers in diameter," said Joshua Weitz, an associate professor in the School of Biology at Georgia Tech. Weitz also holds an adjunct appointment in the School of Physics at Georgia Tech.

The study was published online on Jan. 9, 2013 in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface. The work was supported by the James S. McDonnell Foundation and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Common Gram-positive bacteria that infect humans include Streptococcus, which causes strep throat; Staphylococcus, which causes impetigo; and Clostridium, which causes botulism and tetanus. Gram-negative bacteria include Escherichia, which causes urinary tract infections; Vibrio, which causes cholera; and Neisseria, which causes gonorrhea.

Gram-positive bacteria differ from Gram-negative bacteria in the structure of their cell walls. The cell wall constitutes the outer layer of Gram-positive bacteria, whereas the cell wall lies between the inner and outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and is therefore protected from direct exposure to the environment.

Georgia Tech biology graduate student Gabriel Mitchell, Georgia Tech physics professor Kurt Wiesenfeld and Weitz developed a biophysical theory of the response of a Gram-positive bacterium to the formation of a hole in its cell wall. The model detailed the effect of pressure, bending and stretching forces on the changing configuration of the cell membrane due to a hole. The force associated with bending and stretching pulls the membrane inward, while the pressure from the inside of the cell pushes the membrane outward through the hole.

"We found that bending forces act to keep the membrane together and push it back inside, but a sufficiently large hole enables the bending forces to be overpowered by the internal pressure forces and the membrane begins to escape out and the cell contents follow," said Weitz.

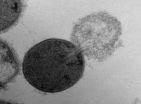

The balance between the bending and pressure forces led to the model prediction that holes 15 to 24 nanometers in diameter or larger would cause a bacteria cell to burst. To test the theory, Daniel Nelson, an assistant professor at the University of Maryland, used transmission electron microscopy images to measure the size of holes created in lysed Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria cells following PlyC exposure.

Nelson found holes in the lysed bacteria cells that ranged in diameter from 22 to 180 nanometers, with a mean diameter of 68 nanometers. These experimental measurements agreed with the researchers' theoretical prediction of critical hole sizes that cause bacterial cell death.

According to the researchers, their theoretical model is the first to consider the effects of cell wall thickness on lysis.

"Because lysis events occur most often at thinner points in the cell wall, cell wall thickness may play a role in suppressing lysis by serving as a buffer against the formation of large holes," said Mitchell.

The combination of theory and experiments used in this study provided insights into the effect of defects on a cell's viability and the mechanisms used by enzymes to disrupt homeostasis and cause bacteria cell death. To further understand the mechanisms behind enzyme-induced lysis, the researchers plan to measure membrane dynamics as a function of hole geometry in the future.

INFORMATION:

CITATION: Mitchell GJ, Wiesenfeld K, Nelson DC, Weitz JS, "Critical cell wall hole size for lysis in Gram-positive bacteria," J R Soc Interface 20120892 (2013): http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2012.0892.

Study quantifies the size of holes antibacterials create in cell walls to kill bacteria

Death on a nanometer scale

2013-01-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study provides new clues for designing an effective HIV vaccine

2013-01-10

New insights into how a promising HIV vaccine works are provided in a study published by Cell Press January 10th in the journal Immunity. By analyzing the structure of antibody-virus complexes produced in vaccine recipients, the researchers have revealed how the vaccine triggers immune responses that could fight HIV-1 infection. The study could help guide efforts to increase the vaccine's production, which currently is not high enough for clinical use.

"This is the first comprehensive study of the repertoire of antibodies that were induced by an HIV vaccine and were ...

Study points to a safer, better test for chromosomal defects in the fetus

2013-01-10

A noninvasive, sequencing-based approach for detecting chromosomal abnormalities in the developing fetus is safer and more informative in some cases than traditional methods, according to a study published by Cell Press January 10th in The American Journal of Human Genetics. This method, which analyzes fetal DNA in the mother's blood, could provide women with a cost-effective way to find out whether their unborn baby will have major developmental problems without risking a miscarriage.

"Our study is the first to show that almost all the information that is available from ...

Regulating single protein prompts fibroblasts to become neurons

2013-01-10

Repression of a single protein in ordinary fibroblasts is sufficient to directly convert the cells – abundantly found in connective tissues – into functional neurons. The findings, which could have far-reaching implications for the development of new treatments for neurodegenerative diseases like Huntington's, Parkinson's and Alzheimer's, will be published online in advance of the January 17 issue of the journal Cell.

In recent years, scientists have dramatically advanced the ability to induce pluripotent stem cells to become almost any type of cell, a major step in ...

Next steps in potential stem cell therapy for diabetes

2013-01-10

Type 1 and type 2 diabetes results when beta cells in the pancreas fail to produce enough insulin, the hormone that regulates blood sugar. One approach to treating diabetes is to stimulate regeneration of new beta cells.

There are currently two ways of generating endocrine cells (cell types, such as beta cells, that secrete hormones) from human embryonic stem cells, or hESCs: either generating the cells in vitro in culture or transplanting immature endocrine cell precursors into mice.

Researchers from the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, collaborating ...

New insights into HIV vaccine will improve drug development

2013-01-10

DURHAM, N.C. – Four years ago, a potential HIV vaccine showed promise against the virus that causes AIDS, but it fell short of providing the broad protection necessary to stem the spread of disease.

Now researchers -- led by Duke Medicine and including team members from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Military HIV Research Program and the Thailand Ministry of Health -- have gained additional insights into the workings of the vaccine that help explain why it benefited a third of recipients and left ...

Cancer scientists determine mechanism of 1 of the most powerful tumor-suppressor proteins, Chd5

2013-01-10

Cold Spring Harbor, NY – A team of cancer researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) has solved the mystery of how one of the most powerful of the body's natural tumor-suppressing proteins, called Chd5, exerts its beneficial effects.

The findings, published online today in the journal Cell Reports, are important because Chd5 engages processes fundamental to cancer prevention. Conversely, when Chd5 is mutated or missing, an important door is opened to cancer initiation.

"For this reason, figuring out the mechanics of how Chd5 works to prevent cancer can directly ...

Researchers find causality in the eye of the beholder

2013-01-10

We rely on our visual system more heavily than previously thought in determining the causality of events. A team of researchers has shown that, in making judgments about causality, we don't always need to use cognitive reasoning. In some cases, our visual brain—the brain areas that process what the eyes sense—can make these judgments rapidly and automatically.

The study appears in the latest issue of the journal Current Biology.

"Our study reveals that causality can be computed at an early level in the visual system," said Martin Rolfs, who conducted much of the research ...

Study identifies infants at highest risk of death from pertussis

2013-01-10

ARLINGTON, VA, January 10, 2013—A study released today from the upcoming issue of the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (JPIDS) found that taking early and repeated white blood cell counts (WBC) is critical in determining whether infants have pertussis and which of those children are at highest risk of death from the disease.

In 2010, California reported its highest pertussis rates in 60 years. Murray, et al.'s retrospective study used medical records from five Southern California Pediatric Intensive Care Units between September 2009 and June 2011. ...

Haiti can quell cholera without vaccinating most people, UF researchers estimate

2013-01-10

GAINESVILLE, Fla. --- Cholera could be contained in Haiti by vaccinating less than half the population, University of Florida researchers suggest in a paper to be published Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports.

The work places UF's Emerging Pathogens Institute in the pro-vaccination camp in an ongoing international debate over how best to contain the two-year-old epidemic that has claimed thousands of lives.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been skeptical about the effectiveness of vaccination against cholera in this setting. It has instead ...

Teenagers with a low muscular strength have a higher risk of dying early form heart disease

2013-01-10

Teenagers with a low muscular strength have a 30% higher risk of committing suicide before the age of 55 years, and a 65% higher risk of developing psychiatric diseases such as depression of schizophrenia. In addition, a low muscular strength during childhood and adolescence is a strong predictor of early death –i.e. before 55 years of age– from cardiovascular disease. A low muscular strength is as powerful a predictor as obesity and high blood pressure.

This was the conclusion drawn in a study recently published in the Medical Journal –a world-leading medical journal– ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Invisible battery parts finally seen with pioneering technique

Tropical forests generate rainfall worth billions, study finds

A yeast enzyme helps human cells overcome mitochondrial defects

Bacteria frozen in ancient underground ice cave found to be resistant against 10 modern antibiotics

Rhododendron-derived drugs now made by bacteria

Admissions for child maltreatment decreased during first phase of COVID-19 pandemic, but ICU admissions increased later

Power in motion: transforming energy harvesting with gyroscopes

Ketamine high NOT related to treatment success for people with alcohol problems, study finds

1 in 6 Medicare beneficiaries depend on telehealth for key medical care

Maps can encourage home radon testing in the right settings

Exploring the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline

Machine learning tool can predict serious transplant complications months earlier

Prevalence of over-the-counter and prescription medication use in the US

US child mental health care need, unmet needs, and difficulty accessing services

Incidental rotator cuff abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging

Sensing local fibers in pancreatic tumors, cancer cells ‘choose’ to either grow or tolerate treatment

Barriers to mental health care leave many children behind, new data cautions

Cancer and inflammation: immunologic interplay, translational advances, and clinical strategies

Bioactive polyphenolic compounds and in vitro anti-degenerative property-based pharmacological propensities of some promising germplasms of Amaranthus hypochondriacus L.

AI-powered companionship: PolyU interfaculty scholar harnesses music and empathetic speech in robots to combat loneliness

Antarctica sits above Earth’s strongest “gravity hole.” Now we know how it got that way

Haircare products made with botanicals protects strands, adds shine

Enhanced pulmonary nodule detection and classification using artificial intelligence on LIDC-IDRI data

Using NBA, study finds that pay differences among top performers can erode cooperation

Korea University, Stanford University, and IESGA launch Water Sustainability Index to combat ESG greenwashing

Molecular glue discovery: large scale instead of lucky strike

Insulin resistance predictor highlights cancer connection

Explaining next-generation solar cells

Slippery ions create a smoother path to blue energy

Magnetic resonance imaging opens the door to better treatments for underdiagnosed atypical Parkinsonisms

[Press-News.org] Study quantifies the size of holes antibacterials create in cell walls to kill bacteriaDeath on a nanometer scale