(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Researchers have shown that transplanting stem cells derived from normal mouse blood vessels into the hearts of mice that model the pathology associated with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) prevents the decrease in heart function associated with DMD.

Their findings appear in the journal Stem Cells Translational Medicine.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the gene for dystrophin, a protein that anchors muscle cells in place when they contract. Without dystrophin, muscle contractions tear cell membranes, leading to cell death. The lost muscle cells must be regenerated, but in time, scar tissue replaces the muscle cells, causing the muscle weakness and heart problems typical of DMD.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that DMD affects one in every 3,500 males. The disease is more prevalent in males because the dystrophin mutation occurs on the X chromosome; males have one X and one Y chromosome, so a male with this mutation will have DMD, while females have two X chromosomes and must have the mutation on both of them to have the disease. Females with the mutation in one X chromosome sometimes develop muscle weakness and heart problems as well, and may pass the mutation on to their children.

Although medical advances have extended the lifespans of DMD patients from their teens or 20s into their early 30s, disease-related damage to the heart and diaphragm still limits their lifespan.

"Almost 100 percent of patients develop dilated cardiomyopathy," in which a weakened heart with enlarged chambers prevents blood from being properly pumped throughout the body, said University of Illinois comparative biosciences professor Suzanne Berry-Miller, who led the study. "Right now, doctors are treating the symptoms of this heart problem by giving patients drugs to try to prolong heart function, but that can't replace the lost or damaged cells," she said.

In the new study, the researchers injected stem cells known as aorta-derived mesoangioblasts (ADM) into the hearts of dystrophin-deficient mice that serve as a model for human DMD. The ADM stem cells have a working copy of the dystrophin gene.

This stem cell therapy prevented or delayed heart problems in mice that did not already show signs of the functional or structural defects typical of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the researchers report.

Berry-Miller and her colleagues do not yet know why the functional benefits occur, but proposed three potential mechanisms. They observed that some of the injected stem cells became new heart muscle cells that expressed the lacking dystrophin protein. The treatment also caused existing stem cells in the heart to divide and become new heart muscle cells, and the stem cells stimulated new blood vessel formation in the heart. It is not yet clear which of these effects is responsible for delaying the onset of cardiomyopathy, Berry-Miller said.

"These vessel-derived cells might be good candidates for therapy, but the more important thing is the results give us new potential therapeutic targets to study, which may be activated directly without the use of cells that are injected into the patient, such as the ADM in the current study," Berry-Miller said. "Activating stem cells that are already present in the body to repair tissue would avoid the potential requirement to find a match between donors and recipients and potential rejection of the stem cells by the patients."

Despite the encouraging results that show that stem cells yield a functional benefit when administered before pathology arises in DMD mouse hearts, a decline in function was seen in mice that already showed the characteristics of dilated cardiomyopathy. One of these characteristics is the replacement of muscle tissue with connective tissue, known as fibrosis.

This difference may occur, Berry-Miller said, as a result of stem cells landing in a pocket of fibrosis rather than in muscle tissue. The stem cells may then become fibroblasts that generate more connective tissue, increasing the amount of scarring and making heart function worse. This shows that the timing of stem cell insertion plays a crucial role in an increase in heart function in mice lacking the dystrophin protein.

She remains optimistic that these results provide a stepping-stone toward new clinical targets for human DMD patients.

"This is the only study so far where a functional benefit has been observed from stem cells in the dystrophin-deficient heart, or where endogenous stem cells in the heart have been observed to produce new muscle cells that replace those lost in DMD, so I think it opens up a new area to focus on in pre-clinical studies for DMD," Berry-Miller said.

INFORMATION:

The Illinois Regenerative Medicine Institute supported this research.

Editor's notes: To reach Suzanne Berry-Miller, call 217-333-4246; email berryse@illinois.edu.

The paper, "Injection of vessel derived stem cells-prevent dilated cardiomyopathy and promote angiogenesis and endogenous cardiac stem cell proliferation in mdx/utrn-/-but not aged mdx mouse models for Duchenne muscular dystrophy," is available online.

Stem-cell approach shows promise for Duchenne muscular dystrophy

2013-01-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Social networks may inflate self-esteem, reduce self-control

2013-01-14

PITTSBURGH/NEW YORK—January 14, 2013— Users of Facebook and other social networks should beware of allowing their self-esteem—boosted by "likes" or positive comments from close friends—to influence their behavior: It could reduce their self-control both on and offline, according to an academic paper by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh and Columbia Business School that has recently been published online in the Journal of Consumer Research.

Titled "Are Close Friends the Enemy? Online Social Networks, Self-Esteem, and Self-Control," the research paper demonstrates ...

Fox Chase researchers discover novel role of the NEDD9 gene in early stages of breast cancer

2013-01-14

PHILADELPHIA, PA (January 14, 2013)—Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths among women in the United States. Many of these deaths occur when there is an initial diagnosis of invasive or metastatic disease. A protein called NEDD9—which regulates cell migration, division and survival—has been linked to tumor invasion and metastasis in a variety of cancers. Researchers at Fox Chase Cancer Center have now shown that NEDD9 plays a surprising role in the early stages of breast tumor development by controlling the growth of progenitor cells that give rise to ...

Pill-sized device provides rapid, detailed imaging of esophageal lining

2013-01-14

Physicians may soon have a new way to screen patients for Barrett's esophagus, a precancerous condition usually caused by chronic exposure to stomach acid. Researchers at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have developed an imaging system enclosed in a capsule about the size of a multivitamin pill that creates detailed, microscopic images of the esophageal wall. The system has several advantages over traditional endoscopy.

"This system gives us a convenient way to screen for Barrett's that doesn't require patient sedation, a ...

The secrets of a tadpole's tail and the implications for human healing

2013-01-14

Scientists at The University of Manchester have made a surprising finding after studying how tadpoles re-grow their tails which could have big implications for research into human healing and regeneration.

It is generally appreciated that frogs and salamanders have remarkable regenerative capacities, in contrast to mammals, including humans. For example, if a tadpole loses its tail a new one will regenerate within a week. For several years Professor Enrique Amaya and his team at The Healing Foundation Centre in the Faculty of Life Sciences have been trying to better understand ...

Cancer suppressor gene links metabolism with cellular aging

2013-01-14

PHILADELPHIA - It is perhaps impossible to overstate the importance of the tumor suppressor gene p53. It is the single most frequently mutated gene in human tumors. p53 keeps pre-cancerous cells in check by causing cells, among other things, to become senescent – aging at the cellular level. Loss of p53 causes cells to ignore the cellular signals that would normally make mutant or damaged cells die or stop growing.

In short, the p53 pathway is an obvious and attractive target for drug developers. But that strategy has so far proven difficult, as most p53 regulatory proteins ...

The genome of diamondback moth provides new clues for sustainable pest management

2013-01-14

January 13, 2013, Fujian and Shenzhen, China- An international research consortium, led by Fujian Agriculture, Forestry University (FAFU) and BGI, has completed the first genome sequence of the diamondback moth (DBM), the most destructive pest of brassica crops. This work provides wider insights into insect adaptation to host plant and opens new ways for more sustainable pest management. The latest study was published online today in Nature Genetics.

The diamondback moth (Plutella xylostella) preferentially feeds on economically important food crops such as rapeseed, cauliflower ...

What did our ancestors look like?

2013-01-14

A new method of establishing hair and eye colour from modern forensic samples can also be used to identify details from ancient human remains, finds a new study published in BioMed Central's open access journal Investigative Genetics. The HIrisPlex DNA analysis system was able to reconstruct hair and eye colour from teeth up to 800 years old, including the Polish General Wladyslaw Sikorski (1881 to 1943) confirming his blue eyes and blond hair.

A team of researchers from Poland and the Netherlands, who recently developed the HIrisPlex system for forensic analysis, have ...

New study reveals gas that triggers ozone destruction

2013-01-14

Scientists at the Universities of York and Leeds have made a significant discovery about the cause of the destruction of ozone over oceans.

They have established that the majority of ozone-depleting iodine oxide observed over the remote ocean comes from a previously unknown marine source.

The research team found that the principal source of iodine oxide can be explained by emissions of hypoiodous acid (HOI) – a gas not yet considered as being released from the ocean – along with a contribution from molecular iodine (I2).

Since the 1970s when methyl iodide (CH3I) was ...

Graphene plasmonics beats the drug cheats

2013-01-14

Writing in Nature Materials, the scientists, working with colleagues from Aix-Marseille University, have created a device which potentially can see one molecule though a simple optical system and can analyse its components within minutes. This uses plasmonics – the study of vibrations of electrons in different materials.

The breakthrough could allow for rapid and more accurate drug testing for professional athletes as it could detect the presence of even trace amounts of a substance.

It could also be used at airports or other high-security locations to prevent would-be ...

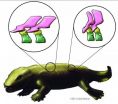

Scientists reassemble the backbone of life with a particle acceleratorynchrotron X-rays

2013-01-14

This press release is available in French and German.

Jointly issued with STFC and the Royal Veterinary College London.

Scientists have been able to reconstruct, for the first time, the intricate three-dimensional structure of the backbone of early tetrapods, the earliest four-legged animals. High-energy X-rays and a new data extraction protocol allowed the researchers to reconstruct the backbones of the 360 million year old fossils in exceptional detail and shed new light on how the first vertebrates moved from water onto land. The results are published 13 January ...