(Press-News.org) MANHATTAN, Kan. -- A Kansas State University-led study has uncovered new information that helps scientists better understand the complex workings of cells in the innate immune system. The findings may also lead to new avenues in disease control and prevention.

Philip Hardwidge, associate professor of diagnostic medicine and pathobiology, was the study's principal investigator. He and colleagues looked at the relationship between a bacterial protein and the innate immune system -- a system of defensive cells that responds rapidly to an infection in a nonspecific manner.

Among their findings, the researchers characterized a new protein that affects how cells in the innate immune system function and protect humans against invading bacteria such as E. coli O157:H7. The study, "NleB, a Bacterial Effector with Glycosyltransferase Activity, Targets GAPDH Function to Inhibit NF-kappaB Activation," was published in the most recent issue of the scientific journal Cell Host and Microbe. The National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases funded the study.

Hardwidge conducted the study with lead author Xiaofei Gao, a doctoral student at the University of Kansas Medical Center and now employed as a postdoctoral fellow at the Whitehead Institute; and with Thanh Pham and Leigh Ann Feuerbacher, postdoctoral research fellows in diagnostic medicine and pathobiology at Kansas State University. Colleagues at the University of Kansas Medical Center; the Institute of Infectiology in Muenster, Germany; and the Stowers Institute for Medical Research also contributed to the study.

The research team studied a bacterium that infects mice, named Citrobacter rodentium. The bacterium is similar to E. coli O157:H7, which causes diarrheal illness in humans. Both bacteria use the protein NleB to inhibit the innate immune system from fighting the bacteria.

"NleB is very important to the ability to cause disease," Hardwidge said. "Epidemiological and functional studies on E. coli and C. rodentium have shown that the presence of the NleB protein is associated with the ability of E. coli and C. rodentium to cause severe disease in humans and mice, respectively. But how the NleB protein did this was unknown."

According to Hardwidge, once bacteria such as C. rodentium and E. coli enter the body, the pathogens use a needle-like secretion apparatus to inject bacterial proteins into intestinal cells. Some of these proteins prevent the innate immune system from fighting the bacterium. One of these injected proteins is NleB.

Hardwidge and colleagues observed that the NleB protein binds with a protein in human cells named GAPDH. NleB modifies the GAPDH protein with a specific sugar molecule and prevents it from participating in a complex biochemical pathway that ultimately allows the innate immune system to respond efficiently to pathogens.

"The function of GAPDH in this pathway was less clear before we did these experiments," Hardwidge said. "GAPDH has well-known functions in the metabolism, but we observed that it also participates in how a cell responds to an infecting bacterium. We're very interested in the fact that this metabolic enzyme has apparently evolved also to be an important part of the innate immune system."

Hardwidge said that E. coli and C. rodentium using the NleB protein to target GAPDH and inhibit innate immunity is also an interesting finding, which will be characterized in greater detail in continuing studies.

With a more advanced understanding about how the innate immune system responds biochemically to invading bacteria -- and how those bacteria suppress the response -- scientists may be able to advance research and therapeutic drug development in other diseases, Hardwidge said. For example, cancers, Crohn's disease and Rheumatoid arthritis all are tied to overactive inflammation. In some cases, the same pathway in which GAPDH participates regulates the inflammation.

"The cell is so complicated, it's amazing that it even works at all, especially when you consider that it is three-dimensional and compartmentalized," Hardwidge said. "We have a general understanding about this important pathway that triggers a defensive response. But when you get into the details of how this pathway is regulated, we're still learning and understanding what exactly is going on. Now, low and behold, there is a new protein involved."

### END

Immunology research sheds new light on cell function, response

2013-01-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NASA's Webb telescope team completes optical milestone

2013-01-17

GREENBELT, Md. -- Engineers working on NASA's James Webb Space Telescope met another milestone recently with they completed performance testing on the observatory's aft-optics subsystem at Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp's facilities in Boulder, Colo. Ball is the principal subcontractor to Northrop Grumman for the optical technology and lightweight mirror system.

"Completing Aft Optics System performance testing is significant because it means all of the telescope's mirror systems are ready for integration and testing," said Lee Feinberg, NASA Optical Telescope Element ...

NASA sees 1 area of strength in Tropical Storm Emang

2013-01-17

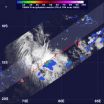

Tropical Storm Emang continues to move through open waters in the Southern Indian Ocean and NASA's TRMM satellite noticed one area of heavy rainfall near the center.

On Jan. 16 at 0702 UTC (2:02 a.m. EST) NASA's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite passed over Emang, and captured rainfall rates. TRMM identified that moderate rain was falling throughout most of the tropical cyclone, and heavy rainfall was occurring near the storm's center. TRMM estimated the heavy rain falling at a rate of 2 inches (50 mm) per hour.

On Jan. 16 at 0900 UTC (4 a.m. EST), ...

Gene in eye melanomas linked to good prognosis

2013-01-17

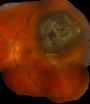

Melanomas that develop in the eye often are fatal. Now, scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report they have identified a mutated gene in melanoma tumors of the eye that appears to predict a good outcome.

The research is published in the advance online edition of Nature Genetics.

"We found mutations in a gene called SF3B1," says senior author Anne Bowcock, PhD, professor of genetics. "The good news is that these mutations develop in a distinct subtype of melanomas in the eye that are unlikely to spread and become deadly."

Eye tumors ...

Mayo Clinic: Skin problems, joint disorders top list of reasons people visit doctors

2013-01-17

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- A new Mayo Clinic Proceedings study shows that people most often visit their health care providers because of skin issues, joint disorders and back pain. Findings may help researchers focus efforts to determine better ways to prevent and treat these conditions in large groups of people.

"Much research already has focused on chronic conditions, which account for the majority of health care utilization and costs in middle-aged and older adults," says Jennifer St. Sauver, Ph.D., primary author of the study and member of the Population Health Program within ...

Eliminating or curtailing mortgage interest deduction would have modest long-run effects on economy

2013-01-17

Eliminating or curtailing the mortgage interest deduction (MID) would initially result in declines in housing prices and investment but would have only modest aggregate macroeconomic effects in the long run, according to a new paper from Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy.

The MID is the second-largest individual income tax expenditure, according to the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation. Given the severity of the fiscal problems currently faced by the U.S., many recent tax reform proposals have included measures that would curtail or eliminate ...

Recent study suggests bats are reservoir for ebola virus in Bangladesh

2013-01-17

NEW YORK – January 16, 2013 – EcoHealth Alliance, a nonprofit organization that focuses on local conservation and global health issues, released new research on Ebola virus in fruit bats in the peer reviewed journal, Emerging Infectious Diseases, a monthly publication by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The study found Ebola virus antibodies circulating in ~4% of the 276 bats scientists screened in Bangladesh. These results suggest that Rousettus fruit bats are a reservoir for Ebola, or a new Ebola-like virus in South Asia. The study extends the range ...

Tree and human health may be linked

2013-01-17

Evidence is increasing from multiple scientific fields that exposure to the natural environment can improve human health. In a new study by the U.S. Forest Service, the presence of trees was associated with human health.

For Geoffrey Donovan, a research forester at the Forest Service's Pacific Northwest Research Station, and his colleagues, the loss of 100 million trees in the eastern and midwestern United States was an unprecedented opportunity to study the impact of a major change in the natural environment on human health.

In an analysis of 18 years of data from ...

PODEX experiment to reshape future of atmospheric science

2013-01-17

Satellite Earth science missions don't start at the launch pad or even in orbit. They start years before when scientists test their new ideas for instruments that promise to expand our view and understanding of the planet. NASA scientists and engineers are working now to lay the groundwork for the Aerosol-Cloud-Ecosystem (ACE) mission, a satellite that "will dramatically change what we can do from space to learn about clouds and aerosols," said ACE science lead David Starr of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

How should the satellite's instruments be ...

Risk factors identified for prolonged sports concussion symptoms

2013-01-17

Researchers have found clear, identifiable factors that signal whether an athlete will experience concussive symptoms beyond one week. The researchers sought to identify risk factors for prolonged concussion symptoms by examining a large national database of high school athletes' injuries. Previous concussion studies were limited in scope, focusing only on male football players. The information from this study applies to male and female athletes from a number of different sports.

Researchers found that athletes who have four or more symptoms at initial injury were more ...

New research finds slower growth of preterm infants linked to altered brain development

2013-01-17

Preterm infants who grow more slowly as they approached what would have been their due dates also have slower development in an area of the brain called the cerebral cortex, report Canadian researchers in a new study published today in Science Translational Medicine.

The cerebral cortex is a two to four millimetre layer of cells that envelopes the top part of the brain and is involved in cognitive, behavioural, and motor processes.

Researchers analyzed MRI brain scans of 95 preterm infants born eight to 16 weeks too early at

BC Women's Hospital & Health Centre between ...