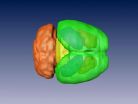

(Press-News.org) People who take cocaine over many years without becoming addicted have a brain structure which is significantly different from those individuals who developed cocaine-dependence, researchers have discovered. New research from the University of Cambridge has found that recreational drug users who have not developed a dependence have an abnormally large frontal lobe, the section of the brain implicated in self-control. Their research was published in the journal Biological Psychiatry.

For the study, led by Dr Karen Ersche, individuals who use cocaine on a regular basis underwent a brain scan and completed a series of personality tests. The majority of the cocaine users were addicted to the drug but some were not (despite having used it for several years).

The scientists discovered that a region in the frontal lobes of the brain, known to be critically implicated in decision-making and self-control, was abnormally bigger in the recreational cocaine users. The Cambridge researchers suggest that this abnormal increase in grey matter volume, which they believe predates drug use, might reflect resilience to the effects of cocaine, and even possibly helps these recreational cocaine users to exert self-control and to make advantageous decisions which minimize the risk of them becoming addicted.

They found that this same region in the frontal lobes of the brain was significantly reduced in size in people with cocaine dependence, confirming earlier research that had found similar results. They believe that at least some of these changes are the result of drug use, which causes drug users to lose grey matter.

They also found that people who use illicit drugs like cocaine exhibit high levels of sensation-seeking personality traits, but only those developing dependence show personality traits of impulsivity and compulsivity.

Dr Ersche, of the Behavioural and Clinical Neuroscience Institute (BCNI) at the University of Cambridge, said: "These findings are important because they show that the use of cocaine does not inevitably lead to addiction in people with good self-control and no familial risk.

"Our findings indicate that preventative strategies might be more effective if they were tailored more closely to those individuals at risk according to their personality profile and brain structure."

The researchers will next explore the basis of the recreational users' apparent resilience to drug dependence.

Dr Ersche added: "Their high level of education, less troubled family background or the beginning of drug-taking only after puberty may all play a role."

###

For additional information please contact:

Genevieve Maul

Office of Communications

University of Cambridge

Tel: 44-1223-332-300

Mob: 44-7774-017-464

Email: Genevieve.maul@admin.cam.ac.uk

Notes to editors:

1. The paper 'Distinctive Personality Traits and Neural Correlates Associated with Stimulant Drug Use Versus Familial Risk of Stimulant Dependence' was published in Biological Psychiatry.

2. This work was funded by a Medical Research Council (G0701497) and received institutional funds from the Behavioural and Clinical Neuroscience Institute (BCNI), which is jointly funded by the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust. END

People with low risk for cocaine dependence have differently shaped brain to those with addiction

Research provides unique insight into the often misunderstood world of addiction

2013-01-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Cheating to create the perfect simulation

2013-01-17

(Jena) The planet Earth will die – if not before, then when the Sun collapses. This is going to happen in approximately seven billion years. In the universe however the death of suns and planets is an everyday occurance and our solar system partly consists of their remnants.

The end of stars – suns – rich in mass is often a neutron star. These "stars' liches" demonstrate a high density, in which atoms are extremely compressed. Such neutron stars are no bigger than a small town, but heavier than our sun, as physicist PD Dr. Axel Maas of the Jena University (Germany) points ...

Dietary shifts driving up phosphorus use

2013-01-17

Dietary changes since the early 1960s have fueled a sharp increase in the amount of mined phosphorus used to produce the food consumed by the average person over the course of a year, according to a new study led by researchers at McGill University.

Between 1961 and 2007, rising meat consumption and total calorie intake underpinned a 38% increase in the world's per capita "phosphorus footprint," the researchers conclude in a paper published online in Environmental Research Letters.

The findings underscore a significant challenge to efforts to sustainably manage the ...

Viagra converts fat cells

2013-01-17

Researchers from the University of Bonn treated mice with Viagra and made an amazing discovery: The drug converts undesirable white fat cells and could thus potentially melt the unwelcome "spare tire" around the midriff. In addition, the substance also decreases the risk of other complications caused by obesity. The results are now published in "The Journal of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology" (FASEB).

Sildenafil – better known as Viagra – is used to treat erectile dysfunction. This substance prevents degradation of cyclic guanosine mono-phosphate ...

Is athleticism linked to brain size?

2013-01-17

VIDEO:

This movie shows running mice (bred-for-athleticism mouse on the left, regular mouse on the right).

Click here for more information.

RIVERSIDE, Calif. — Is athleticism linked to brain size? To find out, researchers at the University of California, Riverside performed laboratory experiments on house mice and found that mice that have been bred for dozens of generations to be more exercise-loving have larger midbrains than those that have not been selectively bred ...

Fighting sleep: UGA discovery may lead to new treatments for deadly sleeping sickness

2013-01-17

Athens, Ga. – While its common name may make it sound almost whimsical, sleeping sickness, or African trypanosomiasis, is in reality a potentially fatal parasitic infection that has ravaged populations in sub-Saharan Africa for decades, and it continues to infect thousands of people every year.

Few drugs have been developed to treat sleeping sickness since the 1940s, and those still in use are highly toxic, sometimes causing painful side effects and even death. But researchers at the University of Georgia have made a discovery that may soon lead to new therapies for this ...

Critically ill flu patients saved with artificial lung technology treatment

2013-01-17

TORONTO (January 17, 2013 ) - In recent weeks the intensive critical care units at University Health Network's Toronto General Hospital have used Extra Corporeal Lung Support (ECLS) to support five influenza (flu) patients in their recovery from severe respiratory problems.

ECLS systems are normally used at the hospital as a bridge to lung transplantation but increasingly, the hospital is using ECLS on patients where the usual breathing machines (ventilators) cannot support the patient whose lungs need time to rest and heal.

The ECLS systems are essentially artificial ...

Drug abuse impairs sexual performance in men even after rehabilitation

2013-01-17

Researchers at the University of Granada, Spain, and Santo Tomas University in Colombia have found that drug abuse negatively affects sexual performance in men even after years of abstinence. This finding contradicts other studies reporting that men spontaneously recovered their normal sexual performance at three weeks after quitting substance abuse.

The results of this study have been published in the prestigious Journal of Sexual Medicine, the official journal of the International Society for Sexual Medicine. The authors of this paper are Pablo Vallejo Medina –a professor ...

Trading wetlands no longer a deal with the devil

2013-01-17

URBANA – If Faust had been in the business of trading wetlands rather than selling his soul, the devil might be portrayed by the current guidelines for wetland restoration. Research from the University of Illinois recommends a new framework that could make Faustian bargains over wetland restoration sites result in more environmentally positive outcomes.

U of I ecologist Jeffrey Matthews explained that under the current policies if a wetland is scheduled for development and a negative impact is unavoidable, the next option is to offset, or compensate, for the destruction ...

UNC researchers use luminescent mice to track cancer and aging in real-time

2013-01-17

Chapel Hill, NC – In a study published in the January 18 issue of Cell, researchers from the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center have developed a new method to visualize aging and tumor growth in mice using a gene closely linked to these processes.

Researchers have long known that the gene, p16INK4a (p16), plays a role in aging and cancer suppression by activating an important tumor defense mechanism called 'cellular senescence'. The UNC team led by Norman Sharpless, MD, Wellcome Distinguished Professor of Cancer Research and Deputy Cancer ...

How are middle-aged women affected by burnout?

2013-01-17

New Rochelle, NY, January 17, 2013—Emotional exhaustion and physical and cognitive fatigue are signs of burnout, often caused by prolonged exposure to stress. Burnout can cause negative health effects including poor sleep, depression, anxiety, and cardiovascular and immune disorders. The findings of a 9-year study of burnout in middle-aged working women are reported in an article in Journal of Women's Health, a peer-reviewed publication from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. The article is available free on the Journal of Women's Health website at http://www.liebertpub.com/jwh.

In ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Does online sports gambling affect substance use behaviors?

How do rapid socio-environmental transitions reshape cancer risk?

Do abortion bans affect birth rates and food-assistance costs?

Can artificial intelligence help reduce the carbon footprint of weather forecasting models?

Mangrove forests are short of breath

Low testosterone, high fructose: A recipe for liver disaster

SKKU research team unravels the origin of stochasticity, a key to next-generation data security and computing

Flexible polymer‑based electronics for human health monitoring: A safety‑level‑oriented review of materials and applications

Could ultrasound help save hedgehogs?

attexis RCT shows clinically relevant reduction in adult ADHD symptoms and is published in Psychological Medicine

Cellular changes linked to depression related fatigue

First degree female relatives’ suicidal intentions may influence women’s suicide risk

Specific gut bacteria species (R inulinivorans) linked to muscle strength

Wegovy may have highest ‘eye stroke’ and sight loss risk of semaglutide GLP-1 agonists

New African species confirms evolutionary origin of magic mushrooms

Mining the dark transcriptome: University of Toronto Engineering researchers create the first potential drug molecules from long noncoding RNA

IU researchers identify clotting protein as potential target in pancreatic cancer

Human moral agency irreplaceable in the era of artificial intelligence

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

[Press-News.org] People with low risk for cocaine dependence have differently shaped brain to those with addictionResearch provides unique insight into the often misunderstood world of addiction