(Press-News.org) PORTLAND, Ore. – Physician-scientists at Oregon Health & Science University Doernbecher Children's Hospital are challenging the way pediatric neurologists think about brain injury in the pre-term infant. In a study published online in the Jan. 16 issue of Science Translational Medicine, the OHSU Doernbecher researchers report for the first time that low blood and oxygen flow to the developing brain does not, as previously thought, cause an irreversible loss of brain cells, but rather disrupts the cells' ability to fully mature. This discovery opens up new avenues for potential therapies to promote regeneration and repair of the premature brain.

"As neurologists, we thought ischemia killed the neurons and that they were irreversibly lost from the brain. But this new data challenges that notion by showing that ischemia, or low blood flow to the brain, can alter the maturation of the neurons without causing the death of these cells. As a result, we can focus greater attention on developing the right interventions, at the right time early in development, to promote neurons to more fully mature and reduce the often serious impact of preterm birth. We now we have a much more hopeful scenario," said Stephen Back, M.D., Ph.D., lead investigator and professor of pediatrics and neurology in the Papé Family Pediatric Research Institute at OHSU Doernbecher Children's Hospital.

Researchers at OHSU Doernbecher have conducted a number of studies in preterm fetal sheep to define how disturbances in brain blood flow lead to injury in the developing brain. Their findings have led to important advances in the care of critically ill newborn infants.

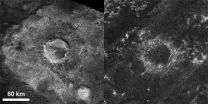

For this study, Back and colleagues used pioneering new MRI studies that allow injury to the developing brain to be identified much earlier than previously feasible. They looked at the cerebral cortex, or "thinking" part of the brain, which controls the complex tasks involved with learning, attention and social behaviors that are frequently impaired in children who survive preterm birth. Specifically, they observed how brain injury in the cerebral cortex of fetal sheep evolved over one month and found no evidence that cells were dying or being lost. They did notice, however, that more brain cells were packed into a smaller volume of brain tissue, which led to, upon further examination, the discovery that the brain cells weren't fully mature.

In a related study published in the same online issue of Science Translational Medicine, investigators at The Hospital for Sick Children and the University of Toronto studied 95 premature infants using MRI and found that impaired growth of the infants was the strongest predictor of the MRI abnormalities, suggesting that interventions to improve infant nutrition and growth may lead to improved cortical development.

"I believe these studies provide hope for the future for preterm babies with brain injury, because our findings suggest that neurons are not being permanently lost from the human cerebral cortex due to ischemia. This raises the possibility that neurodevelopmental enrichment — or perhaps improved early infant nutrition — as suggested by the companion paper, might make a difference in terms of improved cognitive outcome," Back said.

"Together, these studies challenge the conventional wisdom that preterm birth is associated with a loss of cortical neurons. This finding may change the way neurologists think about diagnosing and treating children born prematurely," said Jill Morris, Ph.D., a program director at the National Institute's of Health's National Institute Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

More than 65,000 premature babies are born in the United States each year. Children who survive preterm birth commonly suffer from a wide range of life-long disabilities, including impaired walking due to cerebral palsy. Currently, children have a 10 times greater risk of acquiring cerebral palsy than of being diagnosed with cancer. By the time they reach school age, between 25 and 50 percent of children born prematurely are also identified with a wide range of learning disabilities, social impairment and attention deficit disorders.

INFORMATION:

This study, "Prenatal Cerebral Ischemia Disrupts MRI-Defined Cortical Microstructure Through Disturbances in Neuronal Arborization," was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P51RR000163 and NCRR P51 RR000113; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grants 1RO1NS054044 and R37NS045737, R37NS045737-06S1/06S2 and 1F30NS066704; a Bugher Award from the American Heart Association; March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation; and a Heubner Family Neurobiology of Disease Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Particulars

Oregon Health & Science University and its children's hospital, OHSU Doernbecher Children's Hospital, are nationally recognized for their research and clinical emphasis on white matter disorders of the brain. Several OHSU and OHSU Doernbecher groups contributed to this study as a collaborative team led by Stephen A. Back, M.D., Ph.D.

Back has a long-standing research program focused on white matter disorders in children and adults that is supported by a Javits Neuroscience Investigator Award from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Chris Kroenke, Ph.D., an associate scientist in OHSU's Advanced Imaging Research Center led the team that performed the high-field MRI studies. Dr. Kroenke has the specialized expertise required to analyze MRI signals coming from the developing brain. A. Roger Hohimer, Ph.D., an associate professor at OHSU provided the specialize expertise to study the physiology of the fetal brain injury model. Justin Dean, Ph.D., the first author on the study, was a post-doctoral fellow in Dr. Back's lab and is currently an assistant professor in the Department of Physiology at the University of Auckland, New Zealand.

About OHSU Doernbecher Children's Hospital

OHSU Doernbecher Children's Hospital ranks among the top 50 children's hospitals in the United States and is one of only 22 NIH-designated Child Health Research Centers in the country. OHSU Doernbecher cares for tens of thousands of children each year from Oregon, Southwest Washington and around the nation, resulting in more than 175,000 discharges, surgeries, transports and outpatient visits annually. Nationally recognized OHSU Doernbecher physicians and nurses provide a full range of pediatric care in the most patient- and family-centered environment, and travel throughout Oregon and southwest Washington, providing specialty care to more than 3,000 children at more than 150 outreach clinics in 15 locations. OHSU Doernbecher also delivers neonatal and pediatric critical care consultation to community hospitals statewide through its state-of-the-art telemedicine network.

Study findings have potential to prevent,reverse disabilities in children born prematurely

Research conducted at OHSU Doernbecher Children's Hospital challenges long-held belief that low blood flow to the premature brain necessarily kills brain cells

2013-01-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Want to ace that interview? Make sure your strongest competition is interviewed on a different day

2013-01-18

Whether an applicant receives a high or low score may have more to do with who else was interviewed that day than the overall strength of the applicant pool, according to new research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

Drawing on previous research on the gambler fallacy, Uri Simonsohn of The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and Francesca Gino of Harvard Business School hypothesized that admissions interviewers would have a difficult time seeing the forest for the trees. Instead of evaluating applicants ...

In minutes a day, low-income families can improve their kids' health

2013-01-18

URBANA – When low-income families devote three to four extra minutes to regular family mealtimes, their children's ability to achieve and maintain a normal weight improves measurably, according to a new University of Illinois study.

"Children whose families engaged with each other over a 20-minute meal four times a week weighed significantly less than kids who left the table after 15 to 17 minutes. Over time, those extra minutes per meal add up and become really powerful," said Barbara H. Fiese, director of the U of I's Family Resiliency Program.

Childhood obesity ...

Understanding personality for decision-making, longevity, and mental health

2013-01-18

January 17, 2013 – New Orleans – Extraversion does not just explain differences between how people act at social events. How extraverted you are may influence how the brain makes choices – specifically whether you choose an immediate or delayed reward, according to a new study. The work is part of a growing body of research on the vital role of understanding personality in society.

"Understanding how people differ from each other and how that affects various outcomes is something that we all do on an intuitive basis, but personality psychology attempts to bring scientific ...

World's most complex 2-D laser beamsteering array demonstrated

2013-01-18

Most people are familiar with the concept of RADAR. Radio frequency (RF) waves travel through the atmosphere, reflect off of a target, and return to the RADAR system to be processed. The amount of time it takes to return correlates to the object's distance. In recent decades, this technology has been revolutionized by electronically scanned (phased) arrays (ESAs), which transmit the RF waves in a particular direction without mechanical movement. Each emitter varies its phase and amplitude to form a RADAR beam in a particular direction through constructive and destructive ...

NASA beams Mona Lisa to Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter at the moon

2013-01-18

VIDEO:

NASA Goddard scientists transmitted an image of the Mona Lisa from Earth to the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter at the moon by piggybacking on laser pulses that routinely track the spacecraft.

HD...

Click here for more information.

As part of the first demonstration of laser communication with a satellite at the moon, scientists with NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) beamed an image of the Mona Lisa to the spacecraft from Earth.

The iconic image traveled ...

Titan gets a dune 'makeover'

2013-01-18

Titan's siblings must be jealous. While most of Saturn's moons display their ancient faces pockmarked by thousands of craters, Titan – Saturn's largest moon – may look much younger than it really is because its craters are getting erased. Dunes of exotic, hydrocarbon sand are slowly but steadily filling in its craters, according to new research using observations from NASA's Cassini spacecraft.

"Most of the Saturnian satellites – Titan's siblings – have thousands and thousands of craters on their surface. So far on Titan, of the 50 percent of the surface that we've seen ...

Stroke survivors with PTSD more likely to avoid treatment

2013-01-18

New York, NY — A new survey of stroke survivors has shown that those with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are less likely to adhere to treatment regimens that reduce the risk of an additional stroke. Researchers found that 65 percent of stroke survivors with PTSD failed to adhere to treatment, compared with 33 percent of those without PTSD. The survey also suggests that nonadherence in PTSD patients is partly explained by increased ambivalence toward medication. Among stroke survivors with PTSD, approximately one in three (38 percent) had concerns about their medications. ...

Severity of emphysema predicts mortality

2013-01-18

Severity of emphysema, as measured by computed tomography (CT), is a strong independent predictor of all-cause, cardiovascular, and respiratory mortality in ever-smokers with or without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), according to a study from researchers in Norway. In patients with severe emphysema, airway wall thickness is also associated with mortality from respiratory causes.

"Ours is the first study to examine the relationship between degree of emphysema and mortality in a community-based sample and between airway wall thickness and mortality," said ...

Researchers find that simple blood test can help identify trauma patients at greatest risk of death

2013-01-18

SALT LAKE CITY – A simple, inexpensive blood test performed on trauma patients upon admission can help doctors easily identify patients at greatest risk of death, according to a new study by researchers at Intermountain Medical Center in Salt Lake City.

The Intermountain Medical Center research study of more than 9,500 patients discovered that some trauma patients are up to 58 times more likely to die than others, regardless of the severity of their original injuries.

Researchers say the study findings provide important insight into the long-term prognosis of trauma ...

UGA researchers invent new material for warm-white LEDs

2013-01-18

Athens, Ga. – Light emitting diodes, more commonly called LEDs, are known for their energy efficiency and durability, but the bluish, cold light of current white LEDs has precluded their widespread use for indoor lighting.

Now, University of Georgia scientists have fabricated what is thought to be the world's first LED that emits a warm white light using a single light emitting material, or phosphor, with a single emitting center for illumination. The material is described in detail in the current edition of the Nature Publishing Group journal "Light: Science and Applications."

"Right ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Brain cells drive endurance gains after exercise

Same-day hospital discharge is safe in selected patients after TAVI

Why do people living at high altitudes have better glucose control? The answer was in plain sight

Red blood cells soak up sugar at high altitude, protecting against diabetes

A new electrolyte points to stronger, safer batteries

Environment: Atmospheric pollution directly linked to rocket re-entry

Targeted radiation therapy improves quality of life outcomes for patients with multiple brain metastases

Cardiovascular events in women with prior cervical high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

Transplantation and employment earnings in kidney transplant recipients

Brain organoids can be trained to solve a goal-directed task

Treatment can protect extremely premature babies from lung disease

Roberto Morandotti wins prestigious Max Born Award for pioneering research in quantum photonics

Scientists map brain's blood pressure control center

Acute coronary events registry provides insights into sex-specific differences

Bar-Ilan University and NVIDIA researchers improve AI’s ability to understand spatial instructions

New single-cell transcriptomic clock reveals intrinsic and systemic T cell aging in COVID-19 and HIV

Smaller fish and changing food webs – even where species numbers stay the same

Missed opportunity to protect pregnant women and newborns: Study shows low vaccination rates among expectant mothers in Norway against COVID-19 and influenza

Emotional memory region of aged brain is sensitive to processed foods

Neighborhood factors may lead to increased COPD-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations

Food insecurity impacts employees’ productivity

Prenatal infection increases risk of heavy drinking later in life

‘The munchies’ are real and could benefit those with no appetite

FAU researchers discover novel bacteria in Florida’s stranded pygmy sperm whales

DEGU debuts with better AI predictions and explanations

‘Giant superatoms’ unlock a new toolbox for quantum computers

Jeonbuk National University researchers explore metal oxide electrodes as a new frontier in electrochemical microplastic detection

Cannabis: What is the profile of adults at low risk of dependence?

Medical and materials innovations of two women engineers recognized by Sony and Nature

Blood test “clocks” predict when Alzheimer’s symptoms will start

[Press-News.org] Study findings have potential to prevent,reverse disabilities in children born prematurelyResearch conducted at OHSU Doernbecher Children's Hospital challenges long-held belief that low blood flow to the premature brain necessarily kills brain cells