(Press-News.org) CHESTNUT HILL, MA (Jan. 17, 2013) – A new study that looked at more than 75,000 children in day care in Norway found little evidence that the amount of time a child spends in child care leads to an increase in behavioral problems, according to researchers from the United States and Norway.

Several prior studies in the U.S. made connections between the time a child spends in day care and behavioral problems, but the results from Norway contradict those earlier findings, the researchers report in the online version of the journal Child Development.

"In Norway, we do not find that children who spend a significant amount of time in child care have more behavior problems than other children," Boston College Associate Professor of Education Eric Dearing, a co-author of the report, said. "This runs counter to several US studies that have shown a correlation between time in child care and behavior problems."

Dearing, who conducted the study with researchers from Norway and Harvard Medical School, said the Scandinavian country's approach to child care might explain why so few behavioral problems were found among children included in the study group.

In Norway, parental leave policies ensure that most children do not enter child care until the age of one. In addition, unlike the U.S., Norway maintains national standards and regulations for child care providers, which may lead to higher quality care, said Dearing.

"Norway takes a very different approach to child care than we do in the United States and that may play a role in our findings," said Dearing, an expert in child development, who co-authored the study with Dr. Claudio O. Toppelberg, a psychiatrist and researcher with Harvard Medical School and its Judge Baker Children's Center, and Norwegian researchers Henrik D. Zachrisson and Ratib Lekhal.

With a large sample size capable of revealing even the narrowest of connections between early care and behavior, the team went through a number of statistical tests to examine methods used in earlier U.S. studies and to scrutinize their own findings.

When the researchers examined the sample using methods identical to those most commonly used in U.S. studies, they produced a similar link between child care hours and behavior. But the researchers took issue with the common approach, which is to compare children from different families who spend varying amounts of time in child care because of family choices. Although earlier U.S. studies using this method tried to control for parent and family characteristics – such as income and education, mental health and intelligence – the method leaves open the possibility that differences between families in areas other than child care choices are, in fact, the true causes of behavior problems.

Given the scope the Norwegian data, the researchers were able to compare children who came from the same families but who spent varying hours in child care, effectively resolving the issue of external influences. When they did this, they found no statistical evidence to point to increased behavioral problems. Siblings who spent more time in day care exhibited the same behavior as siblings who spent less time in day care, Dearing said.

The researchers went even further, probing the sample in an effort to reveal even the most minor, yet statistically significant, links between hours spent in child care and behavioral problems.

"The biggest surprise was that we found so little evidence of a relation between child care hours and behavior once we introduced conservative controls in an effort to ensure that any association was in fact causal," said Dearing. "With such a very large sample, even very, very small correlations would be statistically significant. But we found no association in our most sophisticated models."

Dearing and colleagues report that important next steps will be follow-up studies involving Norwegian children into later childhood and adolescence, times through which child care effects persist in the US, and collecting more data from countries outside the US to determine the child and family policy environments in which child care does or does not appear to put children at risk.

### END

New study challenges links between day care and behavioral issues

2013-01-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study findings have potential to prevent,reverse disabilities in children born prematurely

2013-01-18

PORTLAND, Ore. – Physician-scientists at Oregon Health & Science University Doernbecher Children's Hospital are challenging the way pediatric neurologists think about brain injury in the pre-term infant. In a study published online in the Jan. 16 issue of Science Translational Medicine, the OHSU Doernbecher researchers report for the first time that low blood and oxygen flow to the developing brain does not, as previously thought, cause an irreversible loss of brain cells, but rather disrupts the cells' ability to fully mature. This discovery opens up new avenues for potential ...

Want to ace that interview? Make sure your strongest competition is interviewed on a different day

2013-01-18

Whether an applicant receives a high or low score may have more to do with who else was interviewed that day than the overall strength of the applicant pool, according to new research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

Drawing on previous research on the gambler fallacy, Uri Simonsohn of The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and Francesca Gino of Harvard Business School hypothesized that admissions interviewers would have a difficult time seeing the forest for the trees. Instead of evaluating applicants ...

In minutes a day, low-income families can improve their kids' health

2013-01-18

URBANA – When low-income families devote three to four extra minutes to regular family mealtimes, their children's ability to achieve and maintain a normal weight improves measurably, according to a new University of Illinois study.

"Children whose families engaged with each other over a 20-minute meal four times a week weighed significantly less than kids who left the table after 15 to 17 minutes. Over time, those extra minutes per meal add up and become really powerful," said Barbara H. Fiese, director of the U of I's Family Resiliency Program.

Childhood obesity ...

Understanding personality for decision-making, longevity, and mental health

2013-01-18

January 17, 2013 – New Orleans – Extraversion does not just explain differences between how people act at social events. How extraverted you are may influence how the brain makes choices – specifically whether you choose an immediate or delayed reward, according to a new study. The work is part of a growing body of research on the vital role of understanding personality in society.

"Understanding how people differ from each other and how that affects various outcomes is something that we all do on an intuitive basis, but personality psychology attempts to bring scientific ...

World's most complex 2-D laser beamsteering array demonstrated

2013-01-18

Most people are familiar with the concept of RADAR. Radio frequency (RF) waves travel through the atmosphere, reflect off of a target, and return to the RADAR system to be processed. The amount of time it takes to return correlates to the object's distance. In recent decades, this technology has been revolutionized by electronically scanned (phased) arrays (ESAs), which transmit the RF waves in a particular direction without mechanical movement. Each emitter varies its phase and amplitude to form a RADAR beam in a particular direction through constructive and destructive ...

NASA beams Mona Lisa to Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter at the moon

2013-01-18

VIDEO:

NASA Goddard scientists transmitted an image of the Mona Lisa from Earth to the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter at the moon by piggybacking on laser pulses that routinely track the spacecraft.

HD...

Click here for more information.

As part of the first demonstration of laser communication with a satellite at the moon, scientists with NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) beamed an image of the Mona Lisa to the spacecraft from Earth.

The iconic image traveled ...

Titan gets a dune 'makeover'

2013-01-18

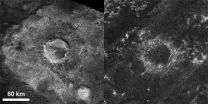

Titan's siblings must be jealous. While most of Saturn's moons display their ancient faces pockmarked by thousands of craters, Titan – Saturn's largest moon – may look much younger than it really is because its craters are getting erased. Dunes of exotic, hydrocarbon sand are slowly but steadily filling in its craters, according to new research using observations from NASA's Cassini spacecraft.

"Most of the Saturnian satellites – Titan's siblings – have thousands and thousands of craters on their surface. So far on Titan, of the 50 percent of the surface that we've seen ...

Stroke survivors with PTSD more likely to avoid treatment

2013-01-18

New York, NY — A new survey of stroke survivors has shown that those with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are less likely to adhere to treatment regimens that reduce the risk of an additional stroke. Researchers found that 65 percent of stroke survivors with PTSD failed to adhere to treatment, compared with 33 percent of those without PTSD. The survey also suggests that nonadherence in PTSD patients is partly explained by increased ambivalence toward medication. Among stroke survivors with PTSD, approximately one in three (38 percent) had concerns about their medications. ...

Severity of emphysema predicts mortality

2013-01-18

Severity of emphysema, as measured by computed tomography (CT), is a strong independent predictor of all-cause, cardiovascular, and respiratory mortality in ever-smokers with or without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), according to a study from researchers in Norway. In patients with severe emphysema, airway wall thickness is also associated with mortality from respiratory causes.

"Ours is the first study to examine the relationship between degree of emphysema and mortality in a community-based sample and between airway wall thickness and mortality," said ...

Researchers find that simple blood test can help identify trauma patients at greatest risk of death

2013-01-18

SALT LAKE CITY – A simple, inexpensive blood test performed on trauma patients upon admission can help doctors easily identify patients at greatest risk of death, according to a new study by researchers at Intermountain Medical Center in Salt Lake City.

The Intermountain Medical Center research study of more than 9,500 patients discovered that some trauma patients are up to 58 times more likely to die than others, regardless of the severity of their original injuries.

Researchers say the study findings provide important insight into the long-term prognosis of trauma ...