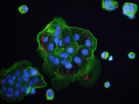

(Press-News.org) CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Cells in the immune system called macrophages normally engulf and kill intruding bacteria, holding them inside a membrane-bound bag called a vacuole, where they kill and digest them.

Some bacteria thwart this effort by ripping the bag open and then escaping into the macrophage's nutrient-rich cytosol compartment, where they divide and could eventually go on to invade other cells.

But research from the University of North Carolina School of Medicine shows that macrophages have a suicide alarm system, a signaling pathway to detect this escape into the cytosol. The pathway activates an enzyme, called caspase-11, that triggers a program in the macrophage to destroy itself.

"It's almost like a thief sneaking into the house not knowing an alarm will go off to knock down the walls and expose him to capture by the police," says study senior and corresponding author Edward Miao, PhD, assistant professor of microbiology and immunology at UNC. "In the macrophage, this cell death, called pyroptosis, expels the bacterium from the cell, exposing it to other immune defense mechanisms."

A report of the research appears online in the journal Science on Thursday January 24, 2013.

Miao, also a member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, says the new findings show that having this detection pathway protects mice from lethal infection with the type of vacuole-escaping Burkholderia species: B. thailandensis and B. pseudomallei.

Both are close relatives. But they differ in lethality. B. pseudomallei is potentially a biological weapon. Used in a spray, it could potentially infect people via aerosol route, causing sickness and death. Moreover, it also could fall into a latent phase, "essentially turning into a 'sleeper' inside the lungs and hiding there for decades," Miao explains. In contrast, B. thailandensis, which shares many properties with its species counterpart, is not normally able to cause any disease or infection

These environmental bacteria are ubiquitous throughout S.E. Asia, and were it not for the caspase-11 pathway defense system, that part of the world could be uninhabitable, Miao points out.

This grim possibility clearly emerged in the study. Mice that lack the caspase-11 detection pathway succumb to infection not only by B. pseudomallei, but also to the normally benign B. thailandensis. "Thus caspase-11 is critical for surviving exposure to ubiquitous environmental pathogens," the authors conclude.

Miao points to research elsewhere showing that the pathway's abnormal activation in people with septic shock, overwhelming bacterial infection of the blood, is associated with death. "We discovered what the pathway is supposed to do, which may help find ways to tone it down in people with that critical condition.

As to bioterrorism, the researcher says it may be possible to use certain drugs already on the market that safely induce the caspase-11 pathway. "Since this pathway requires pre-stimulation with interferon cytokines, it is conceivable that pre-treating people with interferon drugs could ameliorate a bioterror incident. This could be quite important in the case of Burkholderia, since these bacteria are naturally resistant to numerous antibiotics.

"But first we have to find out if they would work in animal models, and consider the logistics of interferon stockpiling, which are currently cost prohibitive."

INFORMATION:

UNC co-authors are Youssef Aachoui, Jon A. Hagar, Peggy A. Cotter and Christine G. Campos. Alan Aderem, Irina A. Leaf, Daniel E. Zak are from Seattle Biomedical Research Institute, Seattle, WA. Russell E. Vance, Mary F. Fontana and Michael Tan are from the department of molecular and cell biology, University of California at Berkeley.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI097518 (E.A.M.) and AI057141 (E.A.M. and A.A.), AI065359 (P.A.C.), AI075039 (R.E.V.), AI080749 (R.E.V.), and AI063302 (R.E.V.) Investigator Awards from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and Cancer Research Institute (R.E.V.), and an NSF graduate fellowship (M.F.F.).

Immune cell suicide alarm helps destroy escaping bacteria

2013-01-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Out-of-pocket costs for breast cancer probably manageable for most Canadian women

2013-01-25

Out-of-pocket costs resulting from breast cancer care in the year following diagnosis are likely manageable for most women, but some women are at a higher risk of experiencing the financial burden that comes from those costs in Canadian breast cancer patients, according to a study published January 24 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

While extensive information about the level of out-of-pocket costs after early breast cancer diagnosis has been unavailable until now, the costs resulting from the disease and the effects the costs have on family financial ...

Fruit and vegetable intake is associated with lower risk of ER- breast cancer

2013-01-25

There is no association between total fruit and vegetable intake and risk of overall breast cancer, but vegetable consumption is associated with a lower risk of estrogen receptor-negative (ER-) breast cancer, according to a study published January 24 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The intake of fruits and vegetables has been hypothesized to lower breast cancer risk, however the existing evidence is inconclusive. There are many subtypes of breast cancer including ER- and ER positive (ER+) tumors and each may have distinct etiologies. Since ER- tumors, ...

Spotting fetal growth problems early could cut UK stillbirths by 600 a year

2013-01-25

The authors say spotting it early could substantially reduce the risk, and this needs to become a cornerstone of safety and effectiveness in antenatal care.

Stillbirth rates in the United Kingdom are among the highest in developed countries. They have often been considered unexplained and unavoidable, and their rates have changed little over the last two decades.

Recently, doctors have found that many stillborn babies fail to reach their growth potential, prompting a renewed focus on what causes fetal growth restriction. So a team of researchers at the West Midlands ...

Scientists discover how epigenetic information could be inherited

2013-01-25

New research reveals a potential way for how parents' experiences could be passed to their offspring's genes. The research was published today, 25 January, in the journal Science.

Epigenetics is a system that turns our genes on and off. The process works by chemical tags, known as epigenetic marks, attaching to DNA and telling a cell to either use or ignore a particular gene.

The most common epigenetic mark is a methyl group. When these groups fasten to DNA through a process called methylation they block the attachment of proteins which normally turn the genes on. ...

Researchers discover new mutations driving malignant melanoma

2013-01-25

BOSTON—Two new mutations that collectively occur in 71 percent of malignant melanoma tumors have been discovered in what scientists call the "dark matter" of the cancer genome, where cancer-related mutations haven't been previously found.

Reporting their findings in the Jan. 24 issue of Science Express, the researchers from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Broad Institute said the highly "recurrent" mutations – occurring in the tumors of many people – may be the most common mutations in melanoma cells found to date.

The researchers said these cancer-associated ...

Red explosions: The secret life of binary stars is revealed

2013-01-25

(Edmonton) A University of Alberta professor has revealed the workings of a celestial event involving binary stars that results in an explosion so powerful it ranks close to Supernovae in luminosity.

Astrophysicists have long debated about what happens when binary stars, two stars that orbit one another, come together in a common envelope.

When this dramatic cannibalizing event ends there are two possible outcomes; the two stars merge into a single star or an initial binary transforms in an exotic short-period one.

The event is believed to take anywhere from a dozen ...

Gene sequencing project mines data once considered 'junk' for clues about cancer

2013-01-25

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – January 24, 2013) Genome sequencing data once regarded as junk is now being used to gain important clues to help understand disease. The latest example comes from the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital – Washington University Pediatric Cancer Genome Project, where scientists have developed an approach to mine the repetitive segments of DNA at the ends of chromosomes for insights into cancer.

These segments, known as telomeres, had previously been ignored in next-generation sequencing efforts. That is because their repetitive nature meant that the ...

Newly discovered 'scarecrow' gene might trigger big boost in food production

2013-01-25

ITHACA, N.Y. – With projections of 9.5 billion people by 2050, humanity faces the challenge of feeding modern diets to additional mouths while using the same amounts of water, fertilizer and arable land as today.

Cornell University researchers have taken a leap toward meeting those needs by discovering a gene that could lead to new varieties of staple crops with 50 percent higher yields.

The gene, called Scarecrow, is the first discovered to control a special leaf structure, known as Kranz anatomy, which leads to more efficient photosynthesis. Plants photosynthesize ...

The storm that never was: Why the weatherman is often wrong

2013-01-25

Have you ever woken up to a sunny forecast only to get soaked on your way to the office? On days like that it's easy to blame the weatherman.

But BYU mechanical engineering professor Julie Crockett doesn't get mad at meteorologists. She understands something that very few people know: it's not the weatherman's fault he's wrong so often.

According to Crockett, forecasters make mistakes because the models they use for predicting weather can't accurately track highly influential elements called internal waves.

Atmospheric internal waves are waves that propagate between ...

Prenatal inflammation linked to autism risk

2013-01-25

Maternal inflammation during early pregnancy may be related to an increased risk of autism in children, according to new findings supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), part of the National Institutes of Health. Researchers found this in children of mothers with elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), a well-established marker of systemic inflammation.

The risk of autism among children in the study was increased by 43 percent among mothers with CRP levels in the top 20th percentile, and by 80 percent for maternal CRP in the top 10th ...