(Press-News.org)

VIDEO:

Diabetes drug could hold promise for lung cancer patients.

Click here for more information.

LA JOLLA, CA— Ever since discovering a decade ago that a gene altered in lung cancer regulated an enzyme used in therapies against diabetes, Reuben Shaw has wondered if drugs originally designed to treat metabolic diseases could also work against cancer.

The growing evidence that cancer and metabolism are connected, emerging from a number of laboratories around the world over the past 10 years, has further fueled these hopes, though scientists are still working to identify what tumors might be most responsive and which drugs most useful.

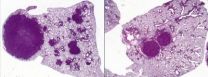

Now, in a new study in the journal Cancer Cell, Shaw and a team of scientists at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies found that phenformin, a derivative of the widely-used diabetes drug metformin, decreased the size of lung tumors in mice and increased the animals' survival. The findings may give hope to the nearly 30 percent of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) whose tumors lack LKB1 (also called STK11).

The LKB1 gene turns on a metabolic enzyme called AMPK when energy levels of ATP, molecules that store the energy we need for just about everything we do, run low in cells. In a previous study, Shaw, an associate professor in Salk's Molecular and Cell Biology Laboratory and researcher in the Institute's new Helmsley Center for Genomic Medicine, demonstrated that cells lacking a normal copy of the LKB1 gene fail to activate AMPK in response to low energy levels. LKB1-dependent activation of AMPK serves as a low-energy checkpoint in the cell. Cells that lack LKB1 are unable to sense such metabolic stress and initiate the process to restore their ATP levels following a metabolic change. As a result, these LKB1-mutant cells run out of cellular energy and undergo apoptosis, or programmed cell death, whereas cells with intact LKB1 are alerted to the crisis and re-correct their metabolism.

"The driving idea behind the research is knowing that AMPK serves as a sensor for low energy loss in cells and that LKB1-deficient cells lack the ability to activate AMPK and sense energy loss," says David Shackelford, a postdoctoral researcher at Salk who spearheaded the study in Shaw's lab and is now an assistant professor at UCLA's David Geffen School of Medicine.

That led Shaw and his team to a class of drugs called biguanides, which lower cellular energy levels by attacking the power stations of the cell, called mitochondria. Metformin and phenformin both inhibit mitochondria; however, phenformin is nearly 50 times as potent as metformin. In the study, the researchers tested phenformin as a chemotherapy agent in genetically-engineered mice lacking LKB1 and which had advanced stage lung tumors. After three weeks of treatment, Shaw and his team saw a modest reduction in tumor burden in the mice.

Continuing the study between Salk and UCLA, Shaw and Shackelford coordinated teams in both locations to perform further testing on mice with earlier stage disease, using cutting-edge imaging technologies just like those used on lung cancer patients in the clinic. They found that early phenformin treatment causes increased survival and slower tumor progression in tumors lacking LKB1, but had no significant benefit for tumors with alterations in other lung cancer genes. This specificity in treatment fits with an emerging approach in cancer treatment nationwide, known as personalized medicine, in which the therapies for each patient are selected based on the genes altered in their tumors.

"This study is a proof-of-principle that drugs of this chemical type cause energy stress and lower ATP levels to where it kills LKB1-deficient cells without damaging normal, healthy cells," says Shaw, senior author of the study.

The Food and Drug Administration took phenformin off the market in 1978 due to a high risk of lactic acid buildup in patients with compromised kidney function, which is not uncommon among diabetics but less of an issue for most cancer patients. The issue of kidney toxicity would also be bypassed in cancer patients because the course of treatment is much shorter, measured in weeks to months compared to years of treatment for diabetes patients.

The next step is to determine if phenformin alone would be a sufficient therapy for certain subsets of NSCLC or if the drug would perform better in combination with existing cancer drugs. Based on their findings, the researchers say that phenformin would be most useful in treating early-stage LKB1-mutant NSCLC, as an adjuvant therapy following surgical removal of a tumor, or in combination with other therapeutics for advanced tumors.

"The good news," says Shackelford, "is that our work provides a basis to initiate human studies. If we can organize enough clinicians who believe in investigating phenformin—and many do—then phenformin as an anti-cancer agent could be a reality in the next several years."

INFORMATION:

Other researchers on the study were Laurie Gerken, Debbie S. Vasquez, and Mathias Leblanc of the Salk Institute, and Evan Abt, Atsuko Seki, Liu Wei, Michael C. Fishbein, Johannes Czernin, and Paul S. Mischel, of the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The work was supported by the Salk Institute's Dulbecco Center for Cancer Research, the Adler Family Foundation, the Ahmanson Translational Imaging Division at UCLA, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institutes of Health, the American Cancer Society, the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused on both discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

Diabetes drug could hold promise for lung cancer patients

Salk study suggests metabolism-based cancer therapy may be useful for non-small cell lung cancer

2013-01-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The 'July effect' -- negligible for outcomes following spine surgery

2013-01-29

Charlottesville, VA, January 29, 2013. The "July effect"—the notion that the influx of new residents and fellows at teaching hospitals in July of each year adversely affects patient care and outcomes—was examined in a very large data set of hospitalizations for patients undergoing spine surgery. Researchers at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN) and the University of Virginia Health System (Charlottesville, VA) found a negligible effect on periprocedural outcomes among patients treated by spine surgery. Detailed results of their thorough study are furnished in the article "The ...

Increasing severity of erectile dysfunction is a marker for increasing risk of cardiovascular disease and death

2013-01-29

A large study published in PLOS Medicine on January 29, 2013, shows that the risk of future cardiovascular disease and death increased with severity of erectile dysfunction in men both with and without a history of cardiovascular disease. While previous studies have shown an association between ED and CVD risk, this study finds that the severity of ED corresponds to the increased risk of CVD hospitalization and all-cause mortality.

The study authors, Emily Banks (from the Australian National University) and colleagues, analyzed data from the Australian prospective cohort ...

New evidence highlights threat to Caribbean coral reef growth

2013-01-29

Coral reefs build their structures by both producing and accumulating calcium carbonate, and this is essential for the maintenance and continued vertical growth capacity of reefs. An international research team has discovered that the amount of new carbonate being added by Caribbean coral reefs is now significantly below rates measured over recent geological timescales, and in some habitats is as much as 70% lower.

Coral reefs form some of the planet's most biologically diverse ecosystems, and provide valuable services to humans and wildlife. However, their ability to ...

Could the timing of when you eat, be just as important as what you eat?

2013-01-29

Boston, MA—Most weight-loss plans center around a balance between caloric intake and energy expenditure. However, new research has shed light on a new factor that is necessary to shed pounds: timing. Researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH), in collaboration with the University of Murcia and Tufts University, have found that it's not simply what you eat, but also when you eat, that may help with weight-loss regulation.

The study will be published on January 29, 2013 in the International Journal of Obesity.

"This is the first large-scale prospective study ...

Debunking the 'July effect': Surgery date has little impact on outcome, Mayo Clinic finds

2013-01-29

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- The "July Effect" -- the notion that the influx of new residents and fellows at teaching hospitals each July makes that the worse time of year to be a patient -- seems to be a myth, according to new Mayo Clinic research that examined nearly 1 million hospitalizations for patients undergoing spine surgery from 2001 to 2008. Among those going under the knife, researchers discovered that the month surgery occurred had an insignificant impact on patient outcomes.

In addition, no substantial "July Effect" was observed in higher-risk patients, those admitted ...

Physicians' brain scans indicate doctors can feel their patients' pain -- and their relief

2013-01-29

BOSTON – A patient's relationship with his or her doctor has long been considered an important component of healing. Now, in a novel investigation in which physicians underwent brain scans while they believed they were actually treating patients, researchers have provided the first scientific evidence indicating that doctors truly can feel their patients' pain – and can also experience their relief following treatment.

Led by researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and the Program in Placebo Studies and Therapeutic Encounter (PiPS) at Beth Israel Deaconess ...

Preclinical study identifies 'master' proto-oncogene that regulates ovarian cancer metastasis

2013-01-29

Scientists at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have discovered the signaling pathway whereby a master regulator of cancer cell proteins – known as Src – leads to ovarian cancer progression when exposed to stress hormones. The researchers report in the current issue of Nature Communications that beta blocker drugs mitigate this effect and reduce cancer deaths by an average of 17 percent.

Src (pronounced "sarc," short for sarcoma) is a proto-oncogene – a normal gene that can become an oncogene due to increased expression – involved in the regulation of ...

Medical societies unite on patient-centered measures for nonsurgical stroke interventions

2013-01-29

FAIRFAX, Va.—The first outcome-based guidelines for interventional treatment of acute ischemic stroke—providing recommendations for rapid treatment—will benefit individuals suffering from brain attacks, often caused by artery-blocking blood clots. Representatives from the Society of Interventional Radiology and seven other medical societies created a multispecialty and international consensus on the metrics and benchmarks for processes of care and technical and clinical outcomes for stroke patients.

In February, the guidelines will be published first in SIR's Journal ...

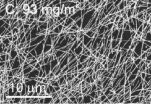

New options for transparent contact electrodes

2013-01-29

This press release is available in German.

Found in flat screens, solar modules, or in new organic light-emitting diode (LED) displays, transparent electrodes have become ubiquitous. Typically, they consist of metal oxides like In2O3, SnO2, ZnO and TiO2.

But since raw materials like indium are becoming more and more costly, researchers have begun to look elsewhere for alternatives. A new review article by HZB scientist Dr. Klaus Ellmer, published in the renowned scientific journal Nature Photonics, is hoping to shed light on the different advantages and disadvantages ...

Epigenetic control of cardiogenesis

2013-01-29

This press release is available in German.

Many different tissues and organs form from pluripotent stem cells during embryonic development. To date it had been known that these processes are controlled by transcription factors for specific tissues. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin, in collaboration with colleagues at MIT and the Broad Institute in Boston, have now been able to demonstrate that RNA molecules, which do not act as templates for protein synthesis, participate in these processes as well. The scientists knocked down ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Diabetes drug could hold promise for lung cancer patientsSalk study suggests metabolism-based cancer therapy may be useful for non-small cell lung cancer