(Press-News.org) PASADENA, Calif.—The skin is a human being's largest sensory organ, helping to distinguish between a pleasant contact, like a caress, and a negative sensation, like a pinch or a burn. Previous studies have shown that these sensations are carried to the brain by different types of sensory neurons that have nerve endings in the skin. Only a few of those neuron types have been identified, however, and most of those detect painful stimuli. Now biologists at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) have identified in mice a specific class of skin sensory neurons that reacts to an apparently pleasurable stimulus.

More specifically, the team, led by David J. Anderson, Seymour Benzer Professor of Biology at Caltech, was able to pinpoint individual neurons that were activated by massage-like stroking of the skin. The team's results are outlined in the January 31 issue of the journal Nature.

"We've known a lot about the neurons that detect things that make us hurt or feel pain, but we've known much less about the identity of the neurons that make us feel good when they are stimulated," says Anderson, who is also an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. "Generally it's a lot easier to study things that are painful because animals have evolved to become much more sensitive to things that hurt or are fearful than to things that feel good. Showing a positive influence of something on an animal model is not that easy."

In fact, the researchers had to develop new methods and technologies to get their results. First, Sophia Vrontou, a postdoctoral fellow in Anderson's lab and the lead author of the study, developed a line of genetically modified mice that had tags, or molecular markers, on the neurons that the team wanted to study. Then she placed a molecule in this specific population of neurons that fluoresced, or lit up, when the neurons were activated.

"The next step was to figure out a way of recording those flashes of light in those neurons in an intact mouse while stroking and poking its body," says Anderson. "We took advantage of the fact that these sensory neurons are bipolar in the sense that they send one branch into the skin that detects stimuli, and another branch into the spinal cord to relay the message detected in the skin to the brain."

The team obtained the needed data by placing the mouse under a special microscope with very high magnification and recording the level of fluorescent light in the fibers of neurons in the spinal cord as the animal was stroked, poked, tickled, and pinched. Through a painstaking process of applying stimuli to one tiny area of the animal's body at a time, they were able to confirm that certain neurons lit up only when stroked. A different class of neurons, by contrast, was activated by poking or pinching the skin, but not by stroking.

"Massage-like stroking is a stimulus that, if were we to experience it, would feel good to us, but as scientists we can't just assume that because something feels good to us, it has to also feel good to an animal," says Anderson. "So we then had to design an experiment to show that artificially activating just these neurons—without actually stroking the mouse—felt good to the mouse."

The researchers did this by creating a box that contained left, right, and center rooms connected by little doors. The left and right rooms were different enough that a mouse could distinguish them through smell, sight, and touch. In the left room, the mouse received an injection of a drug that selectively activated the neurons shown to detect massage-like stroking. In the room on the right, the mouse received a control injection of saline. After a few sessions in each outer room, the animal was placed in the center, with the doors open to see which room it preferred. It clearly favored the room where the massage-sensitive neurons were activated. According to Anderson, this was the first time anyone has used this type of conditioned place-preference experiment to show that activating a specific population of neurons in the skin can actually make an animal experience a pleasurable or rewarding state—in effect, to "feel good."

The team's findings are significant for several reasons, he says. First, the methods that they developed give scientists who have discovered a new kind of neuron a way to find out what activates that neuron in the skin.

"Since there are probably dozens of different kinds of neurons that innervate the skin, we hope this will advance the field by making it possible to figure out all of the different kinds of neurons that detect various types of stimuli," explains Anderson. The second reason the results are important, he says, "is that now that we know these neurons detect massage-like stimuli, the results raise new sets of questions about which molecules in those neurons help the animal detect stroking but not poking."

The other benefit of their new methods, Anderson says, is that they will allow researchers to, in principle, trace the circuitry from those neurons up into the brain to ask why and how activating these neurons makes the animal feel good, whereas activating other neurons that are literally right next to them in the skin makes the animal feel bad.

"We are now most interested in how these neurons communicate to the brain through circuits," says Anderson. "In other words, what part of the circuit in the brain is responsible for the good feeling that is apparently produced by activating these neurons? It may seem frivolous to be identifying massage neurons in a mouse, but it could be that some good might come out of this down the road."

INFORMATION:

Allan M. Wong, a senior research fellow in biology at Caltech, and Kristofer K. Rau and Richard Koerber from the University of Pittsburgh were also coauthors on the Nature paper, "Genetic identification of C fibers that detect massage-like stroking of hairy skin in vivo." Funding for this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the Human Frontiers Science Program, and the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation.

Written by Katie Neith

Sorting out stroking sensations

Caltech biologists find individual neurons in the skin that react to massage

2013-01-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Rejuvenation of the Southern Appalachians

2013-01-31

Boulder, Colorado, USA – In the February 2013 issue of GSA Today, Sean Gallen and his colleagues from the Department of Marine, Earth, and Atmospheric Sciences at North Carolina State University take a new look at the origin of the Miocene rejuvenation of topographic relief in the southern Appalachians.

Conventional wisdom holds that the southern Appalachian Mountains have not experienced a significant phase of tectonic forcing for more than 200 million years; yet, they share many characteristics with tectonically active settings, including locally high topographic relief, ...

Empathy and age

2013-01-31

According to a new study of more than 75,000 adults, women in that age group are more empathic than men of the same age and than younger or older people.

"Overall, late middle-aged adults were higher in both of the aspects of empathy that we measured," says Sara Konrath, co-author of an article on age and empathy forthcoming in the Journals of Gerontology: Psychological and Social Sciences.

"They reported that they were more likely to react emotionally to the experiences of others, and they were also more likely to try to understand how things looked from the perspective ...

UNC scientists unveil a superbug's secret to antibiotic resistance

2013-01-31

Worldwide, many strains of the bacterium Staphyloccocus aureus, commonly known as staph infections, are already resistant to all antibiotics except vancomycin. But as bacteria are becoming resistant to this once powerful antidote, S. aureus has moved one step closer to becoming an unstoppable killer. Now, researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have not only identified the mechanism by which vancomycin resistance spreads from one bacterium to the next, but also have suggested ways to potentially stop the transfer.

The work, led by Matthew Redinbo, ...

Binge drinking increases risk of Type 2 diabetes by causing insulin resistance

2013-01-31

Binge drinking causes insulin resistance, which increases the risk of Type 2 diabetes, according to the results of an animal study led by researchers at the Diabetes Obesity and Metabolism Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The authors further discovered that alcohol disrupts insulin-receptor signaling by causing inflammation in the hypothalamus area of the brain.

The results are published in the January 30 issue of the journal Science Translational Medicine.

"Insulin resistance has emerged as a key metabolic defect leading to Type 2 diabetes ...

Mount Sinai launches clinical trial to treat chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis

2013-01-31

Patients are currently being enrolled in the first clinical trial to investigate the efficacy of immunological therapy for chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis. The trial is being conducted by researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Mount Sinai has the largest Sarcoidosis Service in the world and is one of only two institutions in the country participating in the trial; the other is the University of Cincinnati. Mount Sinai is a National Institutes of Health Center of Excellence for research in sarcoidosis.

"The current standard treatment for chronic pulmonary ...

New semiconductor research may extend integrated circuit battery life tenfold

2013-01-31

Researchers at Rochester Institute of Technology, international semiconductor consortium SEMATECH and Texas State University have demonstrated that use of new methods and materials for building integrated circuits can reduce power—extending battery life to 10 times longer for mobile applications compared to conventional transistors.

The key to the breakthrough is a tunneling field effect transistor. Transistors are switches that control the movement of electrons through material to conduct the electrical currents needed to run circuits. Unlike standard transistors, which ...

Satellite image shows eastern US severe weather system

2013-01-31

A powerful cold front moving from the central United States to the East Coast is wiping out spring-like temperatures and replacing them with winter-time temperatures with powerful storms in between. An image released from NASA using data from NOAA's GOES-13 satellite provides a stunning look at the powerful system that brings a return to winter weather in its wake.

On Jan. 30 at 1825 UTC (1:25 p.m. EST), NOAA's GOES-13 satellite captured an image of clouds associated with the strong cold front. The visible GOES-13 image shows a line of clouds that stretch from Canada ...

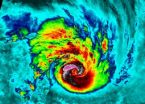

NASA-NOAA's Suomi NPP satellite sees powerful Cyclone Felleng

2013-01-31

False-colored night-time satellite imagery from NASA-NOAA's Suomi NPP satellite clearly shows bands of thunderstorms wrapping into the eye of Cyclone Felleng as it parallels the coast of eastern Madagascar.

The Visible Infrared Imager Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) aboard NASA-NOAA's Suomi NPP satellite captured a night-time image of Cyclone Felleng when it was located east of Madagascar (4:09 p.m. EST/Jan. 30 at 12:09 a.m. local time, Madagascar). The image was created at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and was false colored to reveal temperatures. The image shows powerful ...

Rutgers physics professors find new order in quantum electronic material

2013-01-31

Two Rutgers physics professors have proposed an explanation for a new type of order, or symmetry, in an exotic material made with uranium – a theory that may one day lead to enhanced computer displays and data storage systems and more powerful superconducting magnets for medical imaging and levitating high-speed trains.

Their discovery, published in this week's issue of the journal Nature, has piqued the interest of scientists worldwide. It is one of the rare theory-only papers that this selective publication accepts. Typically the journal's papers describe results of ...

Archaic Native Americans built massive Louisiana mound in less than 90 days

2013-01-31

Nominated early this year for recognition on the UNESCO World Heritage List, which includes such famous cultural sites as the Taj Mahal, Machu Picchu and Stonehenge, the earthen works at Poverty Point, La., have been described as one of the world's greatest feats of construction by an archaic civilization of hunters and gatherers.

Now, new research in the current issue of the journal Geoarchaeology, offers compelling evidence that one of the massive earthen mounds at Poverty Point was constructed in less than 90 days, and perhaps as quickly as 30 days — an incredible ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Bison hunters abandoned long-used site 1,100 years ago to adapt to changing climate

Parents of children with medical complexity report major challenges with at-home medical devices

The nonlinear Hall effect induced by electrochemical intercalation in MoS2 thin flake devices

Moving beyond money to measure the true value of Earth science information

Engineered moths could replace mice in research into “one of the biggest threats to human health”

Can medical AI lie? Large study maps how LLMs handle health misinformation

The Lancet: People with obesity at 70% higher risk of serious infection with one in ten infectious disease deaths globally potentially linked to obesity, study suggests

Obesity linked to one in 10 infection deaths globally

Legalization of cannabis + retail sales linked to rise in its use and co-use of tobacco

Porpoises ‘buzz’ less when boats are nearby

When heat flows backwards: A neat solution for hydrodynamic heat transport

Firearm injury survivors face long-term health challenges

Columbia Engineering announces new program: Master of Science in Artificial Intelligence

Global collaboration launches streamlined-access to Shank3 cKO research model

Can the digital economy save our lungs and the planet?

Researchers use machine learning to design next generation cooling fluids for electronics and energy systems

Scientists propose new framework to track and manage hidden risks of industrial chemicals across their life cycle

Physicians are not providers: New ACP paper says names in health care have ethical significance

Breakthrough University of Cincinnati study sheds light on survival of new neurons in adult brain

UW researchers use satellite data to quantify methane loss in the stratosphere

Climate change could halve areas suitable for cattle, sheep and goat farming by 2100

Building blocks of life discovered in Bennu asteroid rewrite origin story

Engineered immune cells help reduce toxic proteins in the brain

Novel materials design approach achieves a giant cooling effect and excellent durability in magnetic refrigeration materials

PBM markets for Medicare Part D or Medicaid are highly concentrated in nearly every state

Baycrest study reveals how imagery styles shape pathways into STEM and why gender gaps persist

Decades later, brain training lowers dementia risk

Adrienne Sponberg named executive director of the Ecological Society of America

Cells in the ear that may be crucial for balance

Exploring why some children struggle to learn math

[Press-News.org] Sorting out stroking sensationsCaltech biologists find individual neurons in the skin that react to massage