(Press-News.org) When doctors at the University of Iowa prepared a patient to inhale a panic-inducing dose of carbon dioxide, she was fearless. But within seconds of breathing in the mixture, she cried for help, overwhelmed by the sensation that she was suffocating.

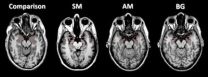

The patient, a woman in her 40s known as SM, has an extremely rare condition called Urbach-Wiethe disease that has caused extensive damage to the amygdala, an almond-shaped area in the brain long known for its role in fear. She had not felt terror since getting the disease when she was an adolescent.

In a paper published online Feb. 3 in the journal Nature Neuroscience, the UI team provides proof that the amygdala is not the only gatekeeper of fear in the human mind. Other regions—such as the brainstem, diencephalon, or insular cortex—could sense the body's most primal inner signals of danger when basic survival is threatened.

"This research says panic, or intense fear, is induced somewhere outside of the amygdala," says John Wemmie, associate professor of psychiatry at the UI and senior author on the paper. "This could be a fundamental part of explaining why people have panic attacks."

If true, the newly discovered pathways could become targets for treating panic attacks, post-traumatic stress syndrome, and other anxiety-related conditions caused by a swirl of internal emotional triggers.

"Our findings can shed light on how a normal response can lead to a disorder, and also on potential treatment mechanisms," says Daniel Tranel, professor of neurology and psychology at the UI and a corresponding author on the paper.

Decades of research have shown the amygdala plays a central role in generating fear in response to external threats. Indeed, UI researchers have worked for years with SM, and noted her absence of fear when she was confronted with snakes, spiders, horror movies, haunted houses, and other external threats, including an incident where she was held up at knife point. But her response to internal threats had never been explored.

The UI team decided to test SM and two other amygdala-damaged patients with a well-known internally generated threat. In this case, they asked the participants, all females, to inhale a gas mixture containing 35 percent carbon dioxide, one of the most commonly used experiments in the laboratory for inducing a brief bout of panic that lasts for about 30 seconds to a minute. The patients took one deep breath of the gas, and quickly had the classic panic-stricken response expected from those without brain damage: They gasped for air, their heart rate shot up, they became distressed, and they tried to rip off their inhalation masks. Afterward, they recounted sensations that to them were completely novel, describing them as "panic."

"They were scared for their lives," says first author Justin Feinstein, a clinical neuropsychologist who earned his doctorate at the UI last year.

Wemmie had looked at how mice responded to fear, publishing a paper in the journal Cell in 2009 showing that the amygdala can directly detect carbon dioxide to produce fear. He expected to find the same pattern with humans.

"We were completely surprised when the patients had a panic attack," says Wemmie, also a faculty member in the Iowa Neuroscience Graduate Program.

By contrast, only three of 12 healthy participants panicked—a rate similar to adults with no history of panic attacks. Notably, none of the three patients with amygdala damage has a history of panic attacks. The higher rate of carbon dioxide-induced panic in the patients suggests that an intact amygdala may normally inhibit panic.

Interestingly, the amygdala-damaged patients had no fear leading up to the test, unlike the healthy participants, many who began sweating and whose heart rates rose just before inhaling the carbon dioxide. That, of course, was consistent with the notion that the amygdala detects danger in the external environment and physiologically prepares the organism to confront the threat.

"Information from the outside world gets filtered through the amygdala in order to generate fear," Feinstein says. "On the other hand, signs of danger arising from inside the body can provoke a very primal form of fear, even in the absence of a functioning amygdala."

INFORMATION:

Contributing authors include Colin Buzza, Robin Follmer, and William Coryell, from the UI Department of Psychiatry; Rene Hurlemann, from the University of Bonn Department of Psychiatry; Nader Dahdaleh, of the UI Department of Neurosurgery; and Michael Welsh, UI professor of internal medicine and molecular physiology and biophysics and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. Buzza and Hurlemann are co-first authors on the paper.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant number: 5P50NS019632-28), the National Institute of Mental Health Research (grant number: 5R01 MH085724), and the Department of Veterans Affairs helped fund the research. Other funders include a Doris Duke Clinical Research Fellowship, a McKnight Neuroscience of Brain Disorders Award, and a Starting Independent Researcher Grant, jointly provided by the Ministry of Innovation, Science, Research, and Technology of the German State of North Rhine-Westphalia and the University of Bonn.

Human brain is divided on fear and panic

New study contends different areas of brain responsible for external versus internal threats

2013-02-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New criteria for automated preschool vision screening

2013-02-04

San Francisco, CA, February 4, 2012 – The Vision Screening Committee of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, the professional organization for pediatric eye care, has revised its guidelines for automated preschool vision screening based on new evidence. The new guidelines are published in the February issue of the Journal of AAPOS.

Approximately 2% of children develop amblyopia, sometimes known as "lazy eye" – a loss of vision in one or both eyes caused by conditions that impair the normal visual input during the period of development of ...

A little tag with a large effect

2013-02-04

February 4, 2013, New York, NY and Oxford, UK – Nearly every cell in the human body carries a copy of the full human genome. So how is it that the cells that detect light in the human eye are so different from those of, say, the beating heart or the spleen?

The answer, of course, is that each type of cell selectively expresses only a unique suite of genes, actively silencing those that are irrelevant to its function. Scientists have long known that one way in which such gene-silencing occurs is by the chemical modification of cytosine—one of the four bases of DNA that ...

Shop King Jewelers 2013 Valentine's Day Jewelry Sale for Savings on Unique Valentine's Gifts & Valentine's Day Presents for Men and Women

2013-02-04

Searching for the perfect Valentine's Day gift doesn't have to be a stressful experience. King Jewelers believes that the pursuit of a unique valentine's gift for the one you love can be an enjoyable and extremely personal experience, even online. That's why for this Valentine's Day King Jewelers has put together an exclusive selection of fine jewelry, watches, diamond studs, diamond pendants and accessories for men and women that will make ideal Valentine's Day gift ideas for your loved one.

Valentines Day Gift Ideas for Him and Her

Online shoppers will find a wide ...

DNA reveals mating patterns of critically endangered sea turtle

2013-02-04

New University of East Anglia research into the mating habits of a critically endangered sea turtle will help conservationists understand more about its mating patterns.

Research published today in Molecular Ecology shows that female hawksbill turtles mate at the beginning of the season and store sperm for up to 75 days to use when laying multiple nests on the beach.

It also reveals that these turtles are mainly monogamous and don't tend to re-mate during the season.

Because the turtles live underwater, and often far out to sea, little has been understood about their ...

Changes to DNA on-off switches affect cells' ability to repair breaks, respond to chemotherapy

2013-02-04

PHILADELPHIA - Double-strand breaks in DNA happen every time a cell divides and replicates. Depending on the type of cell, that can be pretty often. Many proteins are involved in everyday DNA repair, but if they are mutated, the repair system breaks down and cancer can occur. Cells have two complicated ways to repair these breaks, which can affect the stability of the entire genome.

Roger A. Greenberg, M.D., Ph.D., associate investigator, Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute and associate professor of Cancer Biology at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of ...

Researchers discover mutations linked to relapse of childhood leukemia

2013-02-04

After an intensive three-year hunt through the genome, medical researchers have pinpointed mutations that leads to drug resistance and relapse in the most common type of childhood cancer—the first time anyone has linked the disease's reemergence to specific genetic anomalies.

The discovery, co-lead by William L. Carroll, MD, director of NYU Langone Medical Center's Cancer Institute, is reported in a study published online February 3, 2013, in Nature Genetics.

"There has been no progress in curing children who relapse, in spite of giving them very high doses of chemotherapy ...

Pioneering research helps to unravel the brain's vision secrets

2013-02-04

A new study led by scientists at the Universities of York and Bradford has identified the two areas of the brain responsible for our perception of orientation and shape.

Using sophisticated imaging equipment at York Neuroimaging Centre (YNiC), the research found that the two neighbouring areas of the cortex -- each about the size of a 5p coin and known as human visual field maps -- process the different types of visual information independently.

The scientists, from the Department of Psychology at York and the Bradford School of Optometry & Vision Science established ...

Immune cell 'survival' gene key to better myeloma treatments

2013-02-04

Scientists have identified the gene essential for survival of antibody-producing cells, a finding that could lead to better treatments for diseases where these cells are out of control, such as myeloma and chronic immune disorders.

The discovery that a gene called Mcl-1 is critical for keeping this vital immune cell population alive was made by researchers at Melbourne's Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. Associate Professor David Tarlinton, Dr Victor Peperzak and Dr Ingela Vikstrom from the institute's Immunology division led the research, which was published today in ...

Growth factor aids stem cell regeneration after radiation damage

2013-02-04

DURHAM, N.C. – Epidermal growth factor has been found to speed the recovery of blood-making stem cells after exposure to radiation, according to Duke Medicine researchers. The finding could open new options for treating cancer patients and victims of dirty bombs or nuclear disasters.

Reported in the Feb. 3, 2013, issue of the journal Nature Medicine, the researchers explored what had first appeared to be an anomaly among certain genetically modified mice with an abundance of epidermal growth factor in their bone marrow. The mice were protected from radiation damage, and ...

Recreating natural complex gene regulation

2013-02-04

DURHAM, N.C. – By reproducing in the laboratory the complex interactions that cause human genes to turn on inside cells, Duke University bioengineers have created a system they believe can benefit gene therapy research and the burgeoning field of synthetic biology.

This new approach should help basic scientists as they tease out the effects of "turning on" or "turning off" many different genes, as well as clinicians seeking to develop new gene-based therapies for human disease.

"We know that human genes are not just turned on or off, but can be activated to any level ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Power in motion: transforming energy harvesting with gyroscopes

Ketamine high NOT related to treatment success for people with alcohol problems, study finds

1 in 6 Medicare beneficiaries depend on telehealth for key medical care

Maps can encourage home radon testing in the right settings

Exploring the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline

Machine learning tool can predict serious transplant complications months earlier

Prevalence of over-the-counter and prescription medication use in the US

US child mental health care need, unmet needs, and difficulty accessing services

Incidental rotator cuff abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging

Sensing local fibers in pancreatic tumors, cancer cells ‘choose’ to either grow or tolerate treatment

Barriers to mental health care leave many children behind, new data cautions

Cancer and inflammation: immunologic interplay, translational advances, and clinical strategies

Bioactive polyphenolic compounds and in vitro anti-degenerative property-based pharmacological propensities of some promising germplasms of Amaranthus hypochondriacus L.

AI-powered companionship: PolyU interfaculty scholar harnesses music and empathetic speech in robots to combat loneliness

Antarctica sits above Earth’s strongest “gravity hole.” Now we know how it got that way

Haircare products made with botanicals protects strands, adds shine

Enhanced pulmonary nodule detection and classification using artificial intelligence on LIDC-IDRI data

Using NBA, study finds that pay differences among top performers can erode cooperation

Korea University, Stanford University, and IESGA launch Water Sustainability Index to combat ESG greenwashing

Molecular glue discovery: large scale instead of lucky strike

Insulin resistance predictor highlights cancer connection

Explaining next-generation solar cells

Slippery ions create a smoother path to blue energy

Magnetic resonance imaging opens the door to better treatments for underdiagnosed atypical Parkinsonisms

National poll finds gaps in community preparedness for teen cardiac emergencies

One strategy to block both drug-resistant bacteria and influenza: new broad-spectrum infection prevention approach validated

Survey: 3 in 4 skip physical therapy homework, stunting progress

College students who spend hours on social media are more likely to be lonely – national US study

Evidence behind intermittent fasting for weight loss fails to match hype

How AI tools like DeepSeek are transforming emotional and mental health care of Chinese youth

[Press-News.org] Human brain is divided on fear and panicNew study contends different areas of brain responsible for external versus internal threats