(Press-News.org) ST. LOUIS – In research published in the Jan. 24 edition of PLOS Pathogens, Saint Louis University investigators together with collaborators from the University of Missouri and the University of Pittsburgh report a breakthrough in the pursuit of new hepatitis B drugs that could help cure the virus. Researchers were able to measure and then block a previously unstudied enzyme to stop the virus from replicating, taking advantage of known similarities with another major pathogen, HIV.

John Tavis, Ph.D., study author and professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at SLU, says the finding may lead to drugs which, in combination with existing medications, could suppress the virus far enough to cure patients.

"Hepatitis B is the major cause of liver failure and liver cancer worldwide," Tavis said. "This would have an extremely positive effect on liver disease and liver cancer rates.

"If we can cure hepatitis B, we can eliminate the majority of liver cancer cases. This research is a step toward achieving that goal."

World health experts estimate that more than 350 million people are chronically infected with the hepatitis B virus. Several drugs are able to treat symptoms successfully, though they are not able to cure many patients. Of those infected with hepatitis B virus, up to 1.2 million die from liver failure and liver cancer each year.

A person who is infected with hepatitis B virus can have up to a billion viral copies per drop of blood. To cure a patient, a drug needs to reduce those levels to zero.

Not Quite a Cure

While existing medications are very powerful, they cannot quite deliver the knockout punch to hepatitis B. The drugs approved to treat the virus can reduce its numbers, make symptoms disappear for years and push it to the brink of extinction. But for most people, the medications can't kill the virus completely. And, as long as any virus remains, it can multiply and grow strong again.

And so, hepatitis B treatment usually spans decades, with costs of $400 to $600 a month, if patients can afford the medication. Expensive and beyond the means of many, some patients do not receive any treatment at all. As a compromise measure, some patients opt to take medication for a short time, staving off the damage the illness will cause for a few years.

A 19-Year Puzzle

Hepatitis B virus puts up a protracted fight in the lab, as well. For 19 years, Tavis has worked on a particular part of the virus's genetic puzzle, and until recently he had been, in his words, failing miserably.

The problem was a common one in the laboratory. Until scientists can measure a puzzle piece, they can't study it. And, until researchers have some small success, they don't know if they're on the right track or headed down a dead end.

This was the case for the particular enzyme Tavis believed held answers. Stumped, he returned to the puzzle again and again over the years.

"Until you see that first glimmer, all negatives look the same," Tavis said. "One of the biggest skills in this job is knowing when to give up. It's not obvious when you are wasting time and when you are giving up too early."

In Tavis's case, his instinct served him well, and two years ago, he saw the first glimmer of the answer he was searching for.

A Virus's Tactics

"Viruses are genomic suitcases," Tavis said. "They have many tactics for invading and taking over our cells, using their own DNA as the blueprints."

In the case of hepatitis B virus, and, -- in what turned out to be a lucky break, HIV, as well -- the virus replicates by reverse transcription. In this process, viral DNA is converted to RNA and then converted back to DNA by two viral enzymes, both of which are vital to the virus's replication.

The first of these enzymes, a DNA polymerase, has been well studied in the lab. The five most commonly used hepatitis B drugs are able to treat (but not cure) the illness by blocking this enzyme.

The second enzyme, ribonuclease H (RNAseH) had eluded investigators in the lab. With no means to measure it, researchers hit dead ends even though they believed the enzyme was a promising target, in theory.

So, with five approved drugs targeting the first enzyme and none aimed at the second, Tavis sparred with RNAseH for nearly two decades.

Search for an Assay

Tavis was searching for a yardstick, of sorts.

Though it made sense to target RNAseH, no method existed that allowed researchers to measure the enzyme's activity. Tavis was looking for an assay, a way to tell if a substance would block the enyzme's function.

After years of work, Tavis and his research team saw the first glimmer of activity and were able to develop an assay for RNAseH, allowing him to begin to study the enzyme and try out promising theories about how to block it.

Borrowing from HIV

Because the hepatitis B and HIV viruses both use reverse transcription, the mechanism by which they copy themselves in the body's cells, hepatitis B researchers have been able to benefit from advances in HIV research. Thanks to substantial funding, HIV research has made rapid progress since the virus's discovery. Several effective drugs for HIV treatment work by targeting the reverse transcription process also work against hepatitis B virus.

Though the viruses are quite different, Tavis and his colleagues Stefan Sarafianos, Ph.D. at the University of Missouri and Michael Parniak, Ph.D., at the University of Pittsberg believed that the shared process suggested there should be some chemical similarities that could be exploited.

"Just as every car has tires and an engine, both of these viruses have pieces that serve similar functions. You can take an engine from one car and try it in the other. It might not be a perfect fit, but it should serve the same function."

Once the assay for the RNAseH was developed, Tavis and his team were able to try out this theory.

"We found that what worked with the first enzyme worked with the second enzyme," Tavis said. "This is a proof of principle. We're on the right track."

Tavis now has a measuring tool and evidence that a number of the techniques that stopped HIV, including inhibitors of HIV RNAseH, could also inhibit the hepatitis B virus RNAseH, showing that the parallels held true. From there, Tavis and his team went on to prove that hepatitis B replication could in fact be stopped in cells with drugs that targeted the elusive second enzyme, RNAseH.

Hope on the Horizon

With these promising advances, researchers say that the search for anti-hepatitis B RNAseH drugs is now feasible and that using similar anti-HIV compounds as a guide is likely to have a high chance of success.

The research team's next step will be to study several variations of hepatitis B virus, different genotypes of the virus, to be able to measure and study the RNAseH enzyme in all forms of the virus. Current findings demonstrated success in only some genotypes. Findings from the current study suggest some promising avenues as researchers will now attempt to block RNAseH in the two most common genotypes, B and C.

In addition, researchers will aim to improve the strength and speed of the RNAseH assay for high throughput screening, a process for rapidly screening many thousands of compounds. These developments will clear the way for full-scale antiviral drug discovery.

Investigators have reason to hope that combining a new anti-hepatitis B RNAseH drug with the existing drugs may suppress the virus far enough to cure patients with hepatitis B.

"I anticipate a new drug targeting the second enzyme would be used together with the existing drugs," Tavis said. "They jam different parts of the process.

"The drugs we have are very good drugs. They push the virus down, but they can't quite kill it. They'll still do the heavy lifting in the future, but with an additional drug I hope we'll be able to mop up the rest. Together, they may be able to do it. We don't have a big distance we need to travel to reach that point."

###

Tavis's research was funded by Saint Louis University's President's Research Fund, Friends of the Saint Louis University Liver Center, and the Saint Louis University Cancer Center.

TAKE-AWAYS:

Current hepatitis B drugs can treat but not cure the infection for most people. Saint Louis University researchers' new breakthrough paves the way for additional drugs that can help cure those who are infected.

Researchers were able to measure and then block a previously unstudied enzyme to stop the virus from replicating, taking advantage of known similarities with another major pathogen, HIV.

The search for anti-hepatitis B virus RNAseH drugs is now feasible. Using similar anti-HIV compounds is likely to have a high chance of success.

Because the majority of liver cancer cases worldwide are caused by hepatitis B virus, a cure would dramatically cut liver cancer rates.

As with all laboratory research, more study is needed before a treatment can be approved for patients. In addition to further laboratory research, any new drugs would have to be studied in a clinical trial to know how safe and effective they will be.

Established in 1836, Saint Louis University School of Medicine has the distinction of awarding the first medical degree west of the Mississippi River. The school educates physicians and biomedical scientists, conducts medical research, and provides health care on a local, national and international level. Research at the school seeks new cures and treatments in five key areas: cancer, liver disease, heart/lung disease, aging and brain disease, and infectious disease. END

In a fight to the finish, Saint Louis University research aims knockout punch at hepatitis B

A cure for the virus would reduce liver cancer worldwide

2013-02-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

University of Leicester announces discovery of King Richard III

2013-02-04

UNIVERSITY OF LEICESTER REVEALS:

Wealth of evidence, including radiocarbon dating, radiological evidence, DNA and bone analysis and archaeological results, confirms identity of last Plantagenet king who died over 500 years ago

DNA from skeleton matches TWO of Richard III's maternal line relatives. Leicester genealogist verifies living relatives of Richard III's family

Individual likely to have been killed by one of two fatal injuries to the skull – one possibly from a sword and one possibly from a halberd

10 wounds discovered on skeleton - Richard III killed ...

Human brain is divided on fear and panic

2013-02-04

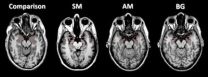

When doctors at the University of Iowa prepared a patient to inhale a panic-inducing dose of carbon dioxide, she was fearless. But within seconds of breathing in the mixture, she cried for help, overwhelmed by the sensation that she was suffocating.

The patient, a woman in her 40s known as SM, has an extremely rare condition called Urbach-Wiethe disease that has caused extensive damage to the amygdala, an almond-shaped area in the brain long known for its role in fear. She had not felt terror since getting the disease when she was an adolescent.

In a paper published ...

New criteria for automated preschool vision screening

2013-02-04

San Francisco, CA, February 4, 2012 – The Vision Screening Committee of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, the professional organization for pediatric eye care, has revised its guidelines for automated preschool vision screening based on new evidence. The new guidelines are published in the February issue of the Journal of AAPOS.

Approximately 2% of children develop amblyopia, sometimes known as "lazy eye" – a loss of vision in one or both eyes caused by conditions that impair the normal visual input during the period of development of ...

A little tag with a large effect

2013-02-04

February 4, 2013, New York, NY and Oxford, UK – Nearly every cell in the human body carries a copy of the full human genome. So how is it that the cells that detect light in the human eye are so different from those of, say, the beating heart or the spleen?

The answer, of course, is that each type of cell selectively expresses only a unique suite of genes, actively silencing those that are irrelevant to its function. Scientists have long known that one way in which such gene-silencing occurs is by the chemical modification of cytosine—one of the four bases of DNA that ...

Shop King Jewelers 2013 Valentine's Day Jewelry Sale for Savings on Unique Valentine's Gifts & Valentine's Day Presents for Men and Women

2013-02-04

Searching for the perfect Valentine's Day gift doesn't have to be a stressful experience. King Jewelers believes that the pursuit of a unique valentine's gift for the one you love can be an enjoyable and extremely personal experience, even online. That's why for this Valentine's Day King Jewelers has put together an exclusive selection of fine jewelry, watches, diamond studs, diamond pendants and accessories for men and women that will make ideal Valentine's Day gift ideas for your loved one.

Valentines Day Gift Ideas for Him and Her

Online shoppers will find a wide ...

DNA reveals mating patterns of critically endangered sea turtle

2013-02-04

New University of East Anglia research into the mating habits of a critically endangered sea turtle will help conservationists understand more about its mating patterns.

Research published today in Molecular Ecology shows that female hawksbill turtles mate at the beginning of the season and store sperm for up to 75 days to use when laying multiple nests on the beach.

It also reveals that these turtles are mainly monogamous and don't tend to re-mate during the season.

Because the turtles live underwater, and often far out to sea, little has been understood about their ...

Changes to DNA on-off switches affect cells' ability to repair breaks, respond to chemotherapy

2013-02-04

PHILADELPHIA - Double-strand breaks in DNA happen every time a cell divides and replicates. Depending on the type of cell, that can be pretty often. Many proteins are involved in everyday DNA repair, but if they are mutated, the repair system breaks down and cancer can occur. Cells have two complicated ways to repair these breaks, which can affect the stability of the entire genome.

Roger A. Greenberg, M.D., Ph.D., associate investigator, Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute and associate professor of Cancer Biology at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of ...

Researchers discover mutations linked to relapse of childhood leukemia

2013-02-04

After an intensive three-year hunt through the genome, medical researchers have pinpointed mutations that leads to drug resistance and relapse in the most common type of childhood cancer—the first time anyone has linked the disease's reemergence to specific genetic anomalies.

The discovery, co-lead by William L. Carroll, MD, director of NYU Langone Medical Center's Cancer Institute, is reported in a study published online February 3, 2013, in Nature Genetics.

"There has been no progress in curing children who relapse, in spite of giving them very high doses of chemotherapy ...

Pioneering research helps to unravel the brain's vision secrets

2013-02-04

A new study led by scientists at the Universities of York and Bradford has identified the two areas of the brain responsible for our perception of orientation and shape.

Using sophisticated imaging equipment at York Neuroimaging Centre (YNiC), the research found that the two neighbouring areas of the cortex -- each about the size of a 5p coin and known as human visual field maps -- process the different types of visual information independently.

The scientists, from the Department of Psychology at York and the Bradford School of Optometry & Vision Science established ...

Immune cell 'survival' gene key to better myeloma treatments

2013-02-04

Scientists have identified the gene essential for survival of antibody-producing cells, a finding that could lead to better treatments for diseases where these cells are out of control, such as myeloma and chronic immune disorders.

The discovery that a gene called Mcl-1 is critical for keeping this vital immune cell population alive was made by researchers at Melbourne's Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. Associate Professor David Tarlinton, Dr Victor Peperzak and Dr Ingela Vikstrom from the institute's Immunology division led the research, which was published today in ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

PhD student maps mysterious upper atmosphere of Uranus for the first time

Idaho National Laboratory to accelerate nuclear energy deployment with NVIDIA AI through the Genesis Mission

Blood test could help guide treatment decisions in germ cell tumors

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

“Cyborg” pancreatic organoids can monitor the maturation of islet cells

Technique to extract concepts from AI models can help steer and monitor model outputs

Study clarifies the cancer genome in domestic cats

Crested Spinosaurus fossil was aquatic, but lived 1,000 kilometers from the Tethys Sea

MULTI-evolve: Rapid evolution of complex multi-mutant proteins

A new method to steer AI output uncovers vulnerabilities and potential improvements

Why some objects in space look like snowmen

Flickering glacial climate may have shaped early human evolution

First AHA/ACC acute pulmonary embolism guideline: prompt diagnosis and treatment are key

Could “cyborg” transplants replace pancreatic tissue damaged by diabetes?

Hearing a molecule’s solo performance

Justice after trauma? Race, red tape keep sexual assault victims from compensation

Columbia researchers awarded ARPA-H funding to speed diagnosis of lymphatic disorders

James R. Downing, MD, to step down as president and CEO of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in late 2026

A remote-controlled CAR-T for safer immunotherapy

UT College of Veterinary Medicine dean elected Fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology

AERA selects 34 exemplary scholars as 2026 Fellows

Similar kinases play distinct roles in the brain

New research takes first step toward advance warnings of space weather

Scientists unlock a massive new ‘color palette’ for biomedical research by synthesizing non-natural amino acids

Brain cells drive endurance gains after exercise

Same-day hospital discharge is safe in selected patients after TAVI

Why do people living at high altitudes have better glucose control? The answer was in plain sight

Red blood cells soak up sugar at high altitude, protecting against diabetes

A new electrolyte points to stronger, safer batteries

Environment: Atmospheric pollution directly linked to rocket re-entry

[Press-News.org] In a fight to the finish, Saint Louis University research aims knockout punch at hepatitis BA cure for the virus would reduce liver cancer worldwide