(Press-News.org) A training regimen to adjust the body's motor reflexes may help improve mobility for some people with incomplete spinal cord injuries, according to a study supported by the National Institutes of Health.

During training, the participants were instructed to suppress a knee jerk-like reflex elicited by a small shock to the leg. Those who were able to calm hyperactive reflexes – a common effect of spinal cord injuries – saw improvements in their walking.

The study was led by Aiko Thompson, Ph.D., and Jonathan Wolpaw, M.D., both of whom hold appointments at the New York state Department of Health and the State University of New York in Albany, and at Columbia University in New York City. The study took place at Helen Hayes Hospital in West Haverstraw, N. Y. It was funded in part by NIH's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), and published in the Journal of Neuroscience.

"People tend to think of reflexes as fixed, but in reality, normal movement requires constant fine tuning of reflexes by the brain. Loss of that fine-tuning is an important part of the disability that comes with a spinal cord injury," said Dr. Wolpaw, a research physician and professor at the Wadsworth Center, the state health department's public health laboratory.

When the brain makes a decision to move, it sends signals that travel through the spinal cord to the appropriate muscles. Spinal reflexes – controlled by local circuits of nerve cells in the spinal cord – provide a way for the body to react and move quickly without a conscious decision from the brain. "They enable you to jerk your hand away from a hot stove before you've registered the pain and experienced severe burns," Dr. Wolpaw said. "The brain can gradually enhance or suppress reflexes as needed," he said.

Some spinal cord injuries involve a complete break and paralysis below the point of injury. More typically, only part of the spinal cord is damaged, leading to less severe disability. After an incomplete injury, some reflexes may be weakened while others become exaggerated. These hyperactive reflexes can cause spasticity (muscle stiffness) and abnormal patterns of muscle use during movement.

The study by Drs. Thompson and Wolpaw involved 13 people who were still able to walk after incomplete spinal cord injuries that had occurred from eight months to 50 years prior to the study. All had spasticity and an impaired ability to walk. The goal was to determine if these individuals could gain mobility by learning to suppress a spinal H-reflex, which is elicited by electrical stimulation rather than by a tendon stretch. H-reflexes are routinely measured for diagnosing nerve disorders and injuries, but this is the first study to examine whether consciously modifying an H-reflex can help people with spinal cord injuries.

Participants in the study received electrical stimulation to the soleus (calf muscle) of their weaker leg while standing with support. The first two weeks of the study involved baseline measurements of the resulting reflex. During the next 10 weeks, nine participants underwent three training sessions per week, during which they viewed the size of their reflexes on a monitor and were encouraged to suppress it. A control group of four participants received the stimulation but no feedback about their reflexes. Before and after these sessions, the researchers measured the participants' walking speed over a distance of 10 meters, and monitored their gait symmetry with electronic shoe implants.

Six of the nine participants in the training group were able to suppress their reflexes. Their walking speed increased by 59 percent on average, and their gait became more symmetrical. These improvements in speed and symmetry were not seen in three participants who were unable to suppress their reflexes, or in the control group. Many participants also spontaneously told the researchers they were noticing improvements in daily living activities. About 85 percent of these comments came from people who were able to control their reflexes after several weeks of training.

Because this was a small study, a larger multi-center trial would be necessary to assess the clinical benefits of the therapy. However, the results are encouraging, said Daofen Chen, Ph.D., a program director at NINDS. "The findings offer hope that reflex conditioning can produce meaningful improvements for some patients with incomplete spinal cord injuries. It is important to realize that this approach rests on a foundation of basic research on the physiology of spinal reflexes," he said.

NINDS has supported Dr. Wolpaw's work on reflex training for nearly three decades. Until recently, this work was done mostly on rats, and focused on reflex control in the uninjured spinal cord. Those studies helped demonstrate that spinal reflexes can change with training, defined many of the complex modifications in brain and spinal cord that underlie reflex change, and established reflex training as a model for studying how circuits in the brain change with learning.

In 2006, Dr. Wolpaw and colleagues reported that reflex training improved mobility for rats with spinal cord injury. He soon brought Dr. Thompson to the Wadsworth Center to design a reflex training protocol for people, and the current study began in 2008. Ferne Pomerantz, M.D., director of spinal cord injury rehabilitation services at Helen Hayes Hospital, was the recruiting physician for the study.

Dr. Wolpaw said he views reflex training, also known as reflex conditioning, as a complement to current rehabilitation practices. The technique could be tailored to focus on specific reflexes that affect different muscle groups, and in some cases, to increase reflexes instead of decrease them. In its 2006 study, his group found that enhancing soleus H-reflex was beneficial for rats that had spinal cord injuries predominantly characterized by weakness without spasticity.

In the current study, it is not clear why only two-thirds of the patients with spinal cord injury were able to suppress their reflexes and benefit from training. However, Dr. Wolpaw has found similar response rates in people and animals without spinal cord injuries.

Dr. Thompson plans to study how durable the effects of training are, but such research presents a design challenge, she said. "Once people noticed their mobility had improved, they started exercising more and getting involved with other types of therapy. Those activities are likely to have additional benefits, and will be difficult to separate from the long-term effects of our reflex conditioning protocol," she said.

INFORMATION:

In addition to grants from NINDS (NS069551, NS022189 and NS061823), this study was funded by the NYS Spinal Cord Injury Research Trust (C023685) and the Helen Hayes Hospital Foundation.

References:

Thompson AK et al. "Operant conditioning of a spinal reflex can improve locomotion after spinal cord injury in humans." Journal of Neuroscience, February 6, 2013.

Chen Y and Chen XY et al. "Operant conditioning of H-reflex can correct a locomotor abnormality after spinal cord injury in rats." Journal of Neuroscience, November 29, 2006.

For more information about spinal cord injury, please visit: http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/sci.

NINDS is the nation's leading funder of research on the brain and nervous system. The NINDS mission is to reduce the burden of neurological disease – a burden borne by every age group, by every segment of society, by people all over the world.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH):

NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit: http://www.nih.gov.

Reflex control could improve walking after incomplete spinal injuries

2013-02-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Obesity leads to vitamin D deficiency

2013-02-06

Obesity can lead to a lack of vitamin D circulating in the body, according to a study led by the UCL Institute of Child Health (ICH). Efforts to tackle obesity should thus also help to reduce levels of vitamin D deficiency in the population, says the lead investigator of the study, Dr Elina Hypponen.

While previous studies have linked vitamin D deficiency with obesity, the ICH-led paper, published in the journal PLOS Medicine, sought to establish the direction of causality i.e. whether a lack of vitamin D triggers a weight gain, or whether obesity leads to the deficiency.

This ...

Tourists face health risks from contact with captive sea turtles

2013-02-06

LA, CA (05 February 2013). Tourists coming into contact with sea turtles at holiday attractions face a risk of health problems, according to research published today by JRSM Short Reports. Encountering free-living sea turtles in nature is quite safe, but contact with wild-caught and captive-housed sea turtles, typically through handling turtles in confined pools or through consuming turtle products, carries the risk of exposure to toxic contaminants and to zoonotic (animal to human) pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. Symptoms, which may take some ...

Insect drives robot to track down smells

2013-02-06

A small, two-wheeled robot has been driven by a male silkmoth to track down the sex pheromone usually given off by a female mate.

The robot has been used to characterise the silkmoth's tracking behaviours and it is hoped that these can be applied to other autonomous robots so they can track down smells, and the subsequent sources, of environmental spills and leaks when fitted with highly sensitive sensors.

The results have been published today, 6 February, in IOP Publishing's journal Bioinspiration and Biomimetics, and include a video of the robot in action http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n2k1T2X7_Aw&feature=youtu.be

The ...

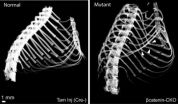

Steroids help reverse rapid bone loss tied to rib fractures

2013-02-06

(Embargoed) CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – New research in animals triggered by a combination of serendipity and counterintuitive thinking could point the way to treating fractures caused by rapid bone loss in people, including patients with metastatic cancers.

A series of studies at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine found that steroid drugs, known for inducing bone loss with prolonged use, actually help suppress a molecule that's key to the rapid bone loss process. A report of the new findings appears online Feb. 5, 2013 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Osteoporosis ...

Paternal obesity impacts child's chances of cancer

2013-02-06

Maternal diet and weight can impact their child's health even before birth – but so can a father's, shows a study published in BioMed Central's open access journal BMC Medicine. Hypomethylation of the gene coding for the Insulin-like growth factor 2, (IGF2),in newborns correlates to an increased risk of developing cancer later in life, and, for babies born to obese fathers, there is a decrease in the amount of DNA methylation of IGF2 in foetal cells isolated from cord blood.

As part of the Newborn Epigenetics Study (NEST) at Duke University Hospital, information was collected ...

The number of multiple births affected by congenital anomalies has doubled since the 1980s

2013-02-06

The number of congenital anomalies, or birth defects arising from multiple births has almost doubled since the 1980s, suggests a new study published today (6 February) in BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

The study investigates how the change in the proportion of multiple births has affected the prevalence of congenital anomalies from multiple births, and the relative risk of congenital anomaly in multiple versus singleton births.

This study, led by the University of Ulster over a 24-year period (1984 – 2007) across 14 European countries ...

Study raises questions about dietary fats and heart disease guidance

2013-02-06

Dietary advice about fats and the risk of heart disease is called into question on bmj.com today as a clinical trial shows that replacing saturated animal fats with omega-6 polyunsaturated vegetable fats is linked to an increased risk of death among patients with heart disease.

The researchers say their findings could have important implications for worldwide dietary recommendations.

Advice to substitute vegetable oils rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) for animal fats rich in saturated fats to help reduce the risk of heart disease has been a cornerstone of ...

Green tea and red wine extracts interrupt Alzheimer's disease pathway in cells

2013-02-06

Natural chemicals found in green tea and red wine may disrupt a key step of the Alzheimer's disease pathway, according to new research from the University of Leeds.

In early-stage laboratory experiments, the researchers identified the process which allows harmful clumps of protein to latch on to brain cells, causing them to die. They were able to interrupt this pathway using the purified extracts of EGCG from green tea and resveratrol from red wine.

The findings, published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, offer potential new targets for developing drugs to treat ...

Obesity in dads may be associated with offspring's increased risk of disease

2013-02-06

DURHAM, N.C. -- A father's obesity is one factor that may influence his children's health and potentially raise their risk for diseases like cancer, according to new research from Duke Medicine.

The study, which appears Feb. 6 in the journal BMC Medicine, is the first in humans to show that paternal obesity may alter a genetic mechanism in the next generation, suggesting that a father's lifestyle factors may be transmitted to his children.

"Understanding the risks of the current Western lifestyle on future generations is important," said molecular biologist Adelheid ...

Purification on the cheap

2013-02-06

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Increased natural gas production is seen as a crucial step away from the greenhouse gas emissions of coal plants and toward U.S. energy independence. But natural gas wells have problems: Large volumes of deep water, often heavily laden with salts and minerals, flow out along with the gas. That so-called "produced water" must be disposed of, or cleaned.

Now, a process developed by engineers at MIT could solve the problem and produce clean water at relatively low cost. After further development, the process could also lead to inexpensive, efficient desalination ...