(Press-News.org) Chapel Hill, NC – Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) hide within the worldwide human population. While dormant in the vast majority of those infected, these active herpesviruses can develop into several forms of cancer. In an effort to understand and eventually develop treatments for these viruses, researchers at the University of North Carolina have identified a family of human genes known as Tousled-like kinases (TLKs) that play a key role in the suppression and activation of these viruses.

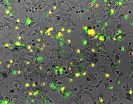

In a paper published by Cell Host and Microbe on Feb. 13, a research team led by Blossom Damania, PhD, of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology and member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, found that suppressing the TLK enzyme causes the activation of the lytic cycle of both EBV and KSHV. During this active phase, these viruses begin to spread and replicate, and become vulnerable to anti-viral treatments.

"When TLK is present, these viruses stay latent, but when it is absent, these viruses can replicate" said Dr. Damania.

Patrick Dillon, a postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Damania's lab, led the study. Other co-authors included UNC Lineberger members Drs. Dirk Dittmer, Nancy Raab-Traub and Gary Johnson.

KSHV and EBV are blood-borne viruses that remain dormant in more than 95 percent of those infected, making treatment of these viruses difficult. Both viruses are associated with a number of different lymphomas, sarcomas, and carcinomas, and many patients with suppressed immune systems are at risk for these virus-associated cancers.

"The dormant state of these viruses is what makes it so hard to treat these infections and the cancers associated with these infections," said Dr. Damania.

Researchers have known that stimuli such as stress can activate the virus from dormancy, but they do not understand the molecular basis of the viral activation cycle. With the discovery of the link between these viruses and TLKs, Dr. Damania said that researchers can begin to look for the molecular actions triggered by events like stress, and how they lead to the suppression of the TLK enzymes.

"What exactly is stress at a molecular level? We don't really understand it fully," said Dr. Damania.

With the discovery that TLKs suppresses these viruses, Dr. Damania said that the proteins can now be investigated as a possible drug target for these virus-associated cancers. In its normal function in the cell, TLKs play a role in the maintenance of the genome, repairing DNA and the assembly of the chromatin, but there is a lot more to learn about the function of the TLKs, said Dr. Damania. One avenue of her lab's future research will investigate how TLKs function in absence of the virus.

"If we prevent this protein from functioning, and we combine this with a drug that inhibits viral replication, then we could have a target to cure the cell of the virus. If the virus isn't there, the viral-associated cancers aren't present," said Dr. Damania.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by NIH grants CA096500, CA163217, and CA019014, and the UNC Lineberger training grant NIH T32CA009156. Dr. Damania is a Leukemia & Lymphoma Foundation Scholar and a Burroughs Wellcome Investigator in Infectious Disease.

UNC researchers discover gene that suppresses herpesviruses

2013-02-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

'A drop of ink on the luminous sky'

2013-02-13

This part of the constellation of Sagittarius (The Archer) is one of the richest star fields in the whole sky -- the Large Sagittarius Star Cloud. The huge number of stars that light up this region dramatically emphasise the blackness of dark clouds like Barnard 86, which appears at the centre of this new picture from the Wide Field Imager, an instrument mounted on the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at ESO's La Silla Observatory in Chile.

This object, a small, isolated dark nebula known as a Bok globule [1], was described as "a drop of ink on the luminous sky" by its discoverer ...

Study suggests infant deaths can be prevented

2013-02-13

(TORONTO, Canada – Feb. 13, 2013) – An international team of tropical medicine researchers have discovered a potential method for preventing low birth weight in babies born to pregnant women who are exposed to malaria. Low birth weight is the leading cause of infant death globally.

The findings of Malaria Impairs Placental Vascular Development, published today online ahead of print in Cell Host & Microbe, showed that the protein C5a and its receptor, C5aR, seem to control the blood vessel development in the mother's placenta. Without adequate blood vessels in the placenta, ...

Carnegie Mellon brain imaging research shows how unconscious processing improves decision-making

2013-02-13

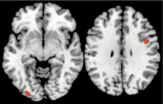

PITTSBURGH—When faced with a difficult decision, it is often suggested to "sleep on it" or take a break from thinking about the decision in order to gain clarity.

But new brain imaging research from Carnegie Mellon University, published in the journal "Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience," finds that the brain regions responsible for making decisions continue to be active even when the conscious brain is distracted with a different task. The research provides some of the first evidence showing how the brain unconsciously processes decision information in ways ...

Study in mice yields Angelman advance

2013-02-13

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In a new study in mice, a scientific collaboration centered at Brown University lays out in unprecedented detail a neurological signaling breakdown in Angelman syndrome, a disorder that affects thousands of children each year, characterized by developmental delay, seizures, and other problems. With the new understanding, the team demonstrated how a synthesized, peptide-like compound called CN2097 works to restore neural functions impaired by the disease.

"I think we are really beginning to understand what's going wrong. That's what's ...

A neural basis for benefits of meditation

2013-02-13

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Why does training in mindfulness meditation help patients manage chronic pain and depression? In a newly published neurophysiological review, Brown University scientists propose that mindfulness practitioners gain enhanced control over sensory cortical alpha rhythms that help regulate how the brain processes and filters sensations, including pain, and memories such as depressive cognitions.

The proposal, based on published experimental results and a validated computer simulation of neural networks, derives its mechanistic framework ...

Wetland trees a significant overlooked source of methane, study finds

2013-02-13

Wetlands are a well-established and prolific source of atmospheric methane. Yet despite an abundance of seething swamps and flooded forests in the tropics, ground-based measurements of methane have fallen well short of the quantities detected in tropical air by satellites.

In 2011, Sunitha Pangala, a PhD student at The Open University, who is co-supervised by University of Bristol researcher Dr Ed Hornibrook, spent several weeks in a forested peat swamp in Borneo with colleague Sam Moore, assessing whether soil methane might be escaping to the atmosphere by an alternative ...

3 'Bigfoot' genomes sequenced in 5-year DNA study

2013-02-13

Dallas, Feb. 13--The multidisciplinary team of scientists, who on November 24, 2012 announced the results of their five-year long study of DNA samples from a novel hominin species, commonly known as "Bigfoot" or "Sasquatch," publishes their peer-reviewed findings today in the DeNovo Journal of Science (http://www.denovojournal.com). The study, which sequenced three whole Sasquatch nuclear genomes, shows that the legendary Sasquatch is extant in North America and is a human relative that arose approximately 13,000 years ago and is hypothesized to be a hybrid cross of modern ...

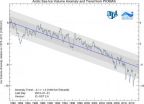

European satellite confirms UW numbers: Arctic Ocean is on thin ice

2013-02-13

The September 2012 record low in Arctic sea-ice extent was big news, but a missing piece of the puzzle was lurking below the ocean's surface. What volume of ice floats on Arctic waters? And how does that compare to previous summers? These are difficult but important questions, because how much ice actually remains suggests how vulnerable the ice pack will be to more warming.

New satellite observations confirm a University of Washington analysis that for the past three years has produced widely quoted estimates of Arctic sea-ice volume. Findings based on observations from ...

We're emotionally distant and that's just fine by me

2013-02-13

When it comes to having a lasting and fulfilling relationship, common wisdom says that feeling close to your romantic partner is paramount. But a new study finds that it's not how close you feel that matters most, it's whether you are as close as you want to be, even if that's really not close at all.

"Our study found that people who yearn for a more intimate partnership and people who crave more distance are equally at risk for having a problematic relationship," says the study's lead author, David M. Frost, PhD, of Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health. ...

Video study shows which fish clean up coral reefs, showing importance of biodiversity

2013-02-13

Using underwater video cameras to record fish feeding on South Pacific coral reefs, scientists have found that herbivorous fish can be picky eaters – a trait that could spell trouble for endangered reef systems.

In a study done at the Fiji Islands, the researchers learned that just four species of herbivorous fish were primarily responsible for removing common and potentially harmful seaweeds on reefs – and that each type of seaweed is eaten by a different fish species. The research demonstrates that particular species, and certain mixes of species, are potentially critical ...