(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Aphasia, an impairment in speaking and understanding language after a stroke, is frustrating both for victims and their loved ones. In two talks Saturday, Feb. 16, 2013, at the conference of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Boston, Sheila Blumstein, the Albert D. Mead Professor of Cognitive, Linguistic, and Psychological Sciences at Brown University, will describe how she has been translating decades of brain science research into a potential therapy for improving speech production in these patients. Blumstein will speak at a news briefing at 10 a.m. and at a symposium at 3 p.m.

About 80,000 people develop aphasia each year in the United States alone. Nearly all of these individuals have difficulty speaking. For example, some patients (nonfluent aphasics) have trouble producing sounds clearly, making it frustrating for them to speak and difficult for them to be understood. Other patients (fluent aphasics) may select the wrong sound in a word or mix up the order of the sounds. In the latter case, "kitchen" can become "chicken." Blumstein's idea is to use guided speech to help people who have suffered stroke-related brain damage to rebuild their neural speech infrastructure.

Blumstein has been studying aphasia and the neural basis of language her whole career. She uses brain imaging, acoustic analysis, and other lab-based techniques to study how the brain maps sound to meaning and meaning to sound.

What Blumstein and other scientists believe is that the brain organizes words into networks, linked both by similarity of meaning and similarity of sound. To say "pear," a speaker will also activate other competing words like "apple" (which competes in meaning) and "bear"(which competes in sound). Despite this competition, normal speakers are able to select the correct word.

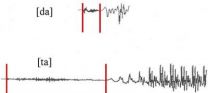

In a study published in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience in 2010, for example, she and her co-authors used functional magnetic resonance imaging to track neural activation patterns in the brains of 18 healthy volunteers as they spoke English words that had similar sounding "competitors" ("cape" and "gape" differ subtly in the first consonant by voicing, i.e. the timing of the onset of vocal cord vibration). Volunteers also spoke words without similar sounding competitors ("cake" has no voiced competitor in English; gake is not a word). What the researchers found is that neural activation within a network of brain regions was modulated differently when subjects said words that had competitors versus words that did not.

One way this competition-mediated difference is apparent in speech production is that words with competitors are produced differently from words that do not have competitors. For example, the voicing of the "t" in "tot" (with a voiced competitor 'dot') is produced with more voicing than the "t" in "top" (there is no 'dop' in English). Through acoustic analysis of the speech of people with aphasia, Blumstein has shown that this difference persists, suggesting that their word networks are still largely intact.

An experimental therapy

The therapy Blumstein has begun testing takes advantage of what she and colleagues have learned about these networks.

"We believe that although the network infrastructure is relatively spared in aphasia, the word representations themselves aren't as strongly activated as they are in normal subjects, leading to speech production impairments," she said. "Our goal is to strengthen these word representations. In doing so it should not only improve production of trained words, but also have a cascading effect and strengthen the representations of words that are part of that word's network."

Much like physical therapy seeks to restore movement by guiding a patient through particularly crucial motions, Blumstein's therapy is designed to restrengthen how the brain accesses its network to produce words by engaging patients in a series of carefully designed utterances.

"We hope to build up the representation of that word and at the same time influence its whole network," she said.

Overall the therapy is designed to last 10 weeks with two sessions a week. In one step of the regimen, a classic technique, a therapist will ask patients to repeat certain training words with a deliberate, melodic intonation. The next session the therapy would repeat those words without the chant-like tone.

"Having to produce words under different speaking conditions shapes and strengthens underlying word representations," said Blumstein, who is affiliated with the Brown Institute for Brain Science.

Confronting the delicate distinctions of words in the network head-on, Blumstein asks patients to say words that sound similar. "Pear" and "Bear" for example. Explicitly saying similar words, Blumstein said, requires that their differences be accentuated, thus helping strengthen the brain's ability to distinguish them.

Finally the therapy builds upon these earlier exercises by encouraging patients to repeat words they have not been practicing. A patient's ability to correctly repeat untrained words is an important test of whether the therapy can generalize to the broader networks of the training words.

In early testing with four patients, two fluent and two nonfluent, Blumstein said she has seen good results. After only two proof-of-concept sessions — one week's worth of training — three of four patients showed improved precision in producing similar sounding trained and untrained words, as measured via computer-assisted acoustic analysis. The patients also produced fewer speaking errors and had to try fewer times to say what they were supposed to.

If the therapy proves successful, Blumstein said, one effect she'll be watching for is whether it allows people with aphasia to speak more, not just more accurately. That would represent the fullest restoration of expression and language communication.

INFORMATION:

Strengthening speech networks to treat aphasia

2013-02-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

When good habits go bad

2013-02-16

BOSTON, MA -- Learning, memory and habits are encoded in the strength of connections between neurons in the brain, the synapses. These connections aren't meant to be fixed, they're changeable, or plastic.

Duke University neurologist and neuroscientist Nicole Calakos studies what happens when those connections aren't as adaptable as they should be in the basal ganglia, the brain's "command center" for turning information into actions.

"The basal ganglia is the part of the brain that drives the car when you're not thinking too hard about it," Calakos said. It's also ...

Mussels cramped by environmental factors

2013-02-16

The fibrous threads helping mussels stay anchored – in spite of waves that sometimes pound the shore with a force equivalent to a jet liner flying at 600 miles per hour – are more prone to snap when ocean temperatures climb higher than normal.

At the American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in Boston, Emily Carrington, a University of Washington professor of biology, reported that the fibrous threads she calls "nature's bungee cords" become 60 percent weaker in water that was 15 degrees F (7 C) above typical summer temperatures where the mussels were ...

Mussel-inspired 'glue' for surgical repair and cancer drug delivery

2013-02-16

When it comes to sticking power under wet conditions, marine mussels are hard to beat. They can adhere to virtually all inorganic and organic surfaces, sustaining their tenacious bonds in saltwater, including turbulent tidal environments.

Northwestern University's Phillip B. Messersmith will discuss his research in a talk titled "Mussel-Inspired Materials for Surgical Repair and Drug Delivery" at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) annual meeting in Boston. His presentation is part of the symposium "Translation of Mussel Adhesion to Beneficial ...

Using transportation data to predict pandemics

2013-02-16

In a world of increasing global connections, predicting the spread of infectious diseases is more complicated than ever. Pandemics no longer follow the patterns they did centuries ago, when diseases swept through populations town by town; instead, they spread quickly and seemingly at random, spurred by the interactions of 3 billion air travelers per year.

A computational model developed by Northwestern University's Dirk Brockmann could provide better insight into how today's diseases might strike. Brockmann, an associate professor of engineering sciences and applied mathematics ...

Historic legacy of lead pollution persists despite regulatory efforts

2013-02-16

Efforts to reduce lead pollution have paid off in many ways, yet the problem persists and will probably continue to affect the health of people and animals well into the future, according to experts speaking at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in Boston.

"Things have substantially improved with the virtual elimination of leaded gasoline, restrictions on lead paint, and other efforts to limit releases of industrial lead into the environment. But the historic legacy of lead pollution persists, and new inputs of industrial ...

Studying networks to help women succeed in science

2013-02-16

For women in science and research, finding a network of colleagues in their specialized area might be difficult: relevant researchers and activists can be spread across generations, cultures and continents. Finding a mentor within this group proves particularly difficult for young women and minorities.

Northwestern University's Noshir Contractor will discuss his network research in a presentation titled "Understanding and Enabling Networks Among Women's Groups in Sustainable Development" at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) annual meeting ...

Teaching the brain to speak again

2013-02-16

Cynthia Thompson, a world-renowned researcher on stroke and brain damage, will discuss her groundbreaking research on aphasia and the neurolinguistic systems it affects Feb. 16 at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). An estimated one million Americans suffer from aphasia, affecting their ability to understand and/or produce spoken and/or written language.

Thompson, Northwestern's Ralph and Jean Sundin Professor of Communication Sciences, will participate in a 10 a.m. media briefing on "Tools for Regaining Speech" in Room ...

Modern life may cause sun exposure, skin pigmentation mismatch

2013-02-16

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- As people move more often and become more urbanized, skin color -- an adaptation that took hundreds of thousands of years to develop in humans -- may lose some of its evolutionary advantage, according to a Penn State anthropologist.

About 2 million years ago, permanent dark skin color imparted by the pigment -- melanin -- began to evolve in humans to regulate the body's reaction to ultraviolet rays from the sun, said Nina Jablonski, Distinguished Professor of Anthropology.

Melanin helped humans maintain the delicate balance between too much ...

Flow of research on ice sheets helps answer climate questions

2013-02-16

UNIVERSITY PARK, PA. -- Just as ice sheets slide slowly and steadily into the ocean, researchers are returning from each trip to the Arctic and Antarctic with more data about climate change, including information that will help improve current models on how climate change will affect life on the earth, according to a Penn State geologist.

"It is not just correlation, it is causation," said Richard Alley, Evan Pugh Professor of Geosciences. "We know that warming is happening and it's causing the sea levels to rise and if we expect more warming, we can expect the sea levels ...

Academics grapple with balancing their research with the need to communicate it to the public

2013-02-16

BOSTON – Researchers today more than ever focus their work on real-world problems, often times making their research relevant to the public locally, regionally and sometimes nationally. But engaging the public in their research can be a daunting task for researchers both professionally and personally.

Leah Gerber, an Arizona State University associate professor in the School of Life Sciences and a senior sustainability scientist in the School of Sustainability, has identified impediments to productive science communication and she shared her recommendations at the 2013 ...