(Press-News.org) ANN ARBOR, Mich. — An antidepressant drug used since the 1960s may also hold promise for treating sickle cell disease, according to a surprising new finding made in mice and human red blood cells by a team from the University of Michigan Medical School.

The discovery that tranylcypromine, or TCP, can essentially reverse the effects of sickle cell disease was made by U-M scientists who have spent more than three decades studying the basic biology of the condition, with funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Their findings, published in Nature Medicine, pave the way for a clinical trial now being planned for adult patients who have the life-threatening condition. The discovery may also lead to other treatments for the disease, which leads misshapen red blood cells to cause vascular damage and premature death.

But the researchers caution it is too soon for the drug to be used in routine treatment of sickle cell anemia, an inherited genetic disease that affects tens of thousands of Americans and millions of others worldwide.

The climax of a decade of discovery

In the new paper, the researchers describe a painstaking effort to test TCP's effect on the body's production of a particular form of hemoglobin – the key protein that allows red blood cells to carry oxygen.

The drug acts on a molecule inside red blood cells called LSD1, which is involved in blocking the production of the fetal form of hemoglobin. The U-M team zeroed in on the importance of LSD1 as a drug target after many years of research.

Then, they literally did a Google search to find drugs that act on LSD1. That's how they found TCP, which since 1960 has been used to treat severe depression.

In the new paper, they describe how TCP blocked LSD1 and boosted the production of fetal hemoglobin -- offsetting the devastating impact of the abnormal "adult" form of hemoglobin that sickle cell patients make.

"This is the first time that fetal hemoglobin synthesis was re-activated both in human blood cells and in mice to such a high level using a drug, and it demonstrates that once you understand the basic biological mechanism underlying a disease, you can develop drugs to treat it," says Doug Engel, Ph.D., senior author of the study and chair of U-M's Department of Cell & Developmental Biology. "This grew out of an effort to discover the details of how hemoglobin is made during development, not with an immediate focus on curing sickle cell anemia, but just toward understanding it."

Engel credits the dedication and persistence of his team, including a former research assistant professor, Osamu Tanabe, M.D., Ph.D., now at Japan's Tohoku University, U-M postdoctoral fellow, Lihong Shi, Ph.D., first author of the study, and research instructor Shuaiying Cui, Ph.D..

Together, they have identified LSD1's crucial role, and its epigenetic interaction with two nuclear receptors in the nuclei of red blood cell precursors called TR2 and TR4. Working in tandem, they repress the expression of the gene that makes fetal hemoglobin – an effect called gene silencing. So, interfering with this repression allows the fetal hemoglobin subunits to be made.

Treatment with TCP caused fetal hemoglobin to be produced at such high abundance that it made up 30 percent of all hemoglobin in cultured human blood cells – a finding Engel called "startling." TCP is FDA-approved, though patients taking it need to follow strict dietary guidelines to avoid drug interactions with certain naturally occurring chemicals in some foods.

Boosting healthy hemoglobin

Sickle cell disease occurs when a person or animal inherits two defective copies of a gene that governs the production of the "adult" form of hemoglobin. James Neel, the first chair of the U-M Department of Human Genetics, co-discovered the genetic basis for the disease in the late 1940s.

People with just one copy of the mutated gene normally do not get sick, but if they have a child with another person who carries the same trait, there is a one in four chance the child will develop the disease. An estimated 2.5 million Americans – including one in every 12 African Americans and one in every 100 Latinos – carry one copy of the mutated globin gene.

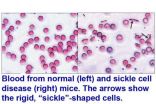

In sickle cell disease, the body makes a form of adult hemoglobin that can aggregate to cause red blood cells to become C-shaped or "sickle" shaped, and stiff and sticky. Those cells clog small blood vessels in the limbs and internal organs, causing organ damage, pain, and raising the risk of infection. Life expectancy in these patients is greatly shortened.

In a very small number of sickle cell patients, the 'fetal' form of hemoglobin – which is usually only made in the womb and the first couple of months of life – keeps being produced throughout life. These patients have symptoms that are either far less severe or nonexistent.

The most common current sickle cell treatment, oral hydroxyurea, aims to boost fetal hemoglobin production. Others, including transfusions and stem cell (bone marrow) transplants from unrelated donors, aim to exchange the source of the overall red blood cell supply.

More study needed

Andrew Campbell, M.D., who directs the Pediatric Comprehensive Sickle Cell program at U-M's C.S. Mott Children's Hospital and has worked with Engel on previous research, finds the new findings are very exciting news for sickle cell patients, since there are not enough treatment options. But, he notes, more clinical research is needed to determine if the findings from mice and cultured human red cell precursors will translate to humans for TCP or even other drugs that inactivate LSD1.

The first such clinical trial is now being planned with the sickle cell team at Wayne State University in Detroit. Further information will be available later this year if it receives approval to go forward. At the same time, U-M is exploring other possible drug candidates targeting the same pathway.

Engel is working with U-M psychiatrist Juan Lopez, M.D., to study the effect of TCP -- and other antidepressants in the class known as monoamine oxidase inhibitors -- on hemoglobin production in adults. The study is still seeking volunteers who are already taking these drugs to treat major depression. To learn more about that study, email gweinber@umich.edu.

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by NIH grants DK086956 and HL24415 and an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship, as well as NCI and Medical School support to the Vector, Flow Cytometry, DNA sequencing and Microarray Cores. U-M has filed for a patent on the discovery.

Reference: Nature Medicine, http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nm.3101

Could an old antidepressant treat sickle cell disease?

Tests in mice & human blood cells look promising

2013-02-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Buying ad time just got easier

2013-02-19

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Today's consumers switch between media forms so often – from TV to laptops to smart phones – that capturing their attention with advertising has gone, as one CEO explained, from shooting fish in a barrel to shooting minnows.

Now, a Michigan State University business scholar and colleagues have developed the most accurate model yet for targeting those fast-moving minnows. The research-based model predicts when during the day people use the varying forms of media and even when they are using two or more at a time, an increasingly common practice known ...

Could a computer on the police beat prevent violence?

2013-02-19

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — As cities across America work to reduce violence in tight budget times, new research shows how they might be able to target their efforts and police attention – with the help of high-powered computers and loads of data.

In a newly published paper, University of Michigan Medical School researchers and their colleagues have used real police data from Boston to demonstrate the promise of computer models in zeroing in on violent areas.

They combined and analyzed information in small geographic units, on police reports, drug offenses, and alcohol availability ...

Russian fireball largest ever detected by CTBTO's infrasound sensors

2013-02-19

Infrasonic waves from the meteor that broke up over Russia's Ural mountains last week were the largest ever recorded by the CTBTO's International Monitoring System. Infrasound is low frequency sound with a range of less than 10 Hz. The blast was detected by 17 infrasound stations in the CTBTO's network, which tracks atomic blasts across the planet. The furthest station to record the sub-audible sound was 15,000km away in Antarctica.

The origin of the low frequency sound waves from the blast was estimated at 03:22 GMT on 15 February 2013. People cannot hear the low frequency ...

Researchers create semiconductor 'nano-shish-kebabs' with potential for 3-D technologies

2013-02-19

Researchers at North Carolina State University have developed a new type of nanoscale structure that resembles a "nano-shish-kebab," consisting of multiple two-dimensional nanosheets that appear to be impaled upon a one-dimensional nanowire. But looks can be deceiving, as the nanowire and nanosheets are actually a single, three-dimensional structure consisting of a single, seamless series of germanium sulfide (GeS) crystals. The structure holds promise for use in the creation of new, three-dimensional (3-D) technologies.

The researchers believe this is the first engineered ...

Theory of crystal formation complete again

2013-02-19

Exactly how a crystal forms from solution is a problem that has occupied scientists for decades. Researchers at Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e), together with researchers from Germany and the USA, are now presenting the missing piece. This classical theory of crystal formation, which occurs widely in nature and in the chemical industry, was under fire for some years, but is saved now. The team made this breakthrough by detailed study of the crystallization of the mineral calcium phosphate –the major component of our bones. The team published their findings yesterday ...

New study shows how seals sleep with only half their brain at a time

2013-02-19

TORONTO, ON – A new study led by an international team of biologists has identified some of the brain chemicals that allow seals to sleep with half of their brain at a time.

The study was published this month in the Journal of Neuroscience and was headed by scientists at UCLA and the University of Toronto. It identified the chemical cues that allow the seal brain to remain half awake and asleep. Findings from this study may explain the biological mechanisms that enable the brain to remain alert during waking hours and go off-line during sleep.

"Seals do something biologically ...

We know when we're being lazy thinkers

2013-02-19

Are we intellectually lazy? Yes we are, but we do know when we take the easy way out, according to a new study by Wim De Neys and colleagues, from the CNRS in France. Contrary to what psychologists believe, we are aware that we occasionally answer easier questions rather than the more complex ones we were asked, and we are also less confident about our answers when we do. The work is published online in Springer's journal Psychonomic Bulletin & Review.

Research to date on human thinking suggests that our judgment is often biased because we are intellectually lazy, or ...

NYU's Shedlin publishes study on the health of Colombian refugees in Ecuador

2013-02-19

New York University College of Nursing's Professor Michele Shedlin, PhD, recently published a paper, "Sending-Country Violence and Receiving-Country Discrimination: Effects on the Health of Colombian Refugees in Ecuador," on-line in the Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, February 2, 2013.

Studies of immigrant health have historically focused on individual-level risk factors more than environmental/structural factors as salient mediating variables. Shedlin's research addresses the need to reach a more complete understanding of the migration process and vulnerabilities ...

Study shows that diet of resistant starch helps the body resist colorectal cancer

2013-02-19

As the name suggests, you can't digest resistant starch so it ends up in the bowel in pretty much the same form it entered your mouth. As unlovely as that seems, once in the bowel this resistant starch does some important things, including decreasing bowel pH and transit time, and increasing the production of short-chain fatty acids. These effects promote the growth of good bugs while keeping bad bugs at bay. A University of Colorado Cancer Center review published in this month's issue of the journal Current Opinion in Gastroenterology shows that resistant starch also helps ...

Annals of Internal Medicine tip sheet for Feb. 19, 2013

2013-02-19

1. Acupuncture May be an Effective Alternative for Treating Seasonal Allergies

Patients receiving acupuncture treatments for seasonal allergic rhinitis reported statistically significant improvements in symptoms and decreased use of medication compared to patients having standard treatment or sham acupuncture, but the clinical significance of the observed improvements is uncertain. Allergic rhinitis (stuffy or runny nose caused by allergies) is an extremely common condition that affects approximately 20 percent of the U.S. population. Despite the availability of effective ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Could an old antidepressant treat sickle cell disease?Tests in mice & human blood cells look promising