(Press-News.org) A new study has examined how bacteria clog medical devices, and the result isn't pretty. The microbes join to create slimy ribbons that tangle and trap other passing bacteria, creating a full blockage in a startlingly short period of time.

The finding could help shape strategies for preventing clogging of devices such as stents — which are implanted in the body to keep open blood vessels and passages — as well as water filters and other items that are susceptible to contamination. The research was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

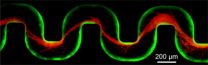

Click on the image to view movie. Over a period of about 40 hours, bacterial cells (green) flowed through a channel, forming a green biofilm on the walls. Over the next ten hours, researchers sent red bacterial cells through the channel. The red cells became stuck in the sticky biofilm and began to form thin red streamers. Once stuck, these streamers in turn trapped additional cells, leading to rapid clogging. (Image source: Knut Drescher)

Using time-lapse imaging, researchers at Princeton University monitored fluid flow in narrow tubes or pores similar to those used in water filters and medical devices. Unlike previous studies, the Princeton experiment more closely mimicked the natural features of the devices, using rough rather than smooth surfaces and pressure-driven fluid instead of non-moving fluid.

VIDEO:

This video shows how, over a period of about 40 hours, bacterial cells (green) flowing through the tube form a green biofilm on the walls. Over the next ten hours,...

Click here for more information.

The team of biologists and engineers introduced a small number of bacteria known to be common contaminants of medical devices. Over a period of about 40 hours, the researchers observed that some of the microbes — dyed green for visibility — attached to the inner wall of the tube and began to multiply, eventually forming a slimy coating called a biofilm. These films consist of thousands of individual cells held together by a sort of biological glue.

Over the next several hours, the researchers sent additional microbes, dyed red, into the tube. These red cells became stuck to the biofilm-coated walls, where the force of the flowing liquid shaped the trapped cells into streamers that rippled in the liquid like flags rippling in a breeze. During this time, the fluid flow slowed only slightly.

At about 55 hours into the experiment, the biofilm streamers tangled with each other, forming a net-like barrier that trapped additional bacterial cells, creating a larger barrier which in turn ensnared more cells. Within an hour, the entire tube became blocked and the fluid flow stopped.

The study was conducted by lead author Knut Drescher with assistance from technician Yi Shen. Drescher is a postdoctoral research associate working with Bonnie Bassler, Princeton's Squibb Professor in Molecular Biology and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, and Howard Stone, Princeton's Donald R. Dixon '69 and Elizabeth W. Dixon Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering.

"For me the surprise was how quickly the biofilm streamers caused complete clogging," said Stone. "There was no warning that something bad was about to happen."

VIDEO:

Biofilm streamers cause rapid and sudden clogging, as shown in this video of fluid flow through a microfluidic channel. Contrary to the current paradigm, the wall-attached biofilm that builds up...

Click here for more information.

By constructing their own controlled environment, the researchers demonstrated that rough surfaces and pressure driven flow are characteristics of nature and need to be taken into account experimentally. The researchers used stents, soil-based filters and water filters to prove that the biofilm streams indeed form in real scenarios and likely explain why devices fail.

The work also allowed the researchers to explore which bacterial genes contribute to biofilm streamer formation. Previous studies, conducted under non-realistic conditions, identified several genes involved in formation of the biofilm streamers. The Princeton researchers found that some of those previously identified genes were not needed for biofilm streamer formation in the more realistic habitat.

INFORMATION:

Read the abstract.

Drescher, Knut, Yi Shen, Bonnie L. Bassler, and Howard A. Stone. 2013. Biofilm streamers cause catastrophic disruption of flow with consequences for environmental and medical systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Published online February 11.

This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical

Institute, National Institutes of Health grant 5R01GM065859, National Science Foundation (NSF) grant MCB-0343821, NSF grant MCB-1119232, and the Human Frontier Science Program.

How do bacteria clog medical devices? Very quickly.

2013-03-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New study could explain why some people get zits and others don't

2013-03-01

The bacteria that cause acne live on everyone's skin, yet one in five people is lucky enough to develop only an occasional pimple over a lifetime.

In a boon for teenagers everywhere, a UCLA study conducted with researchers at Washington University in St. Louis and the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute has discovered that acne bacteria contain "bad" strains associated with pimples and "good" strains that may protect the skin.

The findings, published in the Feb. 28 edition of the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, could lead to a myriad of new therapies to ...

Where the wild things go… when there's nowhere else

2013-03-01

Ecologists have evidence that some endangered primates and large cats faced with relentless human encroachment will seek sanctuary in the sultry thickets of mangrove and peat swamp forests. These harsh coastal biomes are characterized by thick vegetation — particularly clusters of salt-loving mangrove trees — and poor soil in the form of highly acidic peat, which is the waterlogged remains of partially decomposed leaves and wood. As such, swamp forests are among the few areas in many African and Asian countries that humans are relatively less interested in exploiting (though ...

Thyroid hormones reduce damage and improve heart function after myocardial infarction in rats

2013-03-01

Thyroid hormone treatment administered to rats at the time of a heart attack (myocardial infarction) led to significant reduction in the loss of heart muscle cells and improvement in heart function, according to a study published by a team of researchers led by A. Martin Gerdes and Yue-Feng Chen from New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine.

The findings, published in the Journal of Translational Medicine, have bolstered the researchers' contention that thyroid hormones may help reduce heart damage in humans with cardiac diseases.

"I am extremely ...

Groundbreaking UK study shows key enzyme missing from aggressive form of breast cancer

2013-03-01

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Feb. 28, 2013) – A groundbreaking new study led by the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center's Dr. Peter Zhou found that triple-negative breast cancer cells are missing a key enzyme that other cancer cells contain — providing insight into potential therapeutic targets to treat the aggressive cancer. Zhou's study is unique in that his lab is the only one in the country to specifically study the metabolic process of triple-negative breast cancer cells.

Normally, all cells — including cancerous cells — use glucose to initiate the process of making Adenosine-5'-triphosphate ...

Lost in translation: HMO enrollees with poor health have hardest time communicating with doctors

2013-03-01

In the nation's most diverse state, some of the sickest Californians often have the hardest time communicating with their doctors. So say the authors of a new study from the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research that found that residents with limited English skills who reported the poorest health and were enrolled in commercial HMO plans were more likely to have difficulty understanding their doctors, placing this already vulnerable population at even greater risk.

The findings are significant given that, in 2009, nearly one in eight HMO enrollees in California was ...

Study shows need for improved empathic communication between hospice teams and caregivers

2013-03-01

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Feb. 26, 2013) — A new study authored by University of Kentucky researcher Elaine Wittenberg-Lyles shows that more empathic communication is needed between caregivers and hospice team members.

The study, published in Patient Education and Counseling, was done in collaboration with Debra Parker Oliver, professor in the University of Missouri Department of Family and Community Medicine. The team enrolled hospice family caregivers and interdisciplinary team members at two hospice agencies in the Midwestern United States.

Researchers analyzed the bi-weekly ...

New method for researching understudied malaria-spreading mosquitoes

2013-03-01

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute have developed a new method for studying the complex molecular workings of Anopheles albimanus, an important but less studied spreader of human malaria. An. albimanus carries Plasmodium vivax, the primary cause of malaria in humans in South America and regions outside of Africa. Unlike Anopheles gambiae, the genome of the An. albimanus mosquito has not been sequenced and since these two species are evolutionarily divergent, the genome sequence of An. gambiae cannot serve as an appropriate reference. The researcher's ...

Nearly 1 in 4 women newly diagnosed with breast cancer

2013-03-01

A study by researchers at the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center (HICCC) at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, has found that nearly one in four women (23 percent) newly diagnosed with breast cancer reported symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) shortly after diagnosis, with increased risk among black and Asian women. The research has been e-published ahead of print in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

"This study is one of the first to evaluate the course of PTSD after a diagnosis of breast cancer," said ...

British Columbia traffic deaths could be cut in half

2013-03-01

A study by a Simon Fraser University researcher shows British Columbia has much higher traffic death rates than most northern European countries. Comparisons to the safest country, the Netherlands, suggest B.C. could reduce the number of traffic deaths by more than 200 per year.

It also found that fatality and injury risks varied by travel mode.

"Many studies have shown that overall, considering both potential physical activity benefits and injury risks, cycling and walking are on the whole very healthy travel activities," says SFU health sciences assistant professor ...

Mineral diversity clue to early Earth chemistry

2013-03-01

Washington, D.C.— Mineral evolution is a new way to look at our planet's history. It's the study of the increasing diversity and characteristics of Earth's near-surface minerals, from the dozen that arrived on interstellar dust particles when the Solar System was formed to the more than 4,700 types existing today. New research on a mineral called molybdenite by a team led by Robert Hazen at Carnegie's Geophysical Laboratory provides important new insights about the changing chemistry of our planet as a result of geological and biological processes.

The work is published ...