(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A study published in the journal Science reveals a decline in bee species since the late 1800s in West Central Illinois. The study could not have been conducted without the work of a 19th-century naturalist, says a co-author of the new research.

Charles Robertson, a self-taught entomologist who studied zoology and botany at Harvard University and the University of Illinois, was one of the first scientists to make detailed records of the interactions of wild bees and the plants they pollinate, says John Marlin, a co-author of the new analysis in Science. In the 1970s, Marlin, a research affiliate with the Illinois Sustainable Technology Center and Illinois Natural History Survey at the U. of I., used Robertson's records as a basis for his own research on the wild bees around Carlinville, Ill., an area rich in woodlands and native prairie.

Marlin's research was documented in a 2001 Ecology and Society article ("The Native Bee Fauna of Carlinville, Illinois, Revisited After 75 Years: a Case for Persistence"). That study focused on the 24 plant species that Robertson had found harbored the most bee species. Seventy-five years after Robertson's research, Marlin found 82 percent of the species Robertson had collected in the original study.

The new article in Science, by Laura Burkle, of Montana State University, Marlin and Tiffany Knight, of Washington University, shows a considerable decline in the number of bee species in the Carlinville area since both the Robertson and Marlin studies. On spring woodland wildflowers they found only half of the bee species that Robertson originally documented.

"This is an indication that something dramatic has happened to the landscape," Marlin said.

"Carlinville is one of the most referenced communities in the world in the bee literature," Marlin said. "It is clear that Charles Robertson's foundation provides an invaluable resource for modern comparative studies on bee species and their interactions with the environment."

The center and survey are part of the Prairie Research Institute at Illinois.

INFORMATION:

Editor's notes: To reach John Marlin, call 217-649-4591 ; email marlin@illinois.edu.

The paper, "Plant-pollinator interactions over 120 years: loss of species,

co-occurrence and function," is available online at http://www.sciencemag.org/content/early/2013/02/27/science.1232728.full.pdf or from the U. of I. News Bureau. Written by Chelsey B. Coombs, News Bureau intern.

Illinois town provides a historical foundation for today's bee research

2013-03-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New chemical probe provides tool to investigate role of malignant brain tumor domains

2013-03-01

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – In an article published as the cover story of the March 2013 issue of Nature Chemical Biology, Lindsey James, PhD, research assistant professor in the lab of Stephen Frye, Fred Eshelman Distinguished Professor in the UNC School of Pharmacy and member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, announced the discovery of a chemical probe that can be used to investigate the L3MBTL3 methyl-lysine reader domain. The probe, named UNC1215, will provide researchers with a powerful tool to investigate the function of malignant brain tumor (MBT) domain ...

Study confirms safety of colonoscopy

2013-03-01

Colon cancer develops slowly. Precancerous lesions usually need many years to turn into a dangerous carcinoma. They are well detectable in an endoscopic examination of the colon called colonoscopy and can be removed during the same examination. Therefore, regular screening can prevent colon cancer much better than other types of cancer. Since 2002, colonoscopy is part of the national statutory cancer screening program in Germany for all insured persons aged 55 or older.

However, only one fifth of those eligible actually make use of the screening program. The reasons ...

Towards more sustainable construction

2013-03-01

This press release is available in French.

Montreal, March 1, 2013 – Construction in Montreal is under a microscope. Now more than ever, municipal builders need to comply with long-term urban planning goals. The difficulties surrounding massive projects like the Turcot interchange lead Montrealers to wonder if construction in this city is headed in the right direction. New research from Concordia University gives us hope that this could soon be the case if sufficient effort is made.

A team of graduate students from Concordia's Department of Geography, Planning and Environment ...

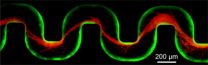

How do bacteria clog medical devices? Very quickly.

2013-03-01

A new study has examined how bacteria clog medical devices, and the result isn't pretty. The microbes join to create slimy ribbons that tangle and trap other passing bacteria, creating a full blockage in a startlingly short period of time.

The finding could help shape strategies for preventing clogging of devices such as stents — which are implanted in the body to keep open blood vessels and passages — as well as water filters and other items that are susceptible to contamination. The research was published in Proceedings of the National ...

New study could explain why some people get zits and others don't

2013-03-01

The bacteria that cause acne live on everyone's skin, yet one in five people is lucky enough to develop only an occasional pimple over a lifetime.

In a boon for teenagers everywhere, a UCLA study conducted with researchers at Washington University in St. Louis and the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute has discovered that acne bacteria contain "bad" strains associated with pimples and "good" strains that may protect the skin.

The findings, published in the Feb. 28 edition of the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, could lead to a myriad of new therapies to ...

Where the wild things go… when there's nowhere else

2013-03-01

Ecologists have evidence that some endangered primates and large cats faced with relentless human encroachment will seek sanctuary in the sultry thickets of mangrove and peat swamp forests. These harsh coastal biomes are characterized by thick vegetation — particularly clusters of salt-loving mangrove trees — and poor soil in the form of highly acidic peat, which is the waterlogged remains of partially decomposed leaves and wood. As such, swamp forests are among the few areas in many African and Asian countries that humans are relatively less interested in exploiting (though ...

Thyroid hormones reduce damage and improve heart function after myocardial infarction in rats

2013-03-01

Thyroid hormone treatment administered to rats at the time of a heart attack (myocardial infarction) led to significant reduction in the loss of heart muscle cells and improvement in heart function, according to a study published by a team of researchers led by A. Martin Gerdes and Yue-Feng Chen from New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine.

The findings, published in the Journal of Translational Medicine, have bolstered the researchers' contention that thyroid hormones may help reduce heart damage in humans with cardiac diseases.

"I am extremely ...

Groundbreaking UK study shows key enzyme missing from aggressive form of breast cancer

2013-03-01

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Feb. 28, 2013) – A groundbreaking new study led by the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center's Dr. Peter Zhou found that triple-negative breast cancer cells are missing a key enzyme that other cancer cells contain — providing insight into potential therapeutic targets to treat the aggressive cancer. Zhou's study is unique in that his lab is the only one in the country to specifically study the metabolic process of triple-negative breast cancer cells.

Normally, all cells — including cancerous cells — use glucose to initiate the process of making Adenosine-5'-triphosphate ...

Lost in translation: HMO enrollees with poor health have hardest time communicating with doctors

2013-03-01

In the nation's most diverse state, some of the sickest Californians often have the hardest time communicating with their doctors. So say the authors of a new study from the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research that found that residents with limited English skills who reported the poorest health and were enrolled in commercial HMO plans were more likely to have difficulty understanding their doctors, placing this already vulnerable population at even greater risk.

The findings are significant given that, in 2009, nearly one in eight HMO enrollees in California was ...

Study shows need for improved empathic communication between hospice teams and caregivers

2013-03-01

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Feb. 26, 2013) — A new study authored by University of Kentucky researcher Elaine Wittenberg-Lyles shows that more empathic communication is needed between caregivers and hospice team members.

The study, published in Patient Education and Counseling, was done in collaboration with Debra Parker Oliver, professor in the University of Missouri Department of Family and Community Medicine. The team enrolled hospice family caregivers and interdisciplinary team members at two hospice agencies in the Midwestern United States.

Researchers analyzed the bi-weekly ...