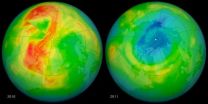

(Press-News.org) A combination of extreme cold temperatures, man-made chemicals and a stagnant atmosphere were behind what became known as the Arctic ozone hole of 2011, a new NASA study finds.

Even when both poles of the planet undergo ozone losses during the winter, the Arctic's ozone depletion tends to be milder and shorter-lived than the Antarctic's. This is because the three key ingredients needed for ozone-destroying chemical reactions —chlorine from man-made chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), frigid temperatures and sunlight— are not usually present in the Arctic at the same time: the northernmost latitudes are generally not cold enough when the sun reappears in the sky in early spring. Still, in 2011, ozone concentrations in the Arctic atmosphere were about 20 percent lower than its late winter average.

The new study shows that, while chlorine in the Arctic stratosphere was the ultimate culprit of the severe ozone loss of winter of 2011, unusually cold and persistent temperatures also spurred ozone destruction. Furthermore, uncommon atmospheric conditions blocked wind-driven transport of ozone from the tropics, halting the seasonal ozone resupply until April.

"You can safely say that 2011 was very atypical: In over 30 years of satellite records, we hadn't seen any time where it was this cold for this long," said Susan E. Strahan, an atmospheric scientist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., and main author of the new paper, which was recently published in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres.

"Arctic ozone levels were possibly the lowest ever recorded, but they were still significantly higher than the Antarctic's," Strahan said. " There was about half as much ozone loss as in the Antarctic and the ozone levels remained well above 220 Dobson units, which is the threshold for calling the ozone loss a 'hole' in the Antarctic – so the Arctic ozone loss of 2011 didn't constitute an ozone hole."

The majority of ozone depletion in the Arctic happens inside the so-called polar vortex: a region of fast-blowing circular winds that intensify in the fall and isolate the air mass within the vortex, keeping it very cold.

VIDEO:

This animation shows the dynamics of the ozone layer from January 1 to March 23, in both 2010 and 2011. Recent observations from satellites and ground stations suggest that atmospheric...

Click here for more information.

Most years, atmospheric waves knock the vortex to lower latitudes in later winter, where it breaks up. In comparison, the Antarctic vortex is very stable and lasts until the middle of spring. But in 2011, an unusually quiescent atmosphere allowed the Arctic vortex to remain strong for four months, maintaining frigid temperatures even after the sun reappeared in March and promoting the chemical processes that deplete ozone.

The vortex also played another role in the record ozone low.

"Most ozone found in the Arctic is produced in the tropics and is transported to the Arctic," Strahan said. "But if you have a strong vortex, it's like locking the door -- the ozone can't get in."

To determine whether the mix of man-made chemicals and extreme cold or the unusually stagnant atmospheric conditions was primarily responsible for the low ozone levels observed, Strahan and her collaborators used an atmospheric chemistry and transport model (CTM) called the Global Modeling Initiative (GMI) CTM. The team ran two simulations: one that included the chemical reactions that occur on polar stratospheric clouds, the tiny ice particles that only form inside the vortex when it's very cold, and one without. They then compared their results to real ozone observations from NASA's Aura satellite.

The results from the first simulation reproduced the real ozone levels very closely, but the second simulation showed that, even if chlorine pollution hadn't been present, ozone levels would still have been low due to lack of transport from the tropics. Strahan's team calculated that the combination of chlorine pollution and extreme cold temperatures were responsible for two thirds of the ozone loss, while the remaining third was due to the atypical atmospheric conditions that blocked ozone resupply.

Once the vortex broke down and transport from the tropics resumed, the ozone concentrations rose quickly and reached normal levels in April 2011.

Strahan, who now wants to use the GMI model to study the behavior of the ozone layer at both poles during the past three decades, doesn't think it's likely there will be frequent large ozone losses in the Arctic in the future.

"It was meteorologically a very unusual year, and similar conditions might not happen again for 30 years," Strahan said. "Also, chlorine levels are going down in the atmosphere because we've stopped producing a lot of CFCs as a result of the Montreal Protocol. If 30 years from now we had the same meteorological conditions again, there would actually be less chlorine in the atmosphere, so the ozone depletion probably wouldn't be as severe."

INFORMATION:

NASA pinpoints causes of 2011 Arctic ozone hole

2013-03-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NASA's SDO observes Earth, lunar transits in same day

2013-03-12

On March 2, 2013, NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) entered its semiannual eclipse season, a period of three weeks when Earth blocks its view of the sun for a period of time each day. On March 11, however, SDO was treated to two transits. Earth blocked SDO's view of the sun from about 2:15 to 3:45 a.m. EDT. Later in the same day, from around 7:30 to 8:45 a.m. EDT, the moon moved in front of the sun for a partial eclipse.

When Earth blocks the sun, the boundaries of Earth's shadow appear fuzzy, since SDO can see some light from the sun coming through Earth's atmosphere. ...

Angioplasty at hospitals without on-site cardiac surgery safe, effective

2013-03-12

SAN FRANCISCO (March 11, 2013) — Non-emergency angioplasty performed at hospitals without on-site cardiac surgery capability is no less safe and effective than angioplasty performed at hospitals with cardiac surgery services, according to research presented today at the American College of Cardiology's 62nd Annual Scientific Session.

Emergency surgery has become an increasingly rare event following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or angioplasty—a non-surgical procedure used to open narrow or blocked coronary arteries and restore blood flow to the heart. This ...

Single concussion may cause lasting brain damage

2013-03-12

OAK BROOK, Ill. – A single concussion may cause lasting structural damage to the brain, according to a new study published online in the journal Radiology.

"This is the first study that shows brain areas undergo measureable volume loss after concussion," said Yvonne W. Lui, M.D., Neuroradiology section chief and assistant professor of radiology at NYU Langone School of Medicine. "In some patients, there are structural changes to the brain after a single concussive episode."

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, each year in the U.S., 1.7 million ...

Biological wires carry electricity thanks to special amino acids

2013-03-12

Slender bacterial nanowires require certain key amino acids in order to conduct electricity, according to a study to be published in mBio®, the online open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology, on Tuesday, March 12.

In nature, the bacterium Geobacter sulfurreducens uses these nanowires, called pili, to transport electrons to remote iron particles or other microbes, but the benefits of these wires can also be harnessed by humans for use in fuel cells or bioelectronics. The study in mBio® reveals that a core of aromatic amino acids are required to turn ...

Kid's consumption of sugared beverages linked to higher caloric intake of food

2013-03-12

San Diego, CA, March 12, 2013 – A new study from the Department of Nutrition, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill reports that sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are primarily responsible for higher caloric intakes of children that consume SSBs as compared to children that do not (on a given day). In addition, SSB consumption is also associated with higher intake of unhealthy foods. The results are published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

Over the past 20 years, consumption of SSBs — sweetened sodas, fruit drinks, sports drinks, and energy drinks ...

Prenatal exposure to pesticide DDT linked to adult high blood pressure

2013-03-12

Infant girls exposed to high levels of the pesticide DDT while still

inside the womb are three times more likely to develop hypertension

when they become adults, according to a new study led by the

University of California, Davis.

Previous studies have shown that adults exposed to DDT

(dichlorodiplhenyltrichloroethane) are at an increased risk of high

blood pressure. But this study, published online March 12 in

Environmental Health Perspectives, is the first to link prenatal DDT

exposure to hypertension in adults.

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a ...

New survey reports low rate of patient awareness during anesthesia

2013-03-12

The Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCoA) and the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) today publish initial findings from a major study which looked at how many patients experienced accidental awareness during general anaesthesia.

The survey asked all senior anaesthetists in NHS hospitals in the UK (more than 80% of whom replied) to report how many cases of accidental awareness during general anaesthesia they encountered in 2011. There are three million general anaesthetics administered each year. Study findings are published in Anaesthesia, ...

Breaking the final barrier: Room-temperature electrically powered nanolasers

2013-03-12

TEMPE, Ariz. -- A breakthrough in nanolaser technology has been made by Arizona State University researchers.

Electrically powered nano-scale lasers have been able to operate effectively only in cold temperatures. Researchers in the field have been striving to enable them to perform reliably at room temperature, a step that would pave the way for their use in a variety of practical applications.

Details of how ASU researchers made that leap are published in a recent issue of the research journal Optics Express (Vol. 21, No. 4, 4728 2013). Read the full article at http://www.opticsinfobase.org/oe/abstract.cfm?URI=oe-21-4-4728 ...

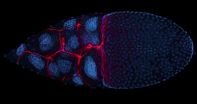

Asterix's Roman foes -- Researchers have a better idea of how cancer cells move and grow

2013-03-12

This press release is available in French.

Researchers at the University of Montreal's Institute for Research in Immunology and Cancer (IRIC) have discovered a new mechanism that allows some cells in our body to move together, in some ways like the tortoise formation used by Roman soldiers depicted in the Asterix series. Collective cell migration is an essential part of our body's growth and defense system, but it is also used by cancerous cells to disseminate efficiently in the body. "We have found a key mechanism that allows cells to coordinate their movement as a ...

Hearts Pest Management, Inc. Lends Their Expertise To The Victims of Pest Invasion

2013-03-12

Hearts Pest Management President, Gerry Weitz, provides his expertise in Ellen Byron's Wall Street Journal article Critter Counteroffiensive from the Personal Journal section published on February 27, 2013.

Critter Counteroffensive focuses on "The tactics to take back the great room from stubborn, furry visitors.'" Gerry Weitz of Hearts Pest Management was one of six nationally recognized pest control companies and their owners to contribute to the article. The article addressed that rats, mice and larger wildlife are among the "furry visitors" that ...