(Press-News.org) Research from the University of Maryland School of Medicine has revealed key features in proteins needed for life to function on Mars and other extreme environments. The researchers, funded by NASA, studied organisms that survive in the extreme environment of Antarctica. They found subtle but significant differences between the core proteins in ordinary organisms and Haloarchaea, organisms that can tolerate severe conditions such as high salinity, desiccation, and extreme temperatures. The research gives scientists a window into how life could possibly adapt to exist on Mars.

The study, published online in the journal PLoS One on March 11, was led by Shiladitya DasSarma, Ph.D., Professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and a research scientist at the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology.

Researchers found that Haloarchaeal microbes contain proteins that are acidic, with their surface covered with negatively charged residues. Most ordinary organisms contain proteins that are neutral on average. The negative charges found in the unusual organisms keep proteins in solution and help to hold on tightly to water, reversing the effects of high salinity and desiccation.

In the current study, the scientists identified additional subtle changes in the proteins of one Haloarchaeal species named Halorubrum lacusprofundi. These microbes were isolated from Deep Lake, a very salty lake in Antarctica. The changes found in proteins from these organisms allow them to work in both cold and salty conditions, when temperatures may be well below the freezing point of pure water. Water stays in the liquid state under these conditions much like snow and ice melt on roads that have been salted in winter.

"In such cold temperatures, the packing of atoms in proteins must be loosened slightly, allowing them to be more flexible and functional when ordinary proteins would be locked into inactive conformations" says Dr. DasSarma. "The surface of these proteins also have modifications that loosen the binding of the surrounding water molecules."

"These kinds of adaptations are likely to allow microorganisms like Halorubrum lacusprofundi to survive not only in Antarctica, but elsewhere in the universe," says Dr. DasSarma. "For example, there have been recent reports of seasonal flows down the steep sides of craters on Mars suggesting the presence of underground brine pools. Whether microorganisms actually exist in such environments is not yet known, but expeditions like NASA's Curiosity rover are currently looking for signs of life on Mars."

"Dr. DasSarma and his colleagues are unraveling the basic building blocks of life," says E. Albert Reece, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A., Vice President for Medical Affairs at the University of Maryland and John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and Dean of the University of Maryland School of Medicine. "Their research into the fundamentals of microbiology are enhancing our understanding of life throughout the universe, and I look forward to seeing further groundbreaking discoveries from their laboratory."

###

Dr. DasSarma and his colleagues are conducting further studies of individual proteins from Halorubrum lacusprofundi, funded by NASA. The adaptations of these proteins could be used to engineer and develop novel enzymes and catalysts. For example, the researchers are examining one model protein, β-galactosidase, that can break down polymerized substances, such as milk sugars, and with the help of other enzymes, even larger polymers. This work may have practical uses such as improving methods for breaking down biological polymers and producing useful materials (see Karan et al. BMC Biotechnology 2013 13:3 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6750/13/3).

University of Maryland School of Medicine discovers adaptations to explain strategies for survival on Mars

Scientists found differences in core proteins from a microorganism that lives in a salty lake in Antarctica

2013-03-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Similar outcomes in older patients with on- or off-pump bypass

2013-03-12

SAN FRANCISCO (March 11, 2013) — Older patients did as well after undergoing coronary bypass surgery off-pump as they did with the more costly "on-pump" procedure using a heart-lung machine to circulate blood and oxygen through the body during surgery, according to research presented today at the American College of Cardiology's 62nd Annual Scientific Session.

This large, multicenter trial—the German Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting in Elderly Patients, called GOPCABE—was the first to evaluate on-pump versus off-pump bypass surgery among patients aged 75 or older. ...

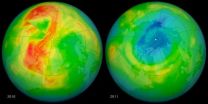

NASA pinpoints causes of 2011 Arctic ozone hole

2013-03-12

A combination of extreme cold temperatures, man-made chemicals and a stagnant atmosphere were behind what became known as the Arctic ozone hole of 2011, a new NASA study finds.

Even when both poles of the planet undergo ozone losses during the winter, the Arctic's ozone depletion tends to be milder and shorter-lived than the Antarctic's. This is because the three key ingredients needed for ozone-destroying chemical reactions —chlorine from man-made chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), frigid temperatures and sunlight— are not usually present in the Arctic at the same time: the ...

NASA's SDO observes Earth, lunar transits in same day

2013-03-12

On March 2, 2013, NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) entered its semiannual eclipse season, a period of three weeks when Earth blocks its view of the sun for a period of time each day. On March 11, however, SDO was treated to two transits. Earth blocked SDO's view of the sun from about 2:15 to 3:45 a.m. EDT. Later in the same day, from around 7:30 to 8:45 a.m. EDT, the moon moved in front of the sun for a partial eclipse.

When Earth blocks the sun, the boundaries of Earth's shadow appear fuzzy, since SDO can see some light from the sun coming through Earth's atmosphere. ...

Angioplasty at hospitals without on-site cardiac surgery safe, effective

2013-03-12

SAN FRANCISCO (March 11, 2013) — Non-emergency angioplasty performed at hospitals without on-site cardiac surgery capability is no less safe and effective than angioplasty performed at hospitals with cardiac surgery services, according to research presented today at the American College of Cardiology's 62nd Annual Scientific Session.

Emergency surgery has become an increasingly rare event following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or angioplasty—a non-surgical procedure used to open narrow or blocked coronary arteries and restore blood flow to the heart. This ...

Single concussion may cause lasting brain damage

2013-03-12

OAK BROOK, Ill. – A single concussion may cause lasting structural damage to the brain, according to a new study published online in the journal Radiology.

"This is the first study that shows brain areas undergo measureable volume loss after concussion," said Yvonne W. Lui, M.D., Neuroradiology section chief and assistant professor of radiology at NYU Langone School of Medicine. "In some patients, there are structural changes to the brain after a single concussive episode."

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, each year in the U.S., 1.7 million ...

Biological wires carry electricity thanks to special amino acids

2013-03-12

Slender bacterial nanowires require certain key amino acids in order to conduct electricity, according to a study to be published in mBio®, the online open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology, on Tuesday, March 12.

In nature, the bacterium Geobacter sulfurreducens uses these nanowires, called pili, to transport electrons to remote iron particles or other microbes, but the benefits of these wires can also be harnessed by humans for use in fuel cells or bioelectronics. The study in mBio® reveals that a core of aromatic amino acids are required to turn ...

Kid's consumption of sugared beverages linked to higher caloric intake of food

2013-03-12

San Diego, CA, March 12, 2013 – A new study from the Department of Nutrition, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill reports that sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are primarily responsible for higher caloric intakes of children that consume SSBs as compared to children that do not (on a given day). In addition, SSB consumption is also associated with higher intake of unhealthy foods. The results are published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

Over the past 20 years, consumption of SSBs — sweetened sodas, fruit drinks, sports drinks, and energy drinks ...

Prenatal exposure to pesticide DDT linked to adult high blood pressure

2013-03-12

Infant girls exposed to high levels of the pesticide DDT while still

inside the womb are three times more likely to develop hypertension

when they become adults, according to a new study led by the

University of California, Davis.

Previous studies have shown that adults exposed to DDT

(dichlorodiplhenyltrichloroethane) are at an increased risk of high

blood pressure. But this study, published online March 12 in

Environmental Health Perspectives, is the first to link prenatal DDT

exposure to hypertension in adults.

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a ...

New survey reports low rate of patient awareness during anesthesia

2013-03-12

The Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCoA) and the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) today publish initial findings from a major study which looked at how many patients experienced accidental awareness during general anaesthesia.

The survey asked all senior anaesthetists in NHS hospitals in the UK (more than 80% of whom replied) to report how many cases of accidental awareness during general anaesthesia they encountered in 2011. There are three million general anaesthetics administered each year. Study findings are published in Anaesthesia, ...

Breaking the final barrier: Room-temperature electrically powered nanolasers

2013-03-12

TEMPE, Ariz. -- A breakthrough in nanolaser technology has been made by Arizona State University researchers.

Electrically powered nano-scale lasers have been able to operate effectively only in cold temperatures. Researchers in the field have been striving to enable them to perform reliably at room temperature, a step that would pave the way for their use in a variety of practical applications.

Details of how ASU researchers made that leap are published in a recent issue of the research journal Optics Express (Vol. 21, No. 4, 4728 2013). Read the full article at http://www.opticsinfobase.org/oe/abstract.cfm?URI=oe-21-4-4728 ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Increased risk of bullying in open-plan offices

Frequent scrolling affects perceptions of the work environment

Brain activity reveals how well we mentally size up others

Taiwanese and UK scientists identify FOXJ3 gene linked to drug-resistant focal epilepsy

Pregnancy complications impact women’s stress levels and cardiovascular risk long after delivery

Spring fatigue cannot be empirically proven

Do prostate cancer drugs interact with certain anticoagulants to increase bleeding and clotting risks?

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

Increased connectivity in early Alzheimer’s is lowered by cancer drug in the lab

Study highlights stroke risk linked to recreational drugs, including among young users

Modeling brain aging and resilience over the lifespan reveals new individual factors

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

[Press-News.org] University of Maryland School of Medicine discovers adaptations to explain strategies for survival on MarsScientists found differences in core proteins from a microorganism that lives in a salty lake in Antarctica