(Press-News.org) AMHERST, Mass. – When researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst led by microbiologist Derek Lovley discovered that the bacterium Geobacter sulfurreducens conducts electricity very effectively along metallic-like "microbial nanowires," they found physicists quite comfortable with the idea of such a novel biological electron transfer mechanism, but not biologists.

"For biologists, Geobacter's behavior represents a paradigm shift. It goes against all that we are taught about biological electron transfer, which usually involves electrons hopping from one molecule to another," Lovley says. "So it wasn't enough for us to demonstrate that the microbial nanowires are conductive and to show with physics the conduction mechanism, we had to determine the impact of this conductivity on the biology."

"We have now identified key components that make these hair-like pili we call nanowires conductive and have demonstrated their importance in the biological electron transport. This time we relied more on genetics. I think most biologists are more comfortable with genetics rather than physics," Lovley adds.

"From my perspective, this is huge. It really clinches a big question. We overturned the major objection the biologists were making and confirmed the assumption in our earlier work, that real metallic-like conductivity is taking place."

Findings are described in an early online issue of mBio, the open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology. In addition to Lovley, the UMass Amherst team includes first author Madeline Vargas, with Nikhil Malvankar, Pier-Luc Tremblay, Ching Leang, Jessica Smith, Pranav Patel, Oona Snoeyenbos-West and Kelly Nevin.

In 2011, Lovely's group discovered a fundamental, previously unknown property of pili in Geobacter. They found that electrons are transported along the pili via the same metallic-like conductivity found in synthetic organic materials used in electronics. Electrons are conducted over remarkable distances, thousands of times the cell's length. But exactly how the pili accomplished this wasn't clear.

They knew that the conductivity of synthetic conducting organic materials can be attributed to aromatic ringed structures which share electrons, suspended in a kind of a cloud that allows the overlapping electrons to easily flow. It seemed possible that amino acids, which have similar aromatic rings, might serve the same function in biological protein structures like pili. Lovley's team looked for likely aromatic amino acid targets and then substituted non-aromatic amino acids for the aromatic ones to see if this reduced the conductivity of the pili.

It worked. The re-engineered pili with non-aromatic compounds substituted for aromatic ones looked perfect and unchanged under a microscope, but now they no longer functioned as wires. "This new strain is really bad at what Geobacter does best," Lovley says. "Geobacter is known for its ability to grow on iron minerals and for generating electric current in microbial fuel cells, but without conductive pili those capabilities are greatly diminished."

"What we did is equivalent to pulling the copper out of an extension cord," he adds. "The cord looks the same, but it can't conduct electricity anymore."

The ability of protein filaments to conduct electrons in this way not only has ramifications for scientists' basic understanding of natural microbial processes but practical implications for environmental cleanup and the development of renewable energy sources as well, he adds. Lovley's UMass Amherst lab has already been working with federal agencies and industry to use Geobacter to clean up groundwater contaminated with radioactive metals or petroleum and to power electronic monitoring devices with current generated by Geobacter.

His group has also recently shown that Geobacter uses its nanowires to feed electrons to other microorganisms that can produce methane gas. This is an important step in the conversion of organic wastes to methane, which can then be burned to produce electricity.

As more states, including national leader Massachusetts, pass laws to prevent hospitals, universities, hotels and large restaurants from disposing of food waste in landfills, Geobacter's role in producing methane could be part of the solution for how to deal with this waste. The Massachusetts law goes into effect in 2014. "Waste to methane is a well developed green energy strategy in Europe and is almost certain to become more important here in Massachusetts in the near future," Lovley notes.

INFORMATION:

Funding for this work was from the U.S. Office of Naval Research and the Department of Energy.

UMass Amherst researchers reveal mechanism of novel biological electron transfer

Researchers at UMass Amherst led by microbiologist Derek Lovley have identified key components that make hair-like pili called nanowires in certain bacteria able to conduct electricity and show their importance in biological electron transport

2013-03-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Sex between monogamous heterosexuals rarely source of hepatitis C infection

2013-03-19

Individuals infected by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) have nothing to fear from sex in a monogamous, heterosexual relationship. Transmission of HCV from an infected partner during sex is rare according to new research published in the March issue of Hepatology, a journal published by Wiley on behalf of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Experts estimate that HCV affects up to 4 million Americans, most of whom are sexually active. Medical evidence shows HCV is primarily transmitted by exposure to infectious blood, typically through intravenous ...

Greenhouse gas policies ignoring gap in household incomes: University of Alberta study

2013-03-19

Government policies aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions from consumers need to be fairer for household income levels, says a University of Alberta researcher.

A U of A study published recently online in the journal Environment and Behaviour looks at the different sources of greenhouse gas emissions from consumers, based on their income levels. The wealthiest households in Alberta emit the most greenhouse gases, but too often, income disparity hasn't been factored in to current polices—such as the carbon flat tax that is levied to British Columbia residents.

Such ...

Kill Bill character inspires the name of a new parasitoid wasp species

2013-03-19

Parasitoid wasps of the family Braconidae are known for their deadly reproductive habits. Most of the representatives of this group have their eggs developing in other insects and their larvae, eventually killing the respective host, or in some cases immobilizing it or causing its sterility. Three new species of the parasitoid wasp genus Cystomastacoides, recently described in the Journal of Hymenoptera Research, reflect this fatal behavior.

Two of the new species were discovered in Papua New Guinea, while the third one comes from Thailand. The Thai species, Cystomastacoides ...

Newly incarcerated have 1 percent acute hepatitis C prevalence

2013-03-19

A study published in the March issue of Hepatology, a journal of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, estimates that the prevalence of acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is nearly one percent among newly incarcerated inmates with a history of recent drug use. Findings suggest that systematic screening of intravenous (IV) drug users who are new to the prison system could identify more than 7,000 cases of HCV across the U.S. annually—even among asymptomatic inmates.

According to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Health—the ...

Pre-college talk between parents and teens likely to lessen college drinking

2013-03-19

Teen-age college students are significantly more likely to abstain from drinking or to drink only minimally when their parents talk to them before they start college, using suggestions in a parent handbook developed by Robert Turrisi, professor of biobehavioral health, Penn State.

"Over 90 percent of teens try alcohol outside the home before they graduate from high school," said Turrisi. "It is well known that fewer problems develop for every year that heavy drinking is delayed. Our research over the past decade shows that parents can play a powerful role in minimizing ...

Brain-mapping increases understanding of alcohol's effects on first-year college students

2013-03-19

A research team that includes several Penn State scientists has completed a first-of-its-kind longitudinal pilot study aimed at better understanding how the neural processes that underlie responses to alcohol-related cues change during students' first year of college.

Anecdotal evidence abounds attesting to the many negative social and physical effects of the dramatic increase in alcohol use that often comes with many students' first year of college. The behavioral changes that accompany those effects indicate underlying changes in the brain. Yet in contrast to alcohol's ...

Conscientious people are more likely to have higher GPAs

2013-03-19

Conscientious people are more likely to have higher grade point averages, according to new research from psychologists at Rice University.

The paper examines previous studies that research the link between the "Big Five" personality traits –agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism and openness to experience – and college grade point average. It finds that across studies, higher levels of conscientiousness lead to higher college grade point averages. It also shows that five common personality tests are consistent in their evaluation of the "Big Five" ...

UCLA researchers create tomatoes that mimic actions of good cholesterol

2013-03-19

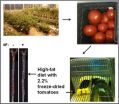

UCLA researchers have genetically engineered tomatoes to produce a peptide that mimics the actions of good cholesterol when consumed.

Published in the April issue of the Journal of Lipid Research and featured on the cover, their early study found that mice that were fed these tomatoes in freeze-dried, ground form had less inflammation and plaque build-up in their arteries.

"This is one of the first examples of a peptide that acts like the main protein in good cholesterol and can be delivered by simply eating the plant," said senior author Dr. Alan M. Fogelman, executive ...

High-carb intake in infancy has lifelong effects, UB study finds

2013-03-19

BUFFALO, N.Y. – Consumption of foods high in carbohydrates immediately after birth programs individuals for lifelong increased weight gain and obesity, a University at Buffalo animal study has found, even if caloric intake is restricted in adulthood for a period of time.

The research on laboratory animals was published this month in the American Journal of Physiology: Endocrinology and Metabolism; it was published online in December.

"This is the first time that we have shown in our rat model of obesity that there is a resistance to the reversal of this programming ...

Dartmouth researchers invent real time secondhand smoke sensor

2013-03-19

Making headway against a major public health threat, Dartmouth College researchers have invented the first ever secondhand tobacco smoke sensor that records data in real time, a new study in the journal Nicotine and Tobacco Research shows.

The researchers expect to soon convert the prototype, which is smaller and lighter than a cellphone, into a wearable, affordable and reusable device that helps to enforce no smoking regulations and sheds light on the pervasiveness of secondhand smoke. The sensor can also detect thirdhand smoke, or nicotine off-gassing from clothing, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Genomics offers a faster path to restoring the American chestnut

Caught in the act: Astronomers watch a vanishing star turn into a black hole

Why elephant trunk whiskers are so good at sensing touch

A disappearing star quietly formed a black hole in the Andromeda Galaxy

Yangtze River fishing ban halts 70 years of freshwater biodiversity decline

Genomic-informed breeding approaches could accelerate American chestnut restoration

How plants control fleshy and woody tissue growth

Scientists capture the clearest view yet of a star collapsing into a black hole

New insights into a hidden process that protects cells from harmful mutations

Yangtze River fishing ban halts seven decades of biodiversity decline

Researchers visualize the dynamics of myelin swellings

Cheops discovers late bloomer from another era

Climate policy support is linked to emotions - study

New method could reveal hidden supermassive black hole binaries

Novel AI model accurately detects placenta accreta in pregnancy before delivery, new research shows

Global Physics Photowalk winners announced

Exercise trains a mouse's brain to build endurance

New-onset nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and initiators of semaglutide in US veterans with type 2 diabetes

Availability of higher-level neonatal care in rural and urban US hospitals

Researchers identify brain circuit and cells that link prior experiences to appetite

Frog love songs and the sounds of climate change

Hunter-gatherers northwestern Europe adopted farming from migrant women, study reveals

Light-based sensor detects early molecular signs of cancer in the blood

3D MIR technique guides precision treatment of kids’ heart conditions

Which childhood abuse survivors are at elevated risk of depression? New study provides important clues

Plants retain a ‘genetic memory’ of past population crashes, study shows

CPR skills prepare communities to save lives when seconds matter

FAU study finds teen ‘sexting’ surge, warns of sextortion and privacy risks

Chinese Guidelines for Clinical Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Cirrhosis (2025)

Insilico Medicine featured in Harvard Business School case on Rentosertib

[Press-News.org] UMass Amherst researchers reveal mechanism of novel biological electron transferResearchers at UMass Amherst led by microbiologist Derek Lovley have identified key components that make hair-like pili called nanowires in certain bacteria able to conduct electricity and show their importance in biological electron transport